The Empire Strikes Back 99 - The Death of Empress Veronica

The Death is Announced

January 22, 1901, a messenger arrives to a hastily-assembled Senate.

Senators, I bring sad news. Empress Victoria has passed away this evening, after failing health throughout January. Her funeral will be on the 25th. Her wish was for it to be of military style, and white instead of black, and so it shall be. Afterward, Prince Alvértos will make an address to the Senate.

The Senators Respond

The Palaiologoi is in shock at the death of Empress Veronica. Also, I am saddened to inform you of the passing of Ambrosio Palaiologos. A faithful senator to the very end, he was killed by assassins at his home. Either that, or someone accidently tossed a torch on his house. And then went in and stabbed him. We are currently deciding the next head of the family as his lone child has renounced the material world and has become the Patriarch’s Chief Assistant in Antioch.

Sincerely, Spokesman Christophoros Palaiologos

I send my condolences to the royal family. Empress Veronica’s reign defined an era and led this empire to such heights that will surely be difficult to surpass.

- Senator Leonardo Favero

“The Veronikan Era has passed and with it, the Basilissa of my father and grandfather. The Angeloi offer their deepest sympathies to the throne.”

- Senator Alexios Angelos

Though my supports and I have clashed with elements of Her Imperial Majesty’s government we have always had great affection and loyalty to our dear departed Empress.

Our thoughts are with the Imperial Family at this time.

- Senator Gray

((Private))

Michael read the newspaper. “EMPRESS VERONICA DEAD,” the headlines read.

He was sad, of course, but he was also angry. He knew the truth, as Minister of Security. The Blachernae Gazette didn’t tell the whole truth. But the truth was out there.Soon after the Empress’s death, an emergency meeting of the Ministry of Security was called, and some of the members of the General Staff were in attendance, including Strategos Dalassenos, as well as some doctors from the Pandidakterion. The autopsy on the Empress had shown that she had been drained of her blood, with two puncture holes on her neck. The doctors were baffled and at a loss to explain how she lost so much blood. She was old, but she wasn’t expected to die like this! The General Staff and the Secret Police agreed to a measure to hunt down the supposed killer, while hiding the truth from the public. The citizens weren’t ready for the truth. Michael knew they would not find their killer, whom they assumed to be human. Michael and Ioannes knew what really happened that night. IT got to her. IT killed her. IT was punishing them.

He threw the newspaper at the wall, hitting his father’s portrait. “NOOOOOOOO!!!!!!!!” he screamed. “I WILL FIND YOU AND HUNT YOU DOWN WITH EVERYTHING AT MY DISPOSAL! MARK MY WORDS, DRACULA, YOU WILL NOT LIVE TO SEE THE CORONATION OF THE EMPEROR!”

((Public))

I humbly offer my deepest condolences to the royal family. The Empire reached its greatest extent in civilization and power under her reign, a true Pax Romana. Whether the empress caused the period, or the period creates the empress, she fitted her time perfectly. She will be greatly missed by all of the citizens of Rome. Long live the new Emperor!

- Michael Doukas

((Private again))

Dr. Stavridis’s DiaryFor a while sheer anger mastered me. It was as if he had during her life struck Loukia on the face. I smote the table hard and rose up as I said to him, “Dr. von Habsburg, are you mad?”

He raised his head and looked at me, and somehow the tenderness of his face calmed me at once. “Vould ich vere!” he said. “Madness vere easy zo bear kompared vith zruth like zhis. Oh, mein freund, vhy, zhink du, did ich go so far round, vhy take so long to tell so simple a zhing? Vas it because ich hate du und have hated du all mein life? Was it because ich vished to give du pain? Vas it zhat ich wanted, no so late, revenge for zhat time vhen you saved my life, and from a fearful death? Ah nein!”

“Forgive me,” said I.

He went on (and I’ll just stop representing his accent here, it’s tiring), “My friend, it was because I wished to be gentle in the breaking to you, for I know you have loved that so sweet lady. But even yet I do not expect you to believe. It is so hard to accept at once any abstract truth, that we may doubt such to be possible when we have always believed the ‘no’ of it. It is more hard still to accept so sad a concrete truth, and of such a one as Frau Loukia. Tonight I go to prove it. Dare you come with me?”

This staggered me. A man does not like to prove such a truth, Kyrillos excepted from the category, jealousy.

“And prove the very truth he most abhorred.”

He saw my hesitation, and spoke, “The logic is simple, no madman’s logic this time, jumping from tussock to tussock in a misty bog. If it not be true, then proof will be relief. At worst it will not harm. If it be true! Ah, there is the dread. Yet every dread should help my cause, for in it is some need of belief. Come, I tell you what I propose. First, that we go off now and see that child in the hospital. Dr. Melissenos, of the North Hospital, where the papers say the child is, is a friend of mine, and I think of yours since you were in class at Vienna. He will let two scientists see his case, if he will not let two friends. We shall tell him nothing, but only that we wish to learn. And then . . .”

“And then?”

He took a key from his pocket and held it up. “And then we spend the night, you and I, in the churchyard where Loukia lies. This is the key that lock the tomb. I had it from the coffin man to give to Michael.”

My heart sank within me, for I felt that there was some fearful ordeal before us. I could do nothing, however, so I plucked up what heart I could and said that we had better hasten, as the afternoon was passing.

We found the child awake. It had had a sleep and taken some food, and altogether was going on well. Dr, Melissenos took the bandage from its throat, and showed us the punctures. There was no mistaking the similarity to those which had been on Loukia’s throat. They were smaller, and the edges looked fresher, that was all. We asked Melissenos to what he attributed them, and he replied that it must have been a bite of some animal, perhaps a rat, but for his own part, he was inclined to think it was one of the bats which are so numerous on the northern heights of Constantinople. “Out of so many harmless ones,” he said, “there may be some wild specimen from the South of a more malignant species. These things do occur, you, know. Only ten days ago a wolf got out, and was, I believe, traced up in this direction. For a week after, the children were playing nothing but Red Riding Hood on the Heath and in every alley in the place until this ‘bloofer lady’ scare came along, since then it has been quite a gala time with them. Even this poor little mite, when he woke up today, asked the nurse if he might go away. When she asked him why he wanted to go, he said he wanted to play with the ‘bloofer lady’.”

“I hope,” said von Habsburg, “that when you are sending the child home you will caution its parents to keep strict watch over it. These fancies to stray are most dangerous, and if the child were to remain out another night, it would probably be fatal. But in any case I suppose you will not let it away for some days?”

“Certainly not, not for a week at least, longer if the wound is not healed.”

Our visit to the hospital took more time than we had reckoned on, and the sun had dipped before we came out. When Van Helsing saw how dark it was, he said,

“There is not hurry. It is more late than I thought. Come, let us seek somewhere that we may eat, and then we shall go on our way.”

About ten o’clock we started from the inn. It was then very dark, and the scattered lamps made the darkness greater when we were once outside their individual radius. The Professor had evidently noted the road we were to go, for he went on unhesitatingly, but, as for me, I was in quite a mixup as to locality. As we went further, we met fewer and fewer people, till at last we were somewhat surprised when we met even the patrol of horse police going their usual suburban round. At last we reached the wall of the churchyard, which we climbed over. With some little difficulty, for it was very dark, and the whole place seemed so strange to us, we found the Este-Ravenna tomb. The Professor took the key, opened the creaky door, and standing back, politely, but quite unconsciously, motioned me to precede him.Von Habsburg went about his work systematically. Holding his candle so that he could read the coffin plates, and so holding it that the sperm dropped in white patches which congealed as they touched the metal, he made assurance of Loukia’s coffin. Another search in his bag, and he took out a turnscrew.

“What are you going to do?” I asked.

“To open the coffin. You shall yet be convinced.”

He opened the coffin and motioned to me to look.

I drew near and looked. The coffin was empty. It was certainly a surprise to me, and gave me a considerable shock, but Von Habsburg was unmoved. He was now more sure than ever of his ground, and so emboldened to proceed in his task. “Are you satisfied now, friend John?” he asked.

I felt all the dogged argumentativeness of my nature awake within me as I answered him, “I am satisfied that Loukia’s body is not in that coffin, but that only proves one thing.”

“And what is that, friend John?”

“That it is not there.”

“That is good logic,” he said, “so far as it goes. But how do you, how can you, account for it not being there?”

“Perhaps a body-snatcher,” I suggested. “Some of the undertaker’s people may have stolen it.” I felt that I was speaking folly, and yet it was the only real cause which I could suggest.

The Professor sighed. “Ah well!” he said,” we must have more proof. Come with me.”

He put on the coffin lid again, gathered up all his things and placed them in the bag, blew out the light, and placed the candle also in the bag. We opened the door, and went out. Behind us he closed the door and locked it. He handed me the key, saying, “Will you keep it? You had better be assured.”

I laughed, it was not a very cheerful laugh, I am bound to say, as I motioned him to keep it. “A key is nothing,” I said, “there are many duplicates, and anyhow it is not difficult to pick a lock of this kind.”

He said nothing, but put the key in his pocket. Then he told me to watch at one side of the churchyard whilst he would watch at the other.

I took up my place behind a yew tree.Suddenly, as I turned round, I thought I saw something like a white streak, moving between two dark yew trees at the side of the churchyard farthest from the tomb. At the same time a dark mass moved from the Professor’s side of the ground, and hurriedly went towards it. Then I too moved, but I had to go round headstones and railed-off tombs, and I stumbled over graves. The sky was overcast, and somewhere far off an early cock crew. A little ways off, beyond a line of scattered juniper trees, which marked the pathway to the church, a white dim figure flitted in the direction of the tomb. The tomb itself was hidden by trees, and I could not see where the figure had disappeared. I heard the rustle of actual movement where I had first seen the white figure, and coming over, found the Professor holding in his arms a tiny child. When he saw me he held it out to me, and said, “Are you satisfied now?”

“No,” I said, in a way that I felt was aggressive.

“Do you not see the child?”

“Yes, it is a child, but who brought it here? And is it wounded?”

“We shall see,”said the Professor, and with one impulse we took our way out of the churchyard, he carrying the sleeping child.

When we had got some little distance away, we went into a clump of trees, and struck a match, and looked at the child’s throat. It was without a scratch or scar of any kind.

“Was I right?” I asked triumphantly.

“We were just in time,” said the Professor thankfully.

We had now to decide what we were to do with the child, and so consulted about it. If we were to take it to a police station we should have to give some account of our movements during the night. At least, we should have had to make some statement as to how we had come to find the child. So finally we decided that we would take it to the Heath, and when we heard a policeman coming, would leave it where he could not fail to find it. We would then seek our way home as quickly as we could. All fell out well. At the edge of the Heath we heard a policeman’s heavy tramp, and laying the child on the pathway, we waited and watched until he saw it as he flashed his lantern to and fro. We heard his exclamation of astonishment, and then we went away silently. By good chance we got a cab near the ‘Spainiards,’ and drove to town.

I cannot sleep, so I make this entry. But I must try to get a few hours’ sleep, as Von Habsburg is to call for me at noon. He insists that I go with him on another expedition.27 September. 1901

It was two o’clock, several months after the funeral of the Empress, before we found a suitable opportunity for our attempt. The funeral held at noon was all completed, and the last stragglers of the mourners had taken themselves lazily away, when, looking carefully from behind a clump of alder trees, we saw the sexton lock the gate after him. We knew that we were safe till morning did we desire it, but the Professor told me that we should not want more than an hour at most. I shrugged my shoulders, however, and rested silent, for von Habsburg had a way of going on his own road, no matter who remonstrated. He took the key, opened the vault, and again courteously motioned me to precede. Von Habsburg walked over to Loukia’s coffin, and I followed. He bent over and again forced back the leaden flange, and a shock of surprise and dismay shot through me.

There lay Loukia, seemingly just as we had seen her the night before her funeral. She was, if possible, more radiantly beautiful than ever, and I could not believe that she was dead. The lips were red, nay redder than before, and on the cheeks was a delicate bloom.

“Is this a juggle?” I said to him.

“Are you convinced now?” said the Professor, in response, and as he spoke he put over his hand, and in a way that made me shudder, pulled back the dead lips and showed the white teeth. “See,” he went on,”they are even sharper than before. With this and this,” and he touched one of the canine teeth and that below it, “the little children can be bitten. Are you of belief now, friend John?”

Once more argumentative hostility woke within me. I could not accept such an overwhelming idea as he suggested. So, with an attempt to argue of which I was even at the moment ashamed, I said, “I want to believe, but she may have been placed here since last night.”

“Indeed? That is so, and by whom?”

“I do not know. Someone has done it.”

“And yet she has been dead one week. Most peoples in that time would not look so.”

I had no answer for this, so was silent. Von Habsburg did not seem to notice my silence. He said to me,

“Here, there is one thing which is different from all recorded. Here is some dual life that is not as the common. She was bitten by the vampire when she was in a trance, sleep-walking, oh, you start. You do not know that, friend John, but you shall know it later, and in trance could he best come to take more blood. In trance she dies, and in trance she is Un-Dead, too. So it is that she differ from all other. Usually when the Un-Dead sleep at home,” as he spoke he made a comprehensive sweep of his arm to designate what to a vampire was ‘home’, “their face show what they are, but this so sweet that was when she not Un-Dead she go back to the nothings of the common dead. There is no malign there, see, and so it make hard that I must kill her in her sleep.”

This turned my blood cold, and it began to dawn upon me that I was accepting von Habsburg’s theories. But if she were really dead, what was there of terror in the idea of killing her?

He looked up at me, and evidently saw the change in my face, for he said almost joyously, “Ah, you believe now?”

I answered, “Do not press me too hard all at once. I am willing to accept. How will you do this bloody work?”

“I shall cut off her head and fill her mouth with garlic, and I shall drive a stake through her body.”

It made me shudder to think of so mutilating the body of the woman whom I had loved. And yet the feeling was not so strong as I had expected. I was, in fact, beginning to shudder at the presence of this being, this Un-Dead, as Von Habsburg called it, and to loathe it. Is it possible that love is all subjective, or all objective?

I waited a considerable time for Von Habsburg to begin, but he stood as if wrapped in thought. Presently he closed the catch of his bag with a snap, and said,

“ She have yet no life taken, though that is of time, and to act now would be to take danger from her forever. But then we may have to want Michael, and how shall we tell him of this? If you, who saw the wounds on Loukia’s throat, and saw the wounds so similar on the child’s at the hospital, if you, who saw the coffin empty last night and full today with a woman who have not change only to be more rose and more beautiful in a whole week, after she die, if you know of this and know of the white figure last night that brought the child to the churchyard, and yet of your own senses you did not believe, how then, can I expect Michael, who know none of those things, to believe?

“My mind is made up. Let us go. You return home for tonight to your asylum, and see that all be well. As for me, I shall spend the night here in this churchyard in my own way. Tomorrow night you will come to me to the Hotel at ten of the clock. I shall send for Michael to come too, and also that so fine young man of Oceania that gave his blood. Later we shall all have work to do. I come with you so far as Hippodrome District and there dine, for I must be back here before the sun set.”

So we locked the tomb and came away, and got over the wall of the churchyard, which was not much of a task, and drove back to Hippodrome District.Note left by von Habsburg in his portmanteau, [REDACTED] directed to John Stavridis, M. D. (not delivered)

27 September

Friend John,

I write this in case anything should happen. I go alone to watch over the churchyard. The Un-Dead may be there, waiting for us. I shall place garlic and crucifixes around the tomb to limit the Un-Dead’s movement. But the Un-Dead are strong, and if I fail, you must be prepared to take up the challenge.

Therefore I write this in case . . . Take the papers that are with this, the diaries of Dalassenos and the rest, and read them, and then find this great Un-Dead, and cut off his head and burn his heart or drive a stake through it, so that the world may rest from him.

If it be so, farewell.

VON HABSBURG.

Dr. Stavridis’s Diary

29 September.

Last night, at a little before ten o’clock, Michael and Markos Quintus came into von Habsburg’s room. He told us all what he wanted us to do, but especially addressing himself to Michael, as if all our wills were centered in his. He began by saying that he hoped we would all come with him too, “for,” he said, “there is a grave duty to be done there. You were doubtless surprised at my letter?” This query was directly addressed to Senator Doukas. “I was. It rather upset me for a bit. There has been so much trouble around my house of late that I could do without any more. I have been curious, too, as to what you mean.

“Markos and I talked it over, but the more we talked, the more puzzled we got, till now I can say for myself that I’m about up a tree as to any meaning about anything.”

“Me too,” said Markos Quintus laconically.

“Oh,” said the Professor, “then you are nearer the beginning, both of you, than friend John here, who has to go a long way back before he can even get so far as to begin.”

It was evident that he recognized my return to my old doubting frame of mind without my saying a word. Then, turning to the other two, he said with intense gravity,

“I want your permission to do what I think good this night. It is, I know, much to ask, and when you know what it is I propose to do you will know, and only then how much. Therefore may I ask that you promise me in the dark, so that afterwards, though you may be angry with me for a time, I must not disguise from myself the possibility that such may be, you shall not blame yourselves for anything.”

“That’s frank anyhow,” broke in Markos. “I’ll answer for the Professor. I don’t quite see his drift, but I swear he’s honest, and that’s good enough for me.”

“I thank you, Sir,” said Von Habsburg proudly. “I have done myself the honor of counting you one trusting friend, and such endorsement is dear to me.” He held out a hand, which Markos took.

Then Michael spoke out, “Dr. Von Habsburg, I don’t quite like to ‘buy a pig in a poke’, as they say in Caledonia, and if it be anything in which my honour as a gentleman or my faith as a Christian and a servant of the Empire is concerned, I cannot make such a promise. If you can assure me that what you intend does not violate either of these two, then I give my consent at once, though for the life of me, I cannot understand what you are driving at.”

“I accept your limitation,” said Von Habsburg.“Agreed!” said Michael. “That is only fair. And now that the pourparlers are over, may I ask what it is we are to do?”

“I want you to come with me, and to come in secret, to the churchyard at Kingstead.”

Michael’s face fell as he said in an amazed sort of way,

“Where poor Loukia is buried?”

The Professor bowed.

Michael went on, “And when there?”

“To enter the tomb!”

Michael stood up. “Professor, are you in earnest, or is it some monstrous joke? Pardon me, I see that you are in earnest.” He sat down again, but I could see that he sat firmly and proudly, as one who is on his dignity. There was silence until he asked again, “And when in the tomb?”

“To open the coffin.”

“This is too much!” he said, angrily rising again. “I am willing to be patient in all things that are reasonable, but in this, this desecration of the grave, of one who . . .” He fairly choked with indignation. “Would it not be well to hear what I have to say?” said Van Helsing. “And then you will at least know the limit of my purpose. Shall I go on?”

“That’s fair enough,” broke in Quintus.

After a pause Von Habsburg went on, evidently with an effort, “Miss Loukia is dead, is it not so? Yes! Then there can be no wrong to her. But if she be not dead. . .”

Michael jumped to his feet, “Good God!” he cried. “What do you mean? Has there been any mistake, has she been buried alive?”He groaned in anguish that not even hope could soften.

“I did not say she was alive, my child. I did not think it. I go no further than to say that she might be Un-Dead.”

“Un-Dead! Not alive! What do you mean? Is this all a nightmare, or what is it?”

“There are mysteries which men can only guess at, which age by age they may solve only in part. Believe me, we are now on the verge of one. But I have not done. May I cut off the head of dead Miss Loukia?”Michael screamed.

“Heavens and earth, no!” cried Michael in a storm of passion. “WHY, Habsburg, WHY should I help you carry out this act of desecration?! You know I have other things to do, such as find the empress’s killer!”

Von Habsburg rose up from where he had all the time been seated, and said, gravely and sternly, “My Lord Doukas, I too, have a duty to do, a duty to others, a duty to you, a duty to the dead, and by God, I shall do it! All I ask you now is that you come with me, that you look and listen, and if when later I make the same request you do not be more eager for its fulfillment even than I am, then, I shall do my duty, whatever it may seem to me. And then, to follow your Lordship’s wishes I shall hold myself at your disposal to render an account to you, when and where you will.” His voice broke a little, and he went on with a voice full of pity.

“But I beseech you, do not go forth in anger with me. In a long life of acts which were often not pleasant to do, and which sometimes did wring my heart, I have never had so heavy a task as now. Believe me that if the time comes for you to change your mind towards me, one look from you will wipe away all this so sad hour, for I would do what a man can to save you from sorrow. Just think. For why should I give myself so much labor and so much of sorrow? I have come here from my own land to do what I can of good, at the first to please my friend John, and then to help a sweet young lady, whom too, I come to love. For her, I am ashamed to say so much, but I say it in kindness, I gave what you gave, the blood of my veins. I gave it, I who was not, like you, her lover, but only her physician and her friend. I gave her my nights and days, before death, after death, and if my death can do her good even now, when she is the dead Un-Dead, she shall have it freely.” He said this with a very grave, sweet pride, and Michael was much affected by it.

He took the old man’s hand and said in a broken voice, “Oh, it is hard to think of it, and I cannot understand, but at least I shall go with you and wait.”

The Funeral of Empress Veronica

And so passed Empress Veronica. She had been the last survivor of the mysterious events in the old Imperial Palace that had unfolded after Andronikos had been made heir in 1820. When she came to the throne in 1836, she masterfully brought the newly reformed Senate under her control, took up the reigns of the Empire, and brought prosperity back to the Empire. During her sixty-five year reign, the Empire industrialized, became far more educated, and expanded (primarily in Africa). She would be remembered as one of the greatest rulers of the Roman Empire.

Her funeral was a sorrowful affair, with the whole Imperial family, the Senate, and crowds of mourners attending. She was laid to rest in a new mausoleum within the Blachernae Palace complex, one that extended under the Theodosian walls. After the ceremony was over, the Imperial family remained for their own remembrances.

Meanwhile, the Senate gathered at the Grand Palace complex in the heart of Constantinople, waiting for Emperor Alvértos to arrive and give the first address of his reign to the Senate.

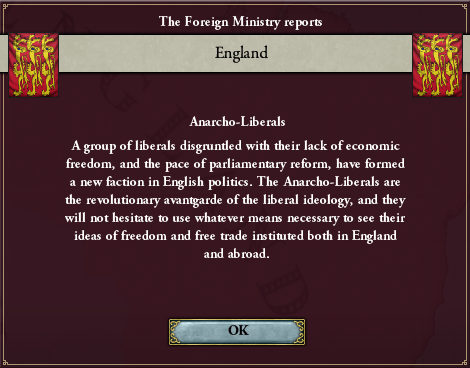

The State of the Empire

Senators,

Thank you for your many kind words regarding Our mother. We have decided to continue the methods of governance she developed. The same ministries will be appointed, all current Senators retain their appointments to the Senate, the governorships will continue.

The archivists found several newspapers to be worthy of archiving, and We have had copied made for you all.

As well, the Senate’s map shall be updated.

Let us describe the royal family, as Our mother did not share specifics of her grandchildren with you. We have been happily married to Alexandria of Scandinavia since 1863, and have had six children. Alvértos Nikephoros was born in 1864, but died in 1892 of influenza. Konstantios was born in 1865, and in 1893 married Princess Veronica Maria of Denmark. They have four children. Louiza was born in 1867, and in 1889 married Alexander William George Duff, 1st Duke of Fife. They had three children. The first, a son, was stillborn, but the two daughters born later are in good health. Veronica was born in 1868, and is yet unmarried. Mathilde was born in 1869, and in 1896 married Prince Carl of Scandinavia. They have not had any children so far. Finally, Alexander was born in 1871, but died a day later.

The last announcement before We share the address Our mother had begun planning is that We will take the name of Konstantinos XX on Our coronation. And now, the State of the Empire since 1900, as prepared by Empress Veronica.

At the very beginning of 1900, We received several requests for alliances. Those from Dai Nam, Siam, Benin, and Baluchistan were accepted, as We believed these alliances would allow Us to influence these regions for the better. An alliance with England was rejected as We felt their expansion in South America was disrupting the balance of power. Instead, an alliance with the United Tribes of America was signed.

Meanwhile, Scandinavia declared that Greenland was rightfully theirs, and declared war on Scotland for it.

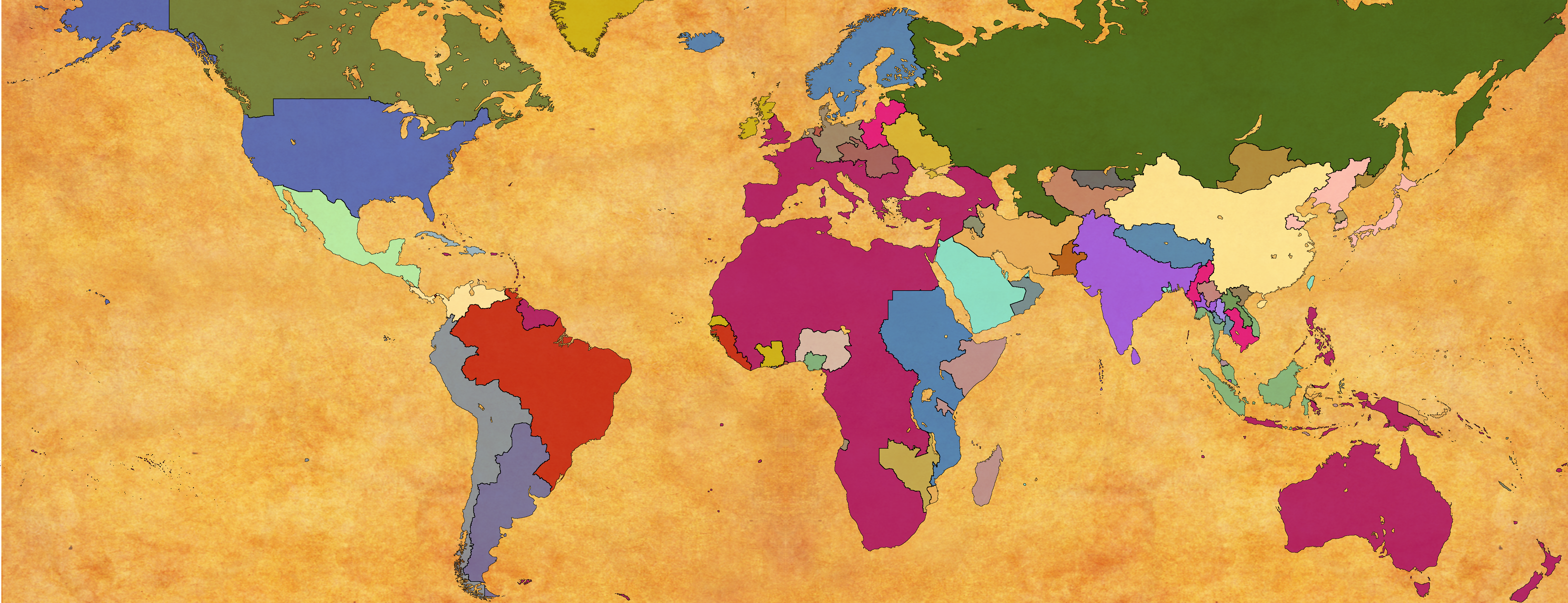

In March, We received news from Our expedition to the North Pole: they had been the first to make it.

Shortly thereafter, the Olympic Committee invited Us to send a team to the second Olympics. We promptly agreed.

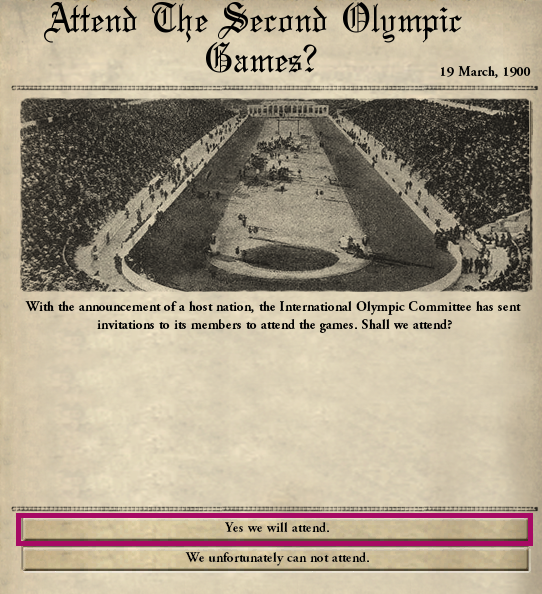

In England, there was stranger news. A new political force had coalesced around complete economic freedom. Their ideas soon spread to the Empire.

While there had been minor clashes with rebel groups throughout the year, in June We saw something new: a rising of people who wanted more independence for New Zealand.

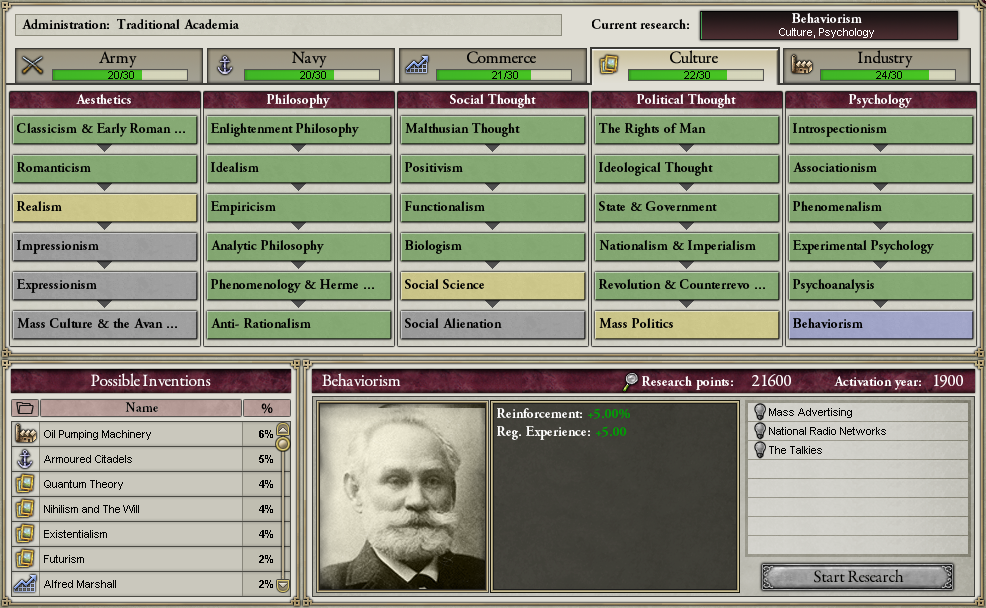

As the core ideas of anti-rationalism formed, We asked the Psychology department to apply these insights to their field.

In October, when Scandinavia had fully committed to their war, Germany declared war on them in order to reclaim the Sjaelland islands.

In late December, Jacobin rebels rose yet again.

Unfortunately, Empress Veronica’s planned address ended on that note. We do not know what more could be added, though. Do the Senators have any questions or comments?

Senators' Replies

These Anarcho-Liberals look like trouble, but they can be managed like the militant socialists and the Jacobins, and if they are willing to work with us I would gladly do so. I send my deepest condolences to the people of Napoli, who have suffered greatly from the volcanic eruption.

First to the North Pole! A triumph for the Empire! Now to the South Pole!

I am looking forward to the coronation. Long live the Emperor!- Michael Doukas

((Private))

“Ha, I have won!” said Konstantinos, standing in front of him.

If you ignore him he’ll go away, thought Michael.

“Do you really think I would go away that easily?” said Konstantinos. “Wrong! And now the Emperor is adopting my name…”

Michael slammed his fist down on the table. When he looked up again, Konstantinos was gone.

“My apologies,” he said to the other senators.

Damn how much “economic freedom” do these capitalists need!

- Senator Gray

“Greetings fellow senators, I am here for two reasons this day. First to give my condolences to both the Royal and the Palaiologos family, Both of your families have truly lost someone of great importance to not only the people they knew, but to the Empire itself. Secondly, I am announcing my retirement from both my governorship and my role as minister of armaments. I sincerely hope these offices are filled by good, hard-working Romans. And lastly, as requested by many members of my house, me and my kin are no longer Kvensson’s, but as members of house Varangios. God bless the Empire and the new Emperor.”

-Senator Magnus Kvensson

First Attempt at Postings

Thank you, Senators. We plan to keep the current appointments for the next five years. They would be thus:

Ministers:

Foreign minister - Senator Favero

Armament minister -

Minister of security - Senator Doukas

Chief of Staff - Senator Στήβεν

Chief of the Army - Senator Theodosio

Chief of the Navy - Senator Smithereens

Governors:

(North) Africa - Senator Damaskinos

Britannia - Senator Palaiologos

Dalmatia - Heraclius Komnenos

Macedonia - Senator Angelos

Naples - Senator Septiadis

Palestine - Senator Doukas

Raetia - Senator Comminus

Sicily - Senator Smithereens

Thracia - Prince Alvértos

Brittany - Senator Γκρέυ

Italy - Senator Favero

Philippines - Senator Nguyen-Climaco

Spain - Senator Theodosio

And remember that Australia includes New Zealand, the eastern half of New Guinea, and the smaller islands eastwards of there. The Philippines include Java, the western half of New Guinea, and the islands between those three points.

The following provinces will be placed in the control of non-Senator governors:

Armenia

Asia

Australia

Egypt

Georgia

Guayana

Mauretania

Syria

Aquitaine

Azerbaijan

Burgundy

Catalonia

France

Belgium

Java

New Zealand

South Africa

Wales

Are there any desired changes? And would any Senators volunteer to be the new Armaments Minister?

Senators' Replies

We have selected a new head of the Palaiologoi Family, I, Christophoros Palaiologos, has been selected. I vow to make the Eastern Roman Empire great and strong! We will conquer our way to victory with our Greek citizens! ((basically a proto- fascist from seeing so many of his family killed)).

- Senator Christophoros Palaiologos, duke of Nicaea

I urge you to choose your words carefully, sir, lest you be called a traitor and supporter of the Konstantinians and Markos Angelos. For those very words you said echo those that my brother proclaimed during his rebellion. Don’t go down the path he did. It will not end well for you. I am saying this for your own good.

- Doukas

Alexios Angelos asks, “Isn’t our empire already great and strong? Suggesting otherwise seems foolish.”

Bah! Fools, every single one of you! Konstantinos did not know what was great for the country, just what was great for him! Do you see the Russians amassing armies at our borders? Do you see the minorities attempting to commit acts of treason against the government? We must arm and prepare for the eventual betrayal!

- Senator Christophoros Palaiologos

Closing the Session

Again, thank you, Senators. Senator Palaiologos, though your rhetoric is more inflamed than We would use, your passion is good. Therefore We are assigning you as armaments minister. Therefore the final appointments are:

Ministers:

Foreign minister - Senator Favero

Armament minister - Senator Palaiologos

Minister of security - Senator Doukas

Chief of Staff - Senator Στήβεν

Chief of the Army - Senator Theodosio

Chief of the Navy - Senator Smithereens

Governors:

(North) Africa - Senator Damaskinos

Britannia - Senator Palaiologos

Dalmatia - Heraclius Komnenos

Macedonia - Senator Angelos

Naples - Senator Septiadis

Palestine - Senator Doukas

Raetia - Senator Comminus

Sicily - Senator Smithereens

Thracia - Prince Alvértos

Brittany - Senator Γκρέυ

Italy - Senator Favero

Philippines - Senator Nguyen-Climaco

Spain - Senator Theodosio

And remember that Australia includes New Zealand, the eastern half of New Guinea, and the smaller islands eastwards of there. The Philippines include Java, the western half of New Guinea, and the islands between those three points.

The following provinces will be placed in the control of non-Senator governors:

Armenia

Asia

Australia

Egypt

Georgia

Guayana

Mauretania

Syria

Aquitaine

Azerbaijan

Burgundy

Catalonia

France

Belgium

Java

New Zealand

South Africa

Wales

As always, Senators, thank you for your time.

After the Address

Very good, armaments minister! I will be sure to preside over the glorious expansion of our military as armaments minister! I promise this! The military will grow strong under my direction! My rhetoric is designed to tell the Greek people the truth and only the truth. We must have a square deal for the worker for each worker’s capability! We must destroy the forces of reactionism, socialism, communism, and liberalism that bring this country down.

I claim the mantle of leadership of the Kyriarchia! Together, the Greeks and the Eastern Roman Empire will stand strong against the world!

- Senator Palaiologos

“Eastern Roman, senator? Most of Europe bows to our new Basileus, so let us not reuse titles that have been obsolete for many centuries.”

- Senator Angelos

Yes, I dare say Eastern Roman because this country is not yet at the peak of its power! We need war to truly become the new Roman Empire! Rome only became Rome because of their martial prowess! We are not truly Rome until we show our martial prowess!

- Senator Palaiologos

Leonardo Favero, long-time senator and foreign minister, was found dead in his estate outside Venice, having received several stabs to the torso. There are clear signs that someone rifled through the files in his office. As the former minister of intelligence and current foreign minister, it is possible that the senator possessed sensitive documents, some worth killing for. Local authorities suspect the culprit may be working for either the Russians, communists, socialists, anarchists, reactionaries, cultists, or some unknown party. In short, they have no idea who did it. The family will be holding a small funeral for relatives only. His son, Raphael, will be taking his place in the senate.

I have told the Senate, Rome is beset on all sides my enemies! We must capture those responsible for a senator’s death and torture them for information! Then we will hang them! We need a stronger military and better security forces to make sure this never happens again!

- Senator Palaiologos

No, please stay out of this. This is the job of the Ministry of Security. I personally knew Leonardo, and I know of subversive elements (NOT minorities but Greeks, mind you) who would very much like him dead. Therefore, as Minister of Security I strongly urge you to keep to yourself and not try to interfere in our investigation. And it is not our way to torture and kill people for information; that would play into the hands of the communists.

- Senator Doukas

A job you are not doing! If someone commits crime, we will punish them. However, I know that minorities are a far greater threat to the stability of the Empire than the Greeks.

We must do what is right and best for the country, not what is not against your morals. The decadence and aristocratic, useless morals of the upper class is unbearable!

- Senator Palaiologos

I assure you, I am doing my job to the best of my ability! Who are you to question my performance? Only the Emperor can do that! And if somebody commits a crime, we punish them, of course, but we do not torture people and we certainly do not kill people without reason!

- Senator Doukas

I dare to question the performance of anyone not performing up to expectations which include you! This is the problem with the nobility! They have no skill yet demand all the power! We need a meritocratic, Greek administration for this great Empire!

We will torture people for the greater good of the country, your morals cannot get in the way of security! I will not kill people without reason, some criminals should be killed but others should not.

- Senator Palaiologos

I have my credentials. I have served a number of years with the imperial legions. When Konstantinos rebelled all those years ago, I was the one who defeated him. I was the one who put down Markos Angelos’s many rebellions and have been hunting him down for the last several years. I organized the secret police and made it into an instrument of justice, placing safeguards on it to prevent its abuse and corruption into a weapon of tyranny. Torture would be used as a propaganda tool by our enemies whom you say are all barbarians. They would claim that “why does the Armaments Minister claim that Rome is the center of civilization when it treats its own people in barbaric ways?” How would you respond to that? And our current interrogation methods are effective enough. Every single suspect we have interrogated, including servants of Markos Angelos, have cooperated with us and have been providing valuable information on rebel activities.

Do you have anything to say to our non-Greek senators in attendance, to remind them of what happened when Konstantinos stormed into this palace during his rebellion and shot the Hispanian senator Theodosio in cold blood? When he ordered the purging of all non-Greeks to “make Rome great again?” What say you to them, whose families were gunned down by Konstantinos’s mobs and soldiers ruthlessly? What say you to the non-Greek but Roman citizens who through Romanitas have been loyal citizens of the Empire and have never harbored thoughts of treason? Answer me!

- Senator Doukas

Bah! All you know are aristocratic notions of morality, class, and more! You put down a few rebellions? How many troops did you have? 60,000 against 3,000 rebels? Anyways, that is just tactical experience. Maybe we should make you a colonel and send you to the border with Germany! Secret police? Do not forget the instrumental role of the former Empress Veronica and the Senate in the formation of the secret police! Why should we make torture known to the world? Do we publicize our military and industrial secrets? Why would we publicize our use of torture? Our enemies are barbarians, they themselves use torture! They would appear hypocritical to accuse us of torture, they would not dare to do that. I do not say we ought to oppress minorities. Many are criminals but some, I agree, are good people. We should treat them as valuable members of this Empire, but not as valuable as the great Greek citizens that are the core of this glorious empire. Theodosio is more Greek than Hispanian! He is a good citizen of the empire! Purging all non- Greeks is a mistake as is his reactionary, aristocratic policies. Konstantinos should be tortured and hanged for his crimes! However, someone is unable to successfully shake him off. I will not name names but everyone knows who it is!

Do you forget when the Germanic tribes sacked Rome? Do you forget when the tribes in Scotland attacked Britannia and looted their way through it? Do you know what people from non- Roman countries are bringing in when they come here?

We will never forget nor forgive!

- Senator Palaiologos

My fellow Senators I request a leave of absence, my old bones grow tired and it is time another take my place.

I will return to my governors residence and consult the people.

- Former Senator Gray

((Private))

Dr. Stavridis’s Diary

It was just a quarter before twelve o’clock when we got into the churchyard over the low wall. The night was dark with occasional gleams of moonlight between the dents of the heavy clouds that scudded across the sky. We all kept somehow close together, with Von Habsburg slightly in front as he led the way. When we had come close to the tomb I looked well at Michael, for I feared the proximity to a place laden with so sorrowful a memory would upset him, but he bore himself well. I took it that the very mystery of the proceeding was in some way a counteractant to his grief. The Professor unlocked the door, and seeing a natural hesitation amongst us for various reasons, solved the difficulty by entering first himself. The rest of us followed, and he closed the door. He then lit a dark lantern and pointed to a coffin. Michael stepped forward hesitatingly. Von Habsburg said to me, “You were with me here yesterday. Was the body of Frau Loukia in that coffin?”

“It was.”

The Professor turned to the rest saying, “You hear, and yet there is no one who does not believe with me.’

He took his screwdriver and again took off the lid of the coffin. Michael looked on, very pale but silent. When the lid was removed he stepped forward. He evidently did not know that there was a leaden coffin, or at any rate, had not thought of it. When he saw the rent in the lead, the blood rushed to his face for an instant, but as quickly fell away again, so that he remained of a ghastly whiteness. He was still silent. Von Habsburg forced back the leaden flange, and we all looked in and recoiled.

The coffin was empty!

For several minutes no one spoke a word. The silence was broken by Markos Quintus, “Professor, I answered for you. Your word is all I want. I wouldn’t ask such a thing ordinarily, I wouldn’t so dishonor you as to imply a doubt, but this is a mystery that goes beyond any honor or dishonor. Is this your doing?”

“I swear to you by all that I hold sacred that I have not removed or touched her. What happened was this. Two nights ago my friend Stavridis and I came here, with good purpose, believe me. I opened that coffin, which was then sealed up, and we found it as now, empty. We then waited, and saw something white come through the trees. The next day we came here in daytime and she lay there. Did she not, friend John?

“Yes.”

“That night we were just in time. One more so small child was missing, and we find it, thank God, unharmed amongst the graves. Yesterday I came here before sundown, for at sundown the Un-Dead can move. I waited here all night till the sun rose, but I saw nothing. It was most probable that it was because I had laid over the clamps of those doors garlic, which the Un-Dead cannot bear, and other things which they shun. Last night there was no exodus, so tonight before the sundown I took away my garlic and other things. And so it is we find this coffin empty. But bear with me. So far there is much that is strange. Wait you with me outside, unseen and unheard, and things much stranger are yet to be. So,” here he shut the dark slide of his lantern, “now to the outside.” He opened the door, and we filed out, he coming last and locking the door behind him.

Von Habsburg took from his bag a mass of what looked like thin, wafer-like biscuit, which was carefully rolled up in a white napkin. Next he took out a double handful of some whitish stuff, like dough or putty. He crumbled the wafer up fine and worked it into the mass between his hands. This he then took, and rolling it into thin strips, began to lay them into the crevices between the door and its setting in the tomb. I was somewhat puzzled at this, and being close, asked him what it was that he was doing. Arthur and Quincey drew near also, as they too were curious.

He answered, “I am closing the tomb so that the Un-Dead may not enter.”

“And is that stuff you have there going to do it?”

“It Is.”

“What is that which you are using?” This time the question was by Michael. Von Habsburg reverently lifted his hat as he answered.

“The Host. I brought it from Vienna.”

It was an answer that appalled the most sceptical of us, and we felt individually that in the presence of such earnest purpose as the Professor’s, a purpose which could thus use the to him most sacred of things, it was impossible to distrust. In respectful silence we took the places assigned to us close round the tomb, but hidden from the sight of any one approaching. I pitied the others, especially Michael. I had myself been apprenticed by my former visits to this watching horror, and yet I, who had up to an hour ago repudiated the proofs, felt my heart sink within me. Never did tombs look so ghastly white. Never did cypress, or yew, or juniper so seem the embodiment of funeral gloom. Never did tree or grass wave or rustle so ominously. Never did bough creak so mysteriously, and never did the far-away howling of dogs send such a woeful presage through the night.

There was a long spell of silence, big, aching, void, and then from the Professor a keen “S-s-s-s!” He pointed, and far down the avenue of yews we saw a white figure advance, a dim white figure, which held something dark at its breast. The figure stopped, and at the moment a ray of moonlight fell upon the masses of driving clouds, and showed in startling prominence a dark-haired woman, dressed in the cerements of the grave. We could not see the face, for it was bent down over what we saw to be a fair-haired child. There was a pause and a sharp little cry, such as a child gives in sleep, or a dog as it lies before the fire and dreams. We were starting forward, but the Professor’s warning hand, seen by us as he stood behind a yew tree, kept us back. And then as we looked the white figure moved forwards again. It was now near enough for us to see clearly, and the moonlight still held. My own heart grew cold as ice, and I could hear the gasp of Arthur, as we recognized the features of Lucy Westenra. Lucy Westenra, but yet how changed. The sweetness was turned to adamantine, heartless cruelty, and the purity to voluptuous wantonness.

Van Helsing stepped out, and obedient to his gesture, we all advanced too. The four of us ranged in a line before the door of the tomb. Van Helsing raised his lantern and drew the slide. By the concentrated light that fell on Lucy’s face we could see that the lips were crimson with fresh blood, and that the stream had trickled over her chin and stained the purity of her lawn death robe.

We shuddered with horror. I could see by the tremulous light that even Von Habsburg’s iron nerve had failed. Michael was next to me, and if I had not seized his arm and held him up, he would have fallen.

When Loukia, I call the thing that was before us Loukia because it bore her shape, saw us she drew back with an angry snarl, such as a cat gives when taken unawares, then her eyes ranged over us. Loukia’s eyes in form and color, but Lucy’s eyes unclean and full of hell fire, instead of the pure, gentle orbs we knew. At that moment the remnant of my love passed into hate and loathing. Had she then to be killed, I could have done it with savage delight. As she looked, her eyes blazed with unholy light, and the face became wreathed with a voluptuous smile. Oh, God, how it made me shudder to see it! With a careless motion, she flung to the ground, callous as a devil, the child that up to now she had clutched strenuously to her breast, growling over it as a dog growls over a bone. The child gave a sharp cry, and lay there moaning. There was a cold-bloodedness in the act which wrung a groan from Michael. When she advanced to him with outstretched arms and a wanton smile he fell back and hid his face in his hands.

She still advanced, however, and with a languorous, voluptuous grace, said, “Come to me, Michael. Leave these others and come to me. My arms are hungry for you. Come, and we can rest together. Come, my husband, come!”

There was something diabolically sweet in her tones, something of the tinkling of glass when struck, which rang through the brains even of us who heard the words addressed to another.

As for Michael, he seemed under a spell, moving his hands from his face, he opened wide his arms. She was leaping for them, when Von Habsburg sprang forward and held between them his little golden crucifix. She recoiled from it, and, with a suddenly distorted face, full of rage, dashed past him as if to enter the tomb.

When within a foot or two of the door, however, she stopped, as if arrested by some irresistible force. Then she turned, and her face was shown in the clear burst of moonlight and by the lamp, which had now no quiver from Von Habsburg’s nerves. Never did I see such baffled malice on a face, and never, I trust, shall such ever be seen again by mortal eyes. The beautiful color became livid, the eyes seemed to throw out sparks of hell fire, the brows were wrinkled as though the folds of flesh were the coils of Medusa’s snakes, and the lovely, blood-stained mouth grew to an open square, as in the passion masks of the Hellenes and Japanese. If ever a face meant death, if looks could kill, we saw it at that moment.

And so for full half a minute, which seemed an eternity, she remained between the lifted crucifix and the sacred closing of her means of entry.

Von Habsburg broke the silence by asking Michael, “Answer me, oh my friend! Am I to proceed in my work?”

“Do as you will, friend. Do as you will. There can be no horror like this ever any more.” And he groaned in spirit.

Quintus and I simultaneously moved towards him, and took his arms. We could hear the click of the closing lantern as Von Habsburg held it down. Coming close to the tomb, he began to remove from the chinks some of the sacred emblem which he had placed there. We all looked on with horrified amazement as we saw, when he stood back, the woman, with a corporeal body as real at that moment as our own, pass through the interstice where scarce a knife blade could have gone. We all felt a glad sense of relief when we saw the Professor calmly restoring the strings of putty to the edges of the door.

When this was done, he lifted the child and said, “Come now, my friends. We can do no more till tomorrow. There is a funeral at noon, so here we shall all come before long after that. The friends of the dead will all be gone by two, and when the sexton locks the gate we shall remain. Then there is more to do, but not like this of tonight. As for this little one, he is not much harmed, and by tomorrow night he shall be well. We shall leave him where the police will find him, as on the other night, and then to home.”

Coming close to Michael, he said, “My friend Michael, you have had a sore trial, but after, when you look back, you will see how it was necessary. You are now in the bitter waters, my child. By this time tomorrow you will, please God, have passed them, and have drunk of the sweet waters. So do not mourn over-much. Till then I shall not ask you to forgive me.”

Michael and Quintus came home with me, and we tried to cheer each other on the way. We had left behind the child in safety, and were tired. So we all slept with more or less reality of sleep.29 September, night.

A little before twelve o’clock we three, Michael, Markos Quintus, and myself, called for the Professor. It was odd to notice that by common consent we had all put on black clothes. Of course, Michael wore black, for he was in deep mourning, but the rest of us wore it by instinct. We got to the graveyard by half-past one, and strolled about, keeping out of official observation, so that when the gravediggers had completed their task and the sexton under the belief that every one had gone, had locked the gate, we had the place all to ourselves. Von Habsburg, instead of his little black bag, had with him a long leather one, something like a tzykanion bag. It was manifestly of fair weight.

When we were alone and had heard the last of the footsteps die out up the road, we silently, and as if by ordered intention, followed the Professor to the tomb. He unlocked the door, and we entered, closing it behind us. Then he took from his bag the lantern, which he lit, and also two wax candles, which, when lighted, he stuck by melting their own ends, on other coffins, so that they might give light sufficient to work by. When he again lifted the lid off Loukia’s coffin we all looked, Michael trembling like an aspen, and saw that the corpse lay there in all its death beauty. But there was no love in my own heart, nothing but loathing for the foul Thing which had taken Loukia’s shape without her soul. I could see even Michael’s face grow hard as he looked. Presently he said to Von Habsburg, “Is this really Loukia’s body, or only a demon in her shape?”

“It is her body, and yet not it. But wait a while, and you shall see her as she was, and is.”

When all was ready, Von Habsburg said, “Before we do anything, let me tell you this. It is out of the lore and experience of the ancients and of all those who have studied the powers of the Un-Dead. When they become such, there comes with the change the curse of immortality. They cannot die, but must go on age after age adding new victims and multiplying the evils of the world. For all that die from the preying of the Un-dead become themselves Un-dead, and prey on their kind. And so the circle goes on ever widening, like as the ripples from a stone thrown in the water. Friend Michael, if you had met that kiss which you know of before poor Loukia die, or again, last night when you open your arms to her, you would in time, when you had died, have become nosferatu, as they call it in Carpathia and the Slavic lands, and would for all time make more of those Un-Deads that so have filled us with horror. The career of this so unhappy dear lady is but just begun. Those children whose blood she sucked are not as yet so much the worse, but if she lives on, Un-Dead, more and more they lose their blood and by her power over them they come to her, and so she draw their blood with that so wicked mouth. But if she die in truth, then all cease. The tiny wounds of the throats disappear, and they go back to their play unknowing ever of what has been. But of the most blessed of all, when this now Un-Dead be made to rest as true dead, then the soul of the poor lady whom we love shall again be free. Instead of working wickedness by night and growing more debased in the assimilating of it by day, she shall take her place with the other Angels. So that, my friend, it will be a blessed hand for her that shall strike the blow that sets her free. To this I am willing, but is there none amongst us who has a better right? Will it be no joy to think of hereafter in the silence of the night when sleep is not, ‘It was my hand that sent her to the stars. It was the hand of him that loved her best, the hand that of all she would herself have chosen, had it been to her to choose?’ Tell me if there be such a one amongst us?”

We all looked at Michael. He saw too, what we all did, the infinite kindness which suggested that his should be the hand which would restore Loukia to us as a holy, and not an unholy, memory. He stepped forward and said bravely, though his hand trembled, and his face was as pale as snow, “My true friend, from the bottom of my broken heart I thank you. Tell me what I am to do, and I shall not falter!”

Von Habsburg laid a hand on his shoulder, and said, “Brave lad! A moment’s courage, and it is done. This stake must be driven through her. It well be a fearful ordeal, be not deceived in that, but it will be only a short time, and you will then rejoice more than your pain was great. From this grim tomb you will emerge as though you tread on air. But you must not falter when once you have begun. Only think that we, your true friends, are round you, and that we pray for you all the time.”

“Go on,” said Michael hoarsely. “Tell me what I am to do.”

“Take this stake in your left hand, ready to place to the point over the heart, and the hammer in your right. Then when we begin our prayer for the dead, I shall read him, I have here the book, and the others shall follow, strike in God’s name, that so all may be well with the dead that we love and that the Un-Dead pass away.” Michael took the stake and the hammer, and when once his mind was set on action his hands never trembled nor even quivered. Von Habsburg opened his missal and began to read, and Quintus and I followed as well as we could.

Michael placed the point over the heart, and as I looked I could see its dint in the white flesh. Then he struck with all his might.

The thing in the coffin writhed, and a hideous, bloodcurdling screech came from the opened red lips. The body shook and quivered and twisted in wild contortions. The sharp white champed together till the lips were cut, and the mouth was smeared with a crimson foam. But Michael never faltered. He looked like a figure of Thor as his untrembling arm rose and fell, driving deeper and deeper the mercybearing stake, whilst the blood from the pierced heart welled and spurted up around it. His face was set, and high duty seemed to shine through it. The sight of it gave us courage so that our voices seemed to ring through the little vault.

And then the writhing and quivering of the body became less, and the teeth seemed to champ, and the face to quiver. Finally it lay still. The terrible task was over.

The hammer fell from Michael’s hand. He reeled and would have fallen had we not caught him. The great drops of sweat sprang from his forehead, and his breath came in broken gasps. It had indeed been an awful strain on him, and had he not been forced to his task by more than human considerations he could never have gone through with it. For a few minutes we were so taken up with him that we did not look towards the coffin. When we did, however, a murmur of startled surprise ran from one to the other of us. We gazed so eagerly that Michael rose, for he had been seated on the ground, and came and looked too, and then a glad strange light broke over his face and dispelled altogether the gloom of horror that lay upon it.

There, in the coffin lay no longer the foul Thing that we had so dreaded and grown to hate that the work of her destruction was yielded as a privilege to the one best entitled to it, but Loukia as we had seen her in life, with her face of unequalled sweetness and purity. True that there were there, as we had seen them in life, the traces of care and pain and waste. But these were all dear to us, for they marked her truth to what we knew. One and all we felt that the holy calm that lay like sunshine over the wasted face and form was only an earthly token and symbol of the calm that was to reign for ever.

Von Habsburg came and laid his hand on Michael’s shoulder, and said to him, “And now, Arthur my friend, dear lad, am I not forgiven?”

The reaction of the terrible strain came as he took the old man’s hand in his, and raising it to his lips, pressed it, and said, “Forgiven! God bless you that you have given my dear one her soul again, and me peace.” He put his hands on the Professor’s shoulder, and laying his head on his breast, cried for a while silently, whilst we stood unmoving.

When he raised his head Von Habsburg said to him, “And now, my child, you may kiss her. Kiss her dead lips if you will, as she would have you to, if for her to choose. For she is not a grinning devil now, not any more a foul Thing for all eternity. No longer she is the devil’s Un-Dead. She is God’s true dead, whose soul is with Him!”

Michael bent and kissed her, and then we sent him and Quintus out of the tomb. The Professor and I sawed the top off the stake, leaving the point of it in the body. Then we cut off the head and filled the mouth with garlic. We soldered up the leaden coffin, screwed on the coffin lid, and gathering up our belongings, came away. When the Professor locked the door he gave the key to Michael.

Outside the air was sweet, the sun shone, and the birds sang, and it seemed as if all nature were tuned to a different pitch. There was gladness and mirth and peace everywhere, for we were at rest ourselves on one account, and we were glad, though it was with a tempered joy.

Before we moved away Von Habsburg said, “Now, my friends, one step of our work is done, one the most harrowing to ourselves. But there remains a greater task, to find out the author of all this our sorrow and to stamp him out. I have clues which we can follow, but it is a long task, and a difficult one, and there is danger in it, and pain. Shall you not all help me? We have learned to believe, all of us, is it not so? And since so, do we not see our duty? Yes! And do we not promise to go on to the bitter end?”

Each in turn, we took his hand, and the promise was made. Then said the Professor as we moved off, “Two nights hence you shall meet with me and dine together at seven of the clock with friend John. I shall entreat two others, two that you know not as yet, and I shall be ready to all our work show and our plans unfold. Friend John, you come with me home, for I have much to consult you about, and you can help me. Tonight I leave for Vienna, but shall return tomorrow night. And then begins our great quest. But first I shall have much to say, so that you may know what to do and to dread. Then our promise shall be made to each other anew. For there is a terrible task before us, and once our feet are on the ploughshare we must not draw back.”Dr. Stavridis’s Diary

When we arrived at the Macedonia Hotel, Von Habsburg found a telegram waiting for him.

“Am coming up by train. Ioannes at [REDACTED]. Important news. Mara Dalassenos.”

The Professor was delighted. “Ah, that wonderful Madam Mara,” he said, “pearl among women! She arrive, but I cannot stay. She must go to your house, friend John. You must meet her at the station. Telegraph her en route so that she may be prepared.”

When the wire was dispatched he had a cup of tea. Over it he told me of a diary kept by Ioannes Dalassenos when abroad, and gave me a typewritten copy of it, as also of Mrs. Dalassenos diary at [REDACTED]. “Take these,” he said, “and study them well. When I have returned you will be master of all the facts, and we can then better enter on our inquisition. Keep them safe, for there is in them much of treasure. You will need all your faith, even you who have had such an experience as that of today. What is here told,” he laid his hand heavily and gravely on the packet of papers as he spoke, “may be the beginning of the end to you and me and many another, or it may sound the knell of the Un-Dead who walk the earth. Read all, I pray you, with the open mind, and if you can add in any way to the story here told do so, for it is all important. You have kept a diary of all these so strange things, is it not so? Yes! Then we shall go through all these together when we meet.” He then made ready for his departure and shortly drove off to Thessaloniki Street. I took my way to Hippodrome District, where I arrived about fifteen minutes before the train came in.

The crowd melted away, after the bustling fashion common to arrival platforms, and I was beginning to feel uneasy, lest I might miss my guest, when a sweet-faced, dainty looking girl stepped up to me, and after a quick glance said, “Dr. Stavridis, is it not?”

“And you are Mrs. Dalassenos!” I answered at once, whereupon she held out her hand.

“I knew you from the description of poor dear Loukia, but. . .” She stopped suddenly, and a quick blush overspread her face.

The blush that rose to my own cheeks somehow set us both at ease, for it was a tacit answer to her own. I got her luggage, which included a typewriter, and we took the Underground to Sophia Street, after I had sent a wire to my housekeeper to have a sitting room and a bedroom prepared at once for Mrs. Dalassenos.

In due time we arrived. She knew, of course, that the place was a lunatic asylum, but I could see that she was unable to repress a shudder when we entered.

She told me that, if she might, she would come presently to my study, as she had much to say. So here I am finishing my entry in my phonograph diary whilst I await her. As yet I have not had the chance of looking at the papers which Von Habsburg left with me, though they lie open before me. I must get her interested in something, so that I may have an opportunity of reading them. She does not know how precious time is, or what a task we have in hand. I must be careful not to frighten her. Here she is!Mara Dalassenos’s Journal

29 September.After I had tidied myself, I went down to Dr. Stavridis’s study. At the door I paused a moment, for I thought I heard him talking with some one. As, however, he had pressed me to be quick, I knocked at the door, and on his calling out, “Come in,” I entered.

To my intense surprise, there was no one with him. He was quite alone, and on the table opposite him was what I knew at once from the description to be a phonograph. I had never seen one, and was much interested.

“I hope I did not keep you waiting,” I said, “but I stayed at the door as I heard you talking, and thought there was someone with you.”

“Oh,” he replied with a smile, “I was only entering my diary.”

“Your diary?” I asked him in surprise.

“Yes,” he answered. “I keep it in this.” As he spoke he laid his hand on the phonograph. I felt quite excited over it, and blurted out, “Why, this beats even shorthand! May I hear it say something?”

“Certainly,” he replied with alacrity, and stood up to put it in train for speaking. Then he paused, and a troubled look overspread his face.

“The fact is,” he began awkwardly. “I only keep my diary in it, and as it is entirely, almost entirely, about my cases it may be awkward, that is, I mean . . .” He stopped, and I tried to help him out of his embarrassment.

“You helped to attend dear Loukia at the end. Let me hear how she died, for all that I know of her, I shall be very grateful. She was very, very dear to me.”

To my surprise, he answered, with a horrorstruck look in his face, “Tell you of her death? Not for the wide world!”

“Why not?” I asked, for some grave, terrible feeling was coming over me.

Again he paused, and I could see that he was trying to invent an excuse. At length, he stammered out, “You see, I do not know how to pick out any particular part of the diary.”

Even while he was speaking an idea dawned upon him, and he said with unconscious simplicity, in a different voice, and with the naivete of a child, “that’s quite true, upon my honor. Honest Cherokee!”

I could not but smile, at which he grimaced. “I gave myself away that time!” he said. “But do you know that, although I have kept the diary for months past, it never once struck me how I was going to find any particular part of it in case I wanted to look it up?”

By this time my mind was made up that the diary of a doctor who attended Loukia might have something to add to the sum of our knowledge of that terrible Being, and I said boldly, “Then, Dr. Stavridis, you had better let me copy it out for you on my typewriter.”

He grew to a positively deathly pallor as he said, “No! No! No! For all the world. I wouldn’t let you know that terrible story.!”

Then it was terrible. My intuition was right! For a moment, I thought, and as my eyes ranged the room, unconsciously looking for something or some opportunity to aid me, they lit on a great batch of typewriting on the table. His eyes caught the look in mine, and without his thinking, followed their direction. As they saw the parcel he realized my meaning.

“You do not know me,” I said. “When you have read those papers, my own diary and my husband’s also, which I have typed, you will know me better. I have not faltered in giving every thought of my own heart in this cause. But, of course, you do not know me, yet, and I must not expect you to trust me so far.”

He is certainly a man of noble nature. Poor dear Loukia was right about him. He stood up and opened a large drawer, in which were arranged in order a number of hollow cylinders of metal covered with dark wax, and said,

“You are quite right. I did not trust you because I did not know you. But I know you now, and let me say that I should have known you long ago. I know that Loukia told you of me. She told me of you too. May I make the only atonement in my power? Take the cylinders and hear them. The first half-dozen of them are personal to me, and they will not horrify you. Then you will know me better. Dinner will by then be ready. In the meantime I shall read over some of these documents, and shall be better able to understand certain things.”

He carried the phonograph himself up to my sitting room and adjusted it for me. Now I shall learn something pleasant, I am sure. For it will tell me the other side of a true love episode of which I know one side already.Dr. Stavridis’s Diary

29 September.I was so absorbed in that wonderful diary of Ioannes Dalassenos and that other of his wife that I let the time run on without thinking. Mrs. Dalassenos was not down when the maid came to announce dinner, so I said, “She is possibly tired. Let dinner wait an hour,” and I went on with my work. I had just finished Mrs. Dalassenos’s diary, when she came in. She looked sweetly pretty, but very sad, and her eyes were flushed with crying. This somehow moved me much. Of late I have had cause for tears, God knows! But the relief of them was denied me, and now the sight of those sweet eyes, brightened by recent tears, went straight to my heart. So I said as gently as I could, “I greatly fear I have distressed you.”

“Oh, no, not distressed me,” she replied. “But I have been more touched than I can say by your grief. That is a wonderful machine, but it is cruelly true. It told me, in its very tones, the anguish of your heart. It was like a soul crying out to Almighty God. No one must hear them spoken ever again! See, I have tried to be useful. I have copied out the words on my typewriter, and none other need now hear your heart beat, as I did.”

“No one need ever know, shall ever know,” I said in a low voice. She laid her hand on mine and said very gravely, “Ah, but they must!”

“Must! but why?” I asked.

“Because it is a part of the terrible story, a part of poor Loukia’s death and all that led to it. Because in the struggle which we have before us to rid the earth of this terrible monster we must have all the knowledge and all the help which we can get. I think that the cylinders which you gave me contained more than you intended me to know. But I can see that there are in your record many lights to this dark mystery. You will let me help, will you not? I know all up to a certain point, and I see already, though your diary only took me to 7 September, how poor Loukia was beset, and how her terrible doom was being wrought out. Ioannes and I have been working day and night since Professor Von Habsburg saw us. He is gone to [REDACTED] to get more information, and he will be here tomorrow to help us. We need have no secrets amongst us. Working together and with absolute trust, we can surely be stronger than if some of us were in the dark.”

She looked at me so appealingly, and at the same time manifested such courage and resolution in her bearing, that I gave in at once to her wishes. “You shall,” I said, “do as you like in the matter. God forgive me if I do wrong! There are terrible things yet to learn of. But if you have so far traveled on the road to poor Loukia’s death, you will not be content, I know, to remain in the dark. Nay, the end, the very end, may give you a gleam of peace. Come, there is dinner. We must keep one another strong for what is before us. We have a cruel and dreadful task. When you have eaten you shall learn the rest, and I shall answer any questions you ask, if there be anything which you do not understand, though it was apparent to us who were present.”Mara Dalassenos’s Journal

29 September.After dinner I came with Dr. Stavridis to his study. He brought back the phonograph from my room, and I took a chair, and arranged the phonograph so that I could touch it without getting up, and showed me how to stop it in case I should want to pause. Then he very thoughtfully took a chair, with his back to me, so that I might be as free as possible, and began to read. I put the forked metal to my ears and listened.

When the terrible story of Loukia’s death, and all that followed, was done, I lay back in my chair powerless. Fortunately I am not of a fainting disposition. When Dr. Stavridis saw me he jumped up with a horrified exclamation, and hurriedly taking a case bottle from the cupboard, gave me some brandy, which in a few minutes somewhat restored me. My brain was all in a whirl, and only that there came through all the multitude of horrors, the holy ray of light that my dear Loukia was at last at peace, I do not think I could have borne it without making a scene. It is all so wild and mysterious, and strange that if I had not known Ioannes experience in Transylvania I could not have believed. As it was, I didn’t know what to believe, and so got out of my difficulty by attending to something else. I took the cover off my typewriter, and said to Dr. Stavridis,

“Let me write this all out now. We must be ready for Dr. Von Habsburg when he comes. I have sent a telegram to Ioannes to come on here when he arrives in Constantinople from Athens. In this matter dates are everything, and I think that if we get all of our material ready, and have every item put in chronological order, we shall have done much.

“You tell me that Senator Doukas and Mr. Quintus are coming too. Let us be able to tell them when they come.”

He accordingly set the phonograph at a slow pace, and I began to typewrite from the beginning of the seventeenth cylinder. I used manifold, and so took three copies of the diary, just as I had done with the rest. It was late when I got through, but Dr. Stavridis went about his work of going his round of the patients. When he had finished he came back and sat near me, reading, so that I did not feel too lonely whilst I worked. How good and thoughtful he is. The world seems full of good men, even if there are monsters in it.

Before I left him I remembered what Ioannes put in his diary of the Professor’s perturbation at reading something in an evening paper at the station at Nicaea, so, seeing that Dr. Stavrids keeps his newspapers, I borrowed the files of ‘The Blachernae Gazette’ and ‘The Adrianopolis Gazette’ and took them to my room. I remember how much the ‘Daily News’ and ‘The Athens Gazette’, of which I had made cuttings, had helped us to understand the terrible events at [REDACTED] when Count Dracula landed, so I shall look through the evening papers since then, and perhaps I shall get some new light. I am not sleepy, and the work will help to keep me quiet.Dr. Stavridis’s Diary

30 September.Mr. Dalassenos arrived at nine o’clock. He got his wife’s wire just before starting. He is uncommonly clever, if one can judge from his face, and full of energy. If this journal be true, and judging by one’s own wonderful experiences, it must be, he is also a man of great nerve. That going down to the vault a second time was a remarkable piece of daring. After reading his account of it I was prepared to meet a good specimen of manhood, but hardly the quiet, business-like gentleman who came here today.

LATER.–After lunch Dalassenos and his wife went back to their own room, and as I passed a while ago I heard the click of the typewriter. They are hard at it. Mrs. Dalassenos says that they are knitting together in chronological order every scrap of evidence they have. Dalassenos has got the letters between the consignee of the boxes at strategic points in Constantinople and the carriers in the capital who took charge of them. He is now reading his wife’s transcript of my diary. I wonder what they make out of it. Here it is . . .