The Empire Strikes Back 97- 1890-1895

Announcing the Session

Senators,

Your presence is requested for a State of the Empire address on January 1st 1895, at Blachernae Palace.

These newspapers are considered significant by the archivists.

And the Senate’s world map has been updated.

Senators' Discussion

Great wars…

how interesting! It is time for our empire to show its true might and crush all opposition that may come before it! I say we consolidate our holdings in Asia and Africa and then launch a major offensive against Russia! We should also conquer the rest of the British isles to make sure we are not threatened in Britannia. We must seek a middle path in politics without the violence of the reactionaries and communists!

*Goes off muttering about low glass prices and lower taxes

- Senator Ambrosio Palaiologos, Duke of Nicaea, Governor of Britannia

Michael arrives in the room, accompanied by his bodyguards.

Ah, hello fellow senators, it is good to see you all again! I’ve recently been to the Pandidakterion’s Psychology Department, and they’ve told me (you can read the note here–Michael passes around a letter signed by the Chair of the Psychology Department) that such outbreaks as what occurred at our last session are rare occurrences and should decrease in frequency and intensity with time. They have declared me sane enough to carry out my duties to the state effectively. Now on to the pressing matters.

There has been a small rebellion in Wales. You may or may not have heard about it, most likely because the Ministry of Security detected it early and dispatched a couple legions to the area to defeat them before they could do any serious damage.

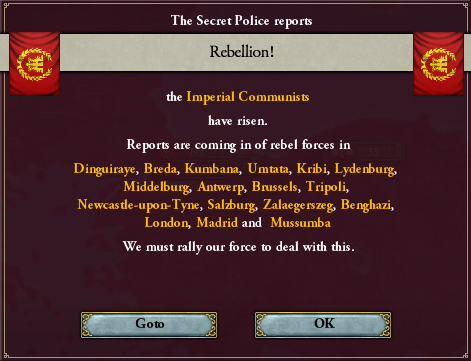

You all know the 1891 communist rebellion that was crushed. I witnessed it personally. They besieged my estates in Jerusalem and Damascus, the latter of which was burned down. I was in Jerusalem at the time, and I saw how the people were angry to the point of rebellion. They must be granted social reforms to alleviate their suffering. But political reforms, I fear, would likely make the situation worse. And then the communists rose up in 1894…we need a change we can believe in, and fast!

Tractors would boost the production efficiency of the Empire manyfold. I see many opportunities to be made from this invention.

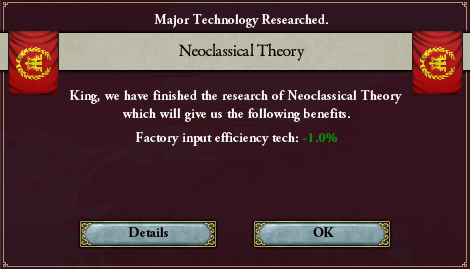

The Germanics have invented flying machines? Impressive, for barbarians. We already have airships such as the La France, which I’m sure you all remember was rechristened the Veronica after Konstantinos’s Rebellion. And speaking of Konstantinos’s Rebellion…

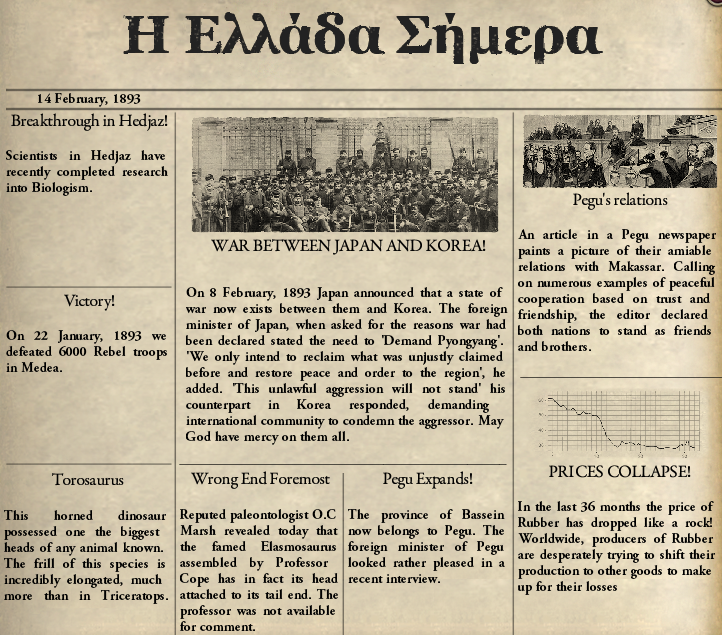

It appears that we didn’t defeat all of the traitor Konstantinos’s forces. Some of them escaped to Burgundy, Anatolia, and North Africa, where they were found by the Ministry of Security and defeated within the month. However, others rose up in Greece, near my home in Athens. They were led by this man.

Michael passes around a photo of a bearded man wearing imperial regalia.

This is Markos Angelos, self-proclaimed Basileus Basileon and Isapostolos. He is guilty of the following crimes: treason, plotting against the imperial family, murder, manslaughter, illegal possession of military equipment, blasphemy, heresy, desecrating the Empire’s honor, wearing imperial purple, etc., etc. He managed to escape the legions that crushed his rebels in Greece and is now on the run, presumably to Russia or Germany. The Ministry of Security has put out a notice stating that this man is heavily armed and dangerous. Any citizen who finds this man is legally obliged to capture or kill him at all costs before he managed to escape over the border into another country. The reward is to be determined by Her Imperial Highness.

To the members of the Angeloi family in attendance, on behalf of the Ministry of Security I will not arrest any member of your family based solely on your relationship with Markos Angelos. In return I expect that all of you cooperate fully with this manhunt and investigation.

Anybody else go to the World’s Fair, the one that occurred a couple months before the 1891 rebellion? Marvelous stuff they had there, including one of those new “telephone” devices. Imagine having a telegraph but hearing somebody else’s voice over the line! This is the pinnacle of technology! In a hundred years who knows what we’ll have?

Marsh…that eccentric professor can’t get a skeleton right! Funniest thing I’ve read in a while!

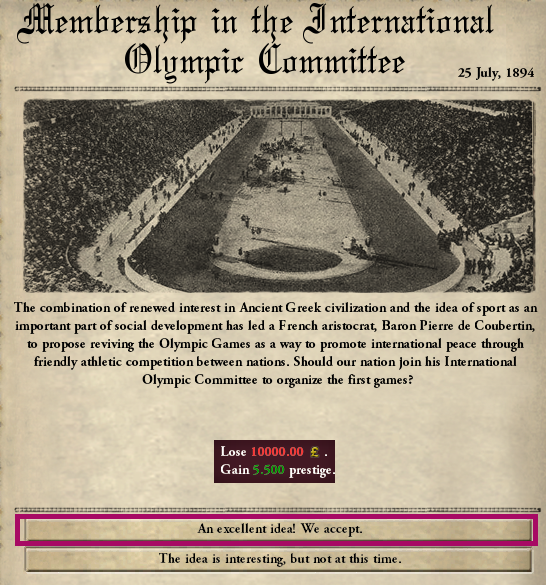

I see we have brought back the Olympics. As we are the Romans, it is only fitting that we bring back a Roman tradition to show off the glory of our youth against those of other nations.

But if the Olympics can bring the world together, the Great Wars which we have developed have the potential to destroy it. We must be careful when waging war from now on, as one small spark could set the entire world on fire.

Speaking of war, I’ve noticed that the Ming have fallen to reactionaries yet again and that Japan has invaded Korea. One of these days, a global war is probably going to be sparked by some silly thing in China…or in Central Europe.

It’s good that we expanded in the Philippines to expand our influence in Asia and reduce that of Russia. They must be brought down to size!

And the UTA…have they gone mad? Annexing everything in sight, conquering Alaska and Hawaii, building these “pre-dreadnought” ships? These ships are obviously built to challenge our control of the seas and to increase their power in Asia. We cannot let them stand as they are, for they will eventually come after us in an attempt to assert global hegemony! And if they have built “pre-dreadnoughts,” imagine what the actual dreadnoughts look like.

That is all for now.

Michael takes his seat.

My esteemed Senators and those sitting in the Cheap Seats on the Conservative side.

I must put forward a protest on the brutal treatment of the workers of this great Empire. After notifiying the police and local government about our lawful protests against the conditions of the workers and the poor, the Minister for Security, the one with the note to say that he is sane, released the army on these peaceful protests stirring up a hornets nest of discontent and rage. Had a gentler and more sane minister been in charge perhaps this could have been averted.

If the Minister can not perform his duties perhaps it is time to remove him from his post?

Also with our current allies & vassals should we not use the invention of these so called Great Wars, can we not look to dismantle the perfidious Russians once and for all?

- Senator & Chief of Staff Στήβεν Γκρέυ

When did I ever order the army to attack peaceful protestors? When were they peaceful? Even if they were peaceful, I do not have the authority to order armies around, just to advise the General Staff on matters of national security. You ought to direct your grievances to them instead of me!

And I’ll have you know, I am in complete favor of better working conditions, along with my father and my grandfather before me! I have always been in support of it and I certainly am in support of it now! Your claims are unfounded, and if this were not the Senate I would accuse you of conspiring to remove my from my post!

- Senator Doukas

Well then my fellow Senator, I refer you to the notes of your speech on the Hansard, you mention that you have personally dispatched legions to a revolt in Wales.

So my dear sir you either seek to hide the truth of your use of the Legions as your own private police force or once again have overstepped your jurisdiction.

My dear sir, I simply seeking to have a Minister that is capable of handling these matters without half the Empire burning down.

I would ask Senators Theodosio and Favero but I fear they are too busy repressing the masses.

- Senator Gray

Sir,

Those rebels were hardly anything but peaceful. I was given orders directly from the Throne to order those armies and nothing more. I have the imperial edict here if you want to see it. But I do not have command of all legions, just those few. And only the Empress may replace me, not you. Understand?- Senator Doukas

“Senator Doukas,” says Alexios politely but cooly, “I only have recently taken my seat in the Boule, but I don’t think that you have the power to do that to an active senator without the Basilissa’s permission. Further, I’m not sure how you Foideratoi handle matters, but we in Patrikioi tend to ask questions and then await answers, rather than trying to extract confessions in return for not imprisoning or torturing innocent people.”

Sir,

When did I ever say I was going to torture and imprison people? I merely stated that I will protect them from any prosecution by the Ministry of Security while I ask them questions regarding Markos Angelos. And I was directing this to the senator’s family members; the senator himself cannot be investigated without the permission of the Empress, of course. If anything else still offfends the rule of law, though, I would gladly change my strategies.

- Doukas

i must request that we end this pointless bikering and actually attend to matters of state

- Alexander smithereens

My Empress, I would like to note my acceptance into the I Koinotita and within that role given the violence brought forth in your name by those that continue to abuse their power and for the ultimate crime of picking on grammatical errors, I demand that a vote of no confidence in the Senate. If this body is not capable of action, I suggest new leadership be chosen.

The I Koinotita are the fastest growing political party and only with our guidance can the workers be sure that their rights will be protected and that the dead wood of the past be removed.

- Aiden Gray, Senator & Chief of Staff

I sometimes wonder if you all even remember that the Senate is purely an advisory body. There is no “voting”, for we were never elected. There is no “action”, for we only carry out our duties when the Empress demands it. If the Empress so wished it, she could disband this whole body and rule directly. Instead she is wise enough to seek our counsel and use the wisdom of others to aid in her rule of our fair empire. Those who feel their colleagues do not belong here should realize that we are all here at the Empress’s behest. We do not have the power to dismiss each other. If you have a problem with that, take it up with the Empress. If she is wise enough, she’ll dismiss you bickering lot and continue on with her reign free of your banter.

In fact, if this petty political squabbling continues, I’d advise the Empress, as is my duty as a member of the Senate, to disband the Senate entirely and rule without our guidance. If my colleagues feel that we are all equally incompetent, I will not argue with their general acceptance of one another’s idiocy and accept that the Empress would be better off ruling without our guidance. Either that or my fellow senators should accept one another’s faults and accept that their role is to advise Her Imperial Majesty instead of attempting to undermine one another’s pathetic political careers.

- Senator Leonardo Favero

I agree entirely Senator Favero, one has to wonder though, how the Empress’ Minister of Intelligence was not able to foresee the brutal repression of hundreds of thousands of workers throughout the empire or perhaps given your support of the Patrikioi perhaps this information was at hand and instead of performing your duties “The Butcher of Africa” allowed these matters to descend into the farce that they became.

And my entire point Senator is why would a party with very little support outside of the 1% of wealthy old aristocracy hold such an important role within the state, we may be an advisory body, but if those in Imperial sanctioned office do not perform their duty simply to weaken other parties and the Empire as a whole, in fact border on acts of treason, the Empress must be made aware of the danger in trusting the advice from such an unrepresentative body.

- Senator Gray

((Public))

Can we all just get back to the matter of the traitor, Markos Angelos, instead of bickering about socialism and personal attacks and the existence of the Senate?! Angelos is a threat to the Empire as long as he is at large and I intend to bring him to justice! Trying to remove other senators or dismantle the Senate itself for personal and/or ideological motives will only benefit him!

((Private))

Meanwhile…Letter, Dr. Stavridis to Hon. Michael Doukas

6 SeptemberMy dear Mike,

My news today is not so good. Loukia this morning had gone back a bit. There is, however, one good thing which has arisen from it. Mrs. Este-Ravenna was naturally anxious concerning Loukia, and has consulted me professionally about her. I took advantage of the opportunity, and told her that my old master, Von Habsburg, the great specialist, was coming to stay with me, and that I would put her in his charge conjointly with myself. So now we can come and go without alarming her unduly, for a shock to her would mean sudden death, and this, in Loukia’s weak condition, might be disastrous to her. We are hedged in with difficulties, all of us, my poor fellow, but, please God, we shall come through them all right. If any need I shall write, so that, if you do not hear from me, take it for granted that I am simply waiting for news, In haste,

Yours ever,

Stavridis

Dr. Stavridis’s Diary

7 September.The first thing Von Habsburg said to me when we met at Thessaloniki Street was, “Have du said anyzing zo our young friend, zo lover of her?”

“No,” I said. “I waited till I had seen you, as I said in my telegram. I wrote him a letter simply telling him that you were coming, as Miss Este-Ravenna was not so well, and that I should let him know if need be.”

“Gut, mein friend,” he said. “Quite right! Better he not know as yet. Perhaps he vill never know. Ich pray so, but if it be needed, then he shall know all. And, mein gut friend John, let me caution you. Du deal vith zhe madmen. All men are mad in some vay or zhe other, and inasmuch as du deal discreetly with your madmen, so deal vith Gott’s madmen too, zhe rest of zhe vorld. Du tell not your madmen vhat du do nor vhy du do it. Du tell them not vhat du zhink. So du shall keep knowledge in its place, vhere it may rest, vhere it may gather its kind around it und breed. Du and Ich shall keep as yet vhat ve know here, und here.” He touched me on the heart and on the forehead, and then touched himself the same way. “Ich hab for mein self zhoughts at zhe present. Later Ich shall unfold to du.”

“Why not now?” I asked. “It may do some good. We may arrive at some decision.”

He looked at me and said,”Mein friend John, vhen zhe corn ist grown, even before it has ripened, vhile zhe milk of its mother earth is in him, and zhe sunshine has not yet begun zo paint him vith his gold, zhe husbandman he pull zhe ear und rub him between his rough hands, und blow away zhe green chaff, und say to du, ‘Look! He’s good corn, he vill make a good crop when zhe time comes.’ “

I did not see the application and told him so. For reply he reached over and took my ear in his hand and pulled it playfully, as he used long ago to do at lectures, and said, “Zhe gut husbandman tell du so zhen because he knows, but not till zhen. But du do not find zhe gut husbandman dig up his planted corn to see if he grow. Zhat is for zhe kinder vho play at husbandry, und nicht for zhose vho take it as of zhe vork of zheir life. See du now, friend John? Ich have sown mein corn, and Nature has her vork to do in making it sprout, if he sprout at all, there’s some promise, and Ich wait till the ear begins to swell.” He broke off, for he evidently saw that I understood. Then he went on gravely, “Du vere always a careful student, and your case book vas ever more full than the rest. Und Ich trust zhat gut habit have nichtt fail. Remember, mein friend, zhat knowledge ist stronger than memory, und ve should nicht trust zhe veaker. Even if du have not kept zhe gut practice, let mich tell du zhat zhis case of our dear frau ist eine zhat may be, mind, Ich say may be, of such interest to us und others zhat all zhe rest may not make him kick zhe beam, as your people say. Take zhen good note of it. Nothing ist too small. Ich counsel you, put down in record even your doubts und surmises. Hereafter it may be of interest to du to see how true you guess. Ve learn from failure, not from success!”

When I described Lucy’s symptoms, the same as before, but infinitely more marked, he looked very grave, but said nothing. He took with him a bag in which were many instruments and drugs, “zhe ghastly paraphernalia of our beneficial trade,” as he once called, in one of his lectures, the equipment of a professor of the healing craft.

When we were shown in, Mrs. Este-Ravenna met us. She was alarmed, but not nearly so much as I expected to find her. Nature in one of her beneficient moods has ordained that even death has some antidote to its own terrors. Here, in a case where any shock may prove fatal, matters are so ordered that, from some cause or other, the things not personal, even the terrible change in her daughter to whom she is so attached, do not seem to reach her. It is something like the way dame Nature gathers round a foreign body an envelope of some insensitive tissue which can protect from evil that which it would otherwise harm by contact. If this be an ordered selfishness, then we should pause before we condemn any one for the vice of egoism, for there may be deeper root for its causes than we have knowledge of.

I used my knowledge of this phase of spiritual pathology, and set down a rule that she should not be present with Loukia, or think of her illness more than was absolutely required. She assented readily, so readily that I saw again the hand of Nature fighting for life. Von Habsburg and I were shown up to Loukia’s room. If I was shocked when I saw her yesterday, I was horrified when I saw her today.

She was ghastly, chalkily pale. The red seemed to have gone even from her lips and gums, and the bones of her face stood out prominently. Her breathing was painful to see or hear. Von Habsburg’s face grew set as marble, and his eyebrows converged till they almost touched over his nose. Loukia lay motionless, and did not seem to have strength to speak, so for a while we were all silent. Then Von Habsburg beckoned to me, and we went gently out of the room. The instant we had closed the door he stepped quickly along the passage to the next door, which was open. Then he pulled me quickly in with him and closed the door. “Mein gott!” he said. “Zhis is dreadful. Zhere is nicht time to be lost. She vill die fur sheer vant of blut to keep zhe heart’s action as it should be. Zhere must be a transfusion of blut at once. Ist it du or mich?”

“I am younger and stronger, Professor. It must be me.”

“Zhen get ready at once. Ich vill bring up mein bag. Ich am prepared.”

I went downstairs with him, and as we were going there was a knock at the hall door. When we reached the hall, the maid had just opened the door, and Michael was stepping quickly in. He rushed up to me, saying in an eager whisper,

“Jim, I was so anxious. I read between the lines of your letter, and have been in an agony. The mother was better, so I ran down here to see for myself. Is not that gentleman Dr. Von Habsburg? I am so thankful to you, sir, for coming.”

When first the Professor’s eye had lit upon him, he had been angry at his interruption at such a time, but now, as he took in his stalwart proportions and recognized the strong young manhood which seemed to emanate from him, his eyes gleamed. Without a pause he said to him as he held out his hand,

“Sir, du hab come in time. Du are zhe lover of our dear frau. She is bad, very, very bad. Nein, mein kinder, do nicht go like zhat.”

For he suddenly grew pale and sat down in a chair almost fainting. “Du are to help her. Du can do more zhan any zhat live, and your courage ist your best help.”

“What can I do?” asked Michael hoarsely. “Tell me, and I shall do it. My life is hers’ and I would give the last drop of blood in my body for her.”

The Professor has a strongly humorous side, and I could from old knowledge detect a trace of its origin in his answer.

“Mein young sir, Ich do not ask so much as zhat, not zhe last!”

“What shall I do?” There was fire in his eyes, and his open nostrils quivered with intent. Von Habsburg slapped him on the shoulder.

“Come!” he said. “Du are a man, and it ist a man ve vant. Du are better than mich, better than mein friend John.” Michael looked bewildered, and the Professor went on by explaining in a kindly way.

“Young frau is bad, very bad. She vants blut, and blut she must have or die. Mein friend John and Ich have consulted, and ve are about to perform vhat ve call transfusion of blut, to transfer from full veins of one to zhe empty veins which pine for him. John was to give his blut, as he ist zhe more young and strong zhan mich.”–Here Michael took my hand and wrung it hard in silence.–“But now du are here, du are more good zhan us, old or young, vho toil much in zhe vorld of zhought. Our nerves are nicht so calm and our blut so bright zhan yours!”

Michael turned to him and said, “If you only knew how gladly I would die for her you would understand . . .” He stopped with a sort of choke in his voice.

“Gut boy!” said Von Habsburg. “In zhe not-so-far-off du vill be happy zhat du have done all for her du love. Come now and be silent. Du shall kiss her vonce before it is done, but zhen du must go, and du must leave at mein sign. Say nicht a word to Fraulein. du know how it ist vith her. Zhere must be no shock, any knowledge of zhis would be one. Come!”

We all went up to Loukia’s room. Michael by direction remained outside. Michael turned her head and looked at us, but said nothing. She was not asleep, but she was simply too weak to make the effort. Her eyes spoke to us, that was all.

Von Habsburg took some things from his bag and laid them on a little table out of sight. Then he mixed a narcotic, and coming over to the bed, said cheerily, “Now, little frau, here ist your medicine. Drink it off, like a gut kinder. See, Ich lift du so zhat to svallow ist easy. Ja.” She had made the effort with success.

It astonished me how long the drug took to act. This, in fact, marked the extent of her weakness. The time seemed endless until sleep began to flicker in her eyelids. At last, however, the narcotic began to manifest its potency, and she fell into a deep sleep. When the Professor was satisfied, he called Michael into the room, and bade him strip off his coat. Then he added, “Du may take zhat one little kiss vhiles Ich bring over zhe table. Friend John, help to mich!” So neither of us looked whilst he bent over her.

Von Habsburg, turning to me, said, “He ist so young und strong, and of blut so pure zhat ve need nicht defibrinate it.”

Then with swiftness, but with absolute method, Von Habsburg performed the operation. As the transfusion went on, something like life seemed to come back to poor Loukia’s cheeks, and through Michael’s growing pallor the joy of his face seemed absolutely to shine. After a bit I began to grow anxious, for the loss of blood was telling on Michael, strong man as he was. It gave me an idea of what a terrible strain Loukia’s system must have undergone that what weakened Michael only partially restored her.

But the Professor’s face was set, and he stood watch in hand, and with his eyes fixed now on the patient and now on Michael. I could hear my own heart beat. Presently, he said in a soft voice, “Do nicht stir an instant. It ist enough. Du attend him. Ich vill look to her.”

When all was over, I could see how much Michael was weakened. I dressed the wound and took his arm to bring him away, when Von Habsburg spoke without turning round, the man seems to have eyes in the back of his head,”Zhe brave lover, Ich zhink, deserve another kiss, vhich he shall have presently.” And as he had now finished his operation, he adjusted the pillow to the patient’s head. As he did so the narrow black velvet band which she seems always to wear round her throat, buckled with an old diamond buckle which her lover had given her, was dragged a little up, and showed a red mark on her throat.

Michael did not notice it, but I could hear the deep hiss of indrawn breath which is one of Von Habsburg’s ways of betraying emotion. He said nothing at the moment, but turned to me, saying, “Now take down our brave young lover, give him of zhe port wine, and let him lie down a vhile. He must zhen go home und rest, sleep much and eat much, zhat he may be recruited of vhat he has so given to his love. He must nicht stay here. Hold a moment! Ich may take it, sir, that you are anxious of result. Then bring it vith du, that in all ways zhe operation is successful. Du have saved her life zhis time, and du can go home and rest easy in mind zhat all zhat can be is. Ich shall tell her all vhen she is vell. She shall love du none zhe less for vhat you have done. Goodbye.”

When Michael had gone I went back to the room. Loukia was sleeping gently, but her breathing was stronger. I could see the counterpane move as her breast heaved. By the bedside sat Von Habsburg, looking at her intently. The velvet band again covered the red mark. I asked the Professor in a whisper, “What do you make of that mark on her throat?”

“Vhat do du make of it?”

“I have not examined it yet,” I answered, and then and there proceeded to loose the band. Just over the external jugular vein there were two punctures, not large, but not wholesome looking. There was no sign of disease, but the edges were white and worn looking, as if by some trituration. It at once occurred to me that that this wound, or whatever it was, might be the means of that manifest loss of blood. But I abandoned the idea as soon as it formed, for such a thing could not be. The whole bed would have been drenched to a scarlet with the blood which the girl must have lost to leave such a pallor as she had before the transfusion.

“Vell?” said Van Helsing.

“Well,” said I. “I can make nothing of it.”

The Professor stood up. “Ich must go back to Vienna tonight,” he said “Zhere are books and things there which I want. Du must remain here all nacht, und du must not let your sight pass from her.”

“Shall I have a nurse?” I asked.

“Ve are zhe best nurses, du and Ich. Du keep vatch all nacht. See zhat she is vell fed, and zhat nothing disturbs her. Du must not sleep all zhe nacht. Later on ve can sleep, du and Ich. Ich shall be back as soon as possible. And zhen ve may begin.”

“May begin?” I said. “What on earth do you mean?”

“Ve shall see!” he answered, as he hurried out. He came back a moment later and put his head inside the door and said with a warning finger held up, “Remember, she ist your charge. If du leave her, and harm befall, du shall nicht sleep easy hereafter!”Dr. Stavridis’s Diary–Continued

8 September.I sat up all night with Loukia. The opiate worked itself off towards dusk, and she waked naturally. She looked a different being from what she had been before the operation. Her spirits even were good, and she was full of a happy vivacity, but I could see evidences of the absolute prostration which she had undergone. When I told Mrs. Este-Ravenna that Dr. Von Habsburg had directed that I should sit up with her, she almost pooh-poohed the idea, pointing out her daughter’s renewed strength and excellent spirits. I was firm, however, and made preparations for my long vigil. When her maid had prepared her for the night I came in, having in the meantime had supper, and took a seat by the bedside.

She did not in any way make objection, but looked at me gratefully whenever I caught her eye. After a long spell she seemed sinking off to sleep, but with an effort seemed to pull herself together and shook it off. It was apparent that she did not want to sleep, so I tackled the subject at once.

“You do not want to sleep?”

“No. I am afraid.”

“Afraid to go to sleep! Why so? It is the boon we all crave for.”

“Ah, not if you were like me, if sleep was to you a presage of horror!”

“A presage of horror! What on earth do you mean?”

“I don’t know. Oh, I don’t know. And that is what is so terrible. All this weakness comes to me in sleep, until I dread the very thought.”

“But, my dear girl, you may sleep tonight. I am here watching you, and I can promise that nothing will happen.”

“Ah, I can trust you!” she said.

I seized the opportunity, and said, “I promise that if I see any evidence of bad dreams I will wake you at once.”

“You will? Oh, will you really? How good you are to me. Then I will sleep!” And almost at the word she gave a deep sigh of relief, and sank back, asleep.

All night long I watched by her. She never stirred, but slept on and on in a deep, tranquil, life-giving, healthgiving sleep. Her lips were slightly parted, and her breast rose and fell with the regularity of a pendulum. There was a smile on her face, and it was evident that no bad dreams had come to disturb her peace of mind.

In the early morning her maid came, and I left her in her care and took myself back home, for I was anxious about many things. I sent a short wire to Von Habsburg and Michael, telling them of the excellent result of the operation. My own work, with its manifold arrears, took me all day to clear off. It was dark when I was able to inquire about my zoophagous patient. The report was good. He had been quite quiet for the past day and night. A telegram came from Von Habsburg at Vienna whilst I was at dinner, suggesting that I should be at [ILLEGIBLE] tonight, as it might be well to be at hand, and stating that he was leaving by the night mail and would join me early in the morning.9 September.

I was pretty tired and worn out when I got to [ILLEGIBLE]. For two nights I had hardly had a wink of sleep, and my brain was beginning to feel that numbness which marks cerebral exhaustion. Loukia was up and in cheerful spirits. When she shook hands with me she looked sharply in my face and said,

“No sitting up tonight for you. You are worn out. I am quite well again. Indeed, I am, and if there is to be any sitting up, it is I who will sit up with you.”

I would not argue the point, but went and had my supper. Lucy came with me, and, enlivened by her charming presence, I made an excellent meal, and had a couple of glasses of the more than excellent port. Then Lucy took me upstairs, and showed me a room next her own, where a cozy fire was burning.

“Now,” she said. “You must stay here. I shall leave this door open and my door too. You can lie on the sofa for I know that nothing would induce any of you doctors to go to bed whilst there is a patient above the horizon. If I want anything I shall call out, and you can come to me at once.”

I could not but acquiesce, for I was dog tired, and could not have sat up had I tried. So, on her renewing her promise to call me if she should want anything, I lay on the sofa, and forgot all about everything.Loukia Este-Ravenna’s Diary

9 September.I feel so happy tonight. I have been so miserably weak, that to be able to think and move about is like feeling sunshine after a long spell of east wind out of a steel sky. Somehow Michael feels very, very close to me. I seem to feel his presence warm about me. I suppose it is that sickness and weakness are selfish things and turn our inner eyes and sympathy on ourselves, whilst health and strength give love rein, and in thought and feeling he can wander where he wills. I know where my thoughts are. If only Michael knew! My dear, my dear, your ears must tingle as you sleep, as mine do waking. Oh, the blissful rest of last night! How I slept, with that dear, good Dr. Stavridis watching me. And tonight I shall not fear to sleep, since he is close at hand and within call. Thank everybody for being so good to me. Thank God! Goodnight Michael.

Dr. Stavridis’s Diary

10 September.I was conscious of the Professor’s hand on my head, and started awake all in a second. That is one of the things that we learn in an asylum, at any rate.

“Und how ist our patient?”

“Well, when I left her, or rather when she left me,” I answered.

“Come, let us see,” he said. And together we went into the room.

The blind was down, and I went over to raise it gently, whilst Van Helsing stepped, with his soft, cat-like tread, over to the bed.

As I raised the blind, and the morning sunlight flooded the room, I heard the Professor’s low hiss of inspiration, and knowing its rarity, a deadly fear shot through my heart. As I passed over he moved back, and his exclamation of horror, “Gott in Himmel! [sic]” needed no enforcement from his agonized face. He raised his hand and pointed to the bed, and his iron face was drawn and ashen white. I felt my knees begin to tremble.

There on the bed, seemingly in a swoon, lay poor Loukia, more horribly white and wan-looking than ever. Even the lips were white, and the gums seemed to have shrunken back from the teeth, as we sometimes see in a corpse after a prolonged illness.

Von Habsburg raised his foot to stamp in anger, but the instinct of his life and all the long years of habit stood to him, and he put it down again softly.

“Schnell!” he said. “Bring zhe beer.”

I flew to the dining room, and returned with the decanter. He wetted the poor white lips with it, and together we rubbed palm and wrist and heart. He felt her heart, and after a few moments of agonizing suspense said,

“It ist nicht too late. It beats, zhough but feebly. All our vork ist undone. Ve must begin again. Zhere ist no young Michael here now. Ich have to call on du yourself zhis time, friend John.” As he spoke, he was dipping into his bag, and producing the instruments of transfusion. I had taken off my coat and rolled up my shirt sleeve. There was no possibility of an opiate just at present, and no need of one. and so, without a moment’s delay, we began the operation.

After a time, it did not seem a short time either, for the draining away of one’s blood, no matter how willingly it be given, is a terrible feeling, Von Habsburg held up a warning finger. “Do nicht stir,” he said. “But Ich fear zhat vith growing strength she may vake, und zhat vould make danger, oh, so much danger. But Ich shall precaution take. Ich shall give hypodermic injection of morphia.” He proceeded then, swiftly and deftly, to carry out his intent.

The effect on Loukia was not bad, for the faint seemed to merge subtly into the narcotic sleep. It was with a feeling of personal pride that I could see a faint tinge of color steal back into the pallid cheeks and lips. No man knows, till he experiences it, what it is to feel his own lifeblood drawn away into the veins of the woman he loves.

The Professor watched me critically. “Zhat vill do,” he said. “Already?” I remonstrated. “You took a great deal more from Mike.” To which he smiled a sad sort of smile as he replied,

“He ist her lover, her fiance. Du have work, much work to do for her and for others, and the present will suffice.”

When we stopped the operation, he attended to Lucy, whilst I applied digital pressure to my own incision. I laid down, while I waited his leisure to attend to me, for I felt faint and a little sick. By and by he bound up my wound, and sent me downstairs to get a glass of wine for myself.

I had done my part, and now my next duty was to keep up my strength. I felt very weak, and in the weakness lost something of the amazement at what had occurred. I fell asleep on the sofa, however, wondering over and over again how Loukia had made such a retrograde movement, and how she could have been drained of so much blood with no sign any where to show for it. I think I must have continued my wonder in my dreams, for, sleeping and waking my thoughts always came back to the little punctures in her throat and the ragged, exhausted appearance of their edges, tiny though they were.

Loukia slept well into the day, and when she woke she was fairly well and strong, though not nearly so much so as the day before.

She chatted with me freely, and seemed quite unconscious that anything had happened. I tried to keep her amused and interested. When her mother came up to see her, she did not seem to notice any change whatever, but said to me gratefully,

“We owe you so much, Dr. Stavridis, for all you have done, but you really must now take care not to overwork yourself. You are looking pale yourself. You want a wife to nurse and look after you a bit, that you do!” As she spoke, Loukia turned crimson, though it was only momentarily, for her poor wasted veins could not stand for long an unwonted drain to the head. The reaction came in excessive pallor as she turned imploring eyes on me. I smiled and nodded, and laid my finger on my lips. With a sigh, she sank back amid her pillows. Von Habsburg returned in a couple of hours, and presently said to me. “Now you go home, and eat much and drink enough. Make yourself strong. I stay here tonight, and I shall sit up with little miss myself. You and I must watch the case, and we must have none other to know. I have grave reasons. No, do not ask the. Think what you will. Do not fear to think even the most not-improbable. Goodnight.”

In the hall two of the maids came to me, and asked if they or either of them might not sit up with Miss Lucy. They implored me to let them, and when I said it was Dr. Von Habsburg’s wish that either he or I should sit up, they asked me quite piteously to intercede with the’foreign gentleman’. I was much touched by their kindness. Perhaps it is because I am weak at present, and perhaps because it was on Loukia’s account, that their devotion was manifested. For over and over again have I seen similar instances of woman’s kindness. I got back here in time for a late dinner, went my rounds, all well, and set this down whilst waiting for sleep. It is coming.11 September.

This afternoon I went over again. Found Von Habsburg in excellent spirits, and Lucy much better. Shortly after I had arrived, a big parcel from abroad came for the Professor. He opened it with much impressment, assumed, of course, and showed a great bundle of white flowers.

“These are for you, Frau Loukia,” he said.

“For me? Oh, Dr. Von Habsburg!”

“Ja, but zhese are medicines.” Here Loukia made a wry face. “Zhis is medicinal, but du do nicht know how. Ich put him in your vindow, Ich make pretty vreath, and hang him round your neck, so du sleep vell. Ja! Zhey, like zhe lotus flower, make your trouble forgotten. It smell so like zhe vaters of Lethe, and of zhat fountain of youth that the Conquistadores sought for, and find him all too late.”

Whilst he was speaking, Loukia had been examining the flowers and smelling them. Now she threw them down saying, with half laughter, and half disgust,

“Oh, Professor, I believe you are only putting up a joke on me. Why, these flowers are only common garlic.”

To my surprise, Von Habsburg rose up and said with all his sternness, his iron jaw set and his bushy eyebrows meeting,

“Ich bin very serious! Zhere ist a reason Ich do zhis!”

We went into the room, taking the flowers with us. The Professor’s actions were certainly odd and not to be found in any pharmacopeia that I ever heard of. First he fastened up the windows and latched them securely. Next, taking a handful of the flowers, he rubbed them all over the sashes, as though to ensure that every whiff of air that might get in would be laden with the garlic smell. Then with the wisp he rubbed all over the jamb of the door, above, below, and at each side, and round the fireplace in the same way. It all seemed grotesque to me, and presently I said, “Well, Professor, I know you always have a reason for what you do, but this certainly puzzles me. It is well we have no sceptic here, or he would say that you were working some spell to keep out an evil spirit.”

“Perhaps Ich am!” He answered quietly as he began to make the wreath which Lucy was to wear round her neck.

We then waited whilst Loukia made her toilet for the night, and when she was in bed he came and himself fixed the wreath of garlic round her neck. The last words he said to her were,

“Take care you do nicht disturb it, und even if zhe room feel close, do nicht tonight open zhe window or zhe door.”

“I promise,” said Loukia. “And thank you both a thousand times for all your kindness to me! Oh, what have I done to be blessed with such friends?”

As we left the house in my fly, which was waiting, Von Habsburg said,”Tonight Ich kann sleep in peace, and sleep Ich vant, two nights of travel, much reading in zhe day between, und much anxiety on zhe day to follow, and a night to sit up, vithout to vink. Tomorrow in the morning early du call for mich, und ve come together to see our pretty frau, so much more strong for mein ‘spell’ vhich Ich have vork. Ho, ho!”

He seemed so confident that I, remembering my own confidence two nights before and with the baneful result, felt awe and vague terror. It must have been my weakness that made me hesitate to tell it to my friend, but I felt it all the more, like unshed tears.

((To All)

“Apologies for my absence in recent meetings Senators the recent unrest within the Empire has been particularly harsh towards me and my family recently. Many in my family serve in her Majesty’s government and armed forces and regretfully several were killed. These events, while comparable to nothing less than treason, do nonetheless prompt us all to reflect on the current conditions of everyone in the Empire especially labourers, farmers and other such poorer and less educated members of our society. While I am no socialist I believe that all individuals have a duty to help those in need and as such mayhaps from these great halls we ourselves might move to help those deserving of aid?Another point that may be of interest to note is that in my capacity as Governor of Reatia I was left in charge of defending the province from these traitors. While the land and its people escaped the worst of the violence some concerning discoveries were made. In the dying days of the revolt rumors began to spread of Hungarian and German involvement in the revolt among the populace. While these wild tales remain precisely that for now the proximity of Reatia to both these nations has prompted no small concern and arguably even panic in those of a more nervous disposition. Whatever the rumor what cannot be ignored is that some of the weapons found in the hands of these traitors are beyond doubt models used by the Hungarian and German militaries. I must ask that the Ministers for Security and Intelligence examine these concerns without delay!”

((Internally))

Oh no not another one

A senate page had just handed our kilted senator yet another telegram from his nephew Alexandros further expanding his apparent exploits in fighting the revolt with the imperial cavalry in Britannia after being pushed through the military school early owning to a need to fill the ranks. Apparently Alaxandros had made quite a name for himself along with this new found friend of his a chap named Winston who was seemingly a relation of the Duke of Marlborough.

A senator garbed a loose piece of paper quickly scribbled a note and handed it to the nearest page with the words “have that cabled immediately.”- Senator Comminus

Thank you for bringing up the matter of the German-Hungarian weaponry. We can now assume that Angelos is fleeing towards Germany or Hungary, and I will advise the General Staff to deploy the correct legions to intercept him. I also advise the Foreign Ministry to bring up this matter with the German and Hungarian governments.

- Senator Doukas, Minister of Security

The Address

Senators,

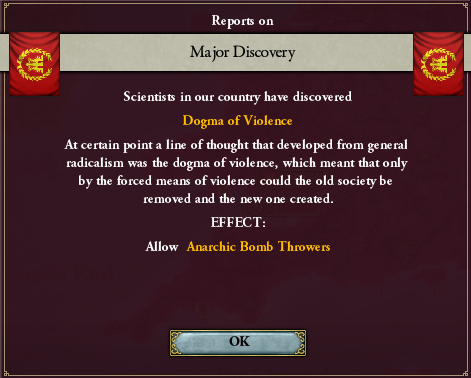

1890 began with a small rebellion in Wales. They were swiftly dispersed, but they were a harbinger of a new dogma of violence.

Beginning in March, We attempted to regain control of the economy. Coal shortages were preventing the creation of cement, so We forcibly closed the smaller glass producers throughout the Empire to attempt to conserve coal. This at least allowed the supplies of cement to increase so that naval base expansion and factory expansion could continue. But the coal shortage did and does continue.

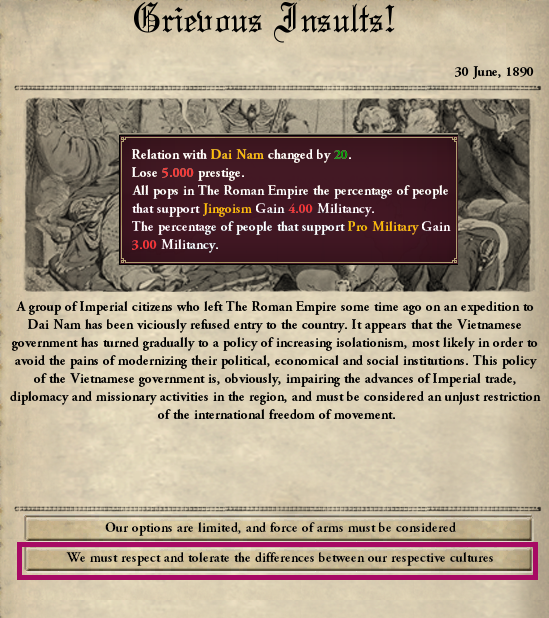

In late June, a visit by Senator Venédiktos Nguyen-Climaco to Dia Nam was canceled when they refused to let him into the country. We insisted on a peaceful resolution to the issue, but hotheads throughout the Empire were displeased by this.

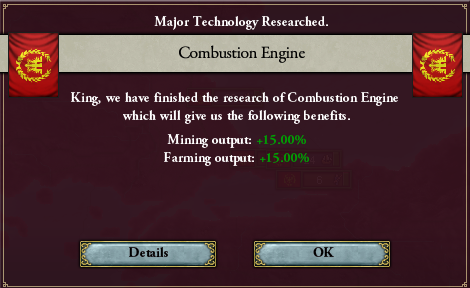

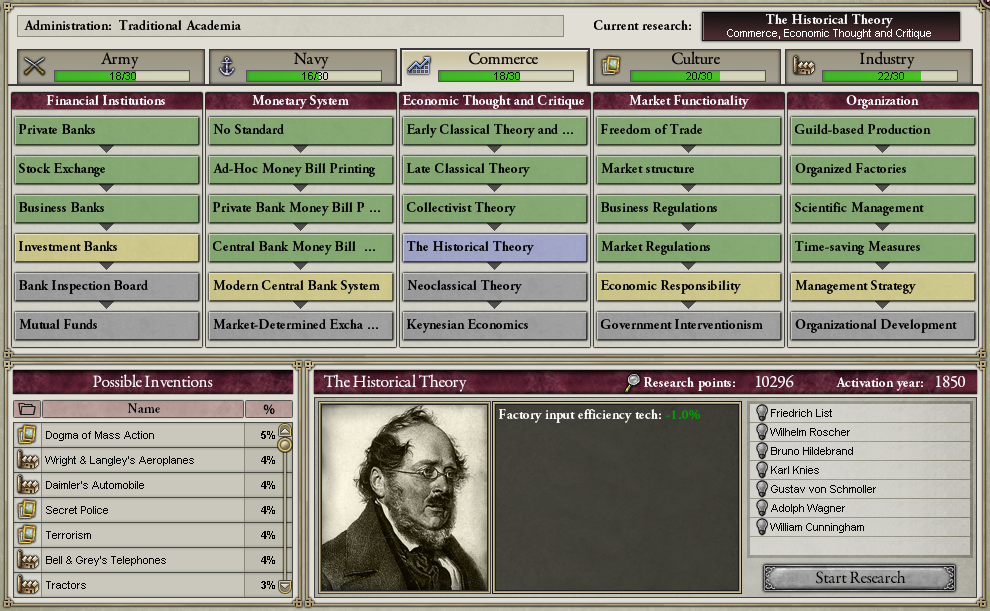

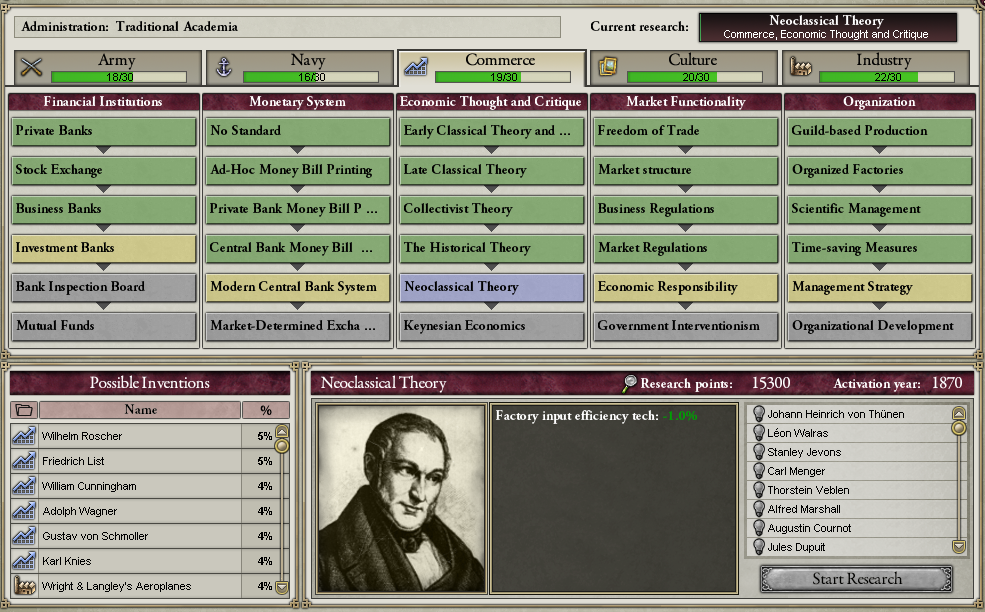

When combustion engines had been sufficiently designed that their development needed no further help, We asked the School of Economics to look through history with an economic mindset to find useful techniques and ideas.

Meanwhile, We began planning to hold a World’s Fair in the Empire.

The beginning of the year demonstrated something to show off at the fair: a system similar to the telegraph, but that allowed one to speak remotely. The inventor called it a telephone, and the name has stuck. As a result, the 1891 World’s Fair was a great success. But later in the year, We saw increasing amount of organization of rebels.

By May the School of Economics had been able to find various efficiencies that left the Empire needing slightly fewer raw materials. We asked them to then use all the tools they had developed in the last fifty years to re-examine the fundamentals of their discipline. Surely more efficiency could be found.

In August, the Communist rebellion we had all feared rose up. But the legions rose to the occasion. By mid-November, all rebels outside of Africa had been put down. But as the communists were whittled down, the nature of the rebellion became more nasty.

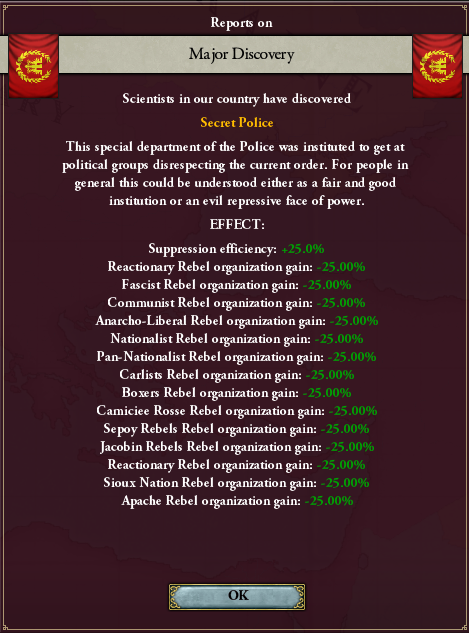

Fortunately, by May of 1892 all rebel forces had been defeated, and it only remained to take back control of any territories they had seized. As the legions did so, We expanded the powers of the Minister of Security in order to prevent such uprisings in the future.

In the midst of the rebellion, the combustion engine was applied in the very down to earth task of farming. It was also applied to a long-held dream of all mankind: flight.

When the School of Economics had reviewed their fundamentals, We had the University of Constantinople create a department of business so that management practices could be researched.

Slightly before the last communist stronghold had been returned to Imperial government, reactionaries rebelled. They were swiftly put down by the end of February, while the communist rebels had been finished mid-January.

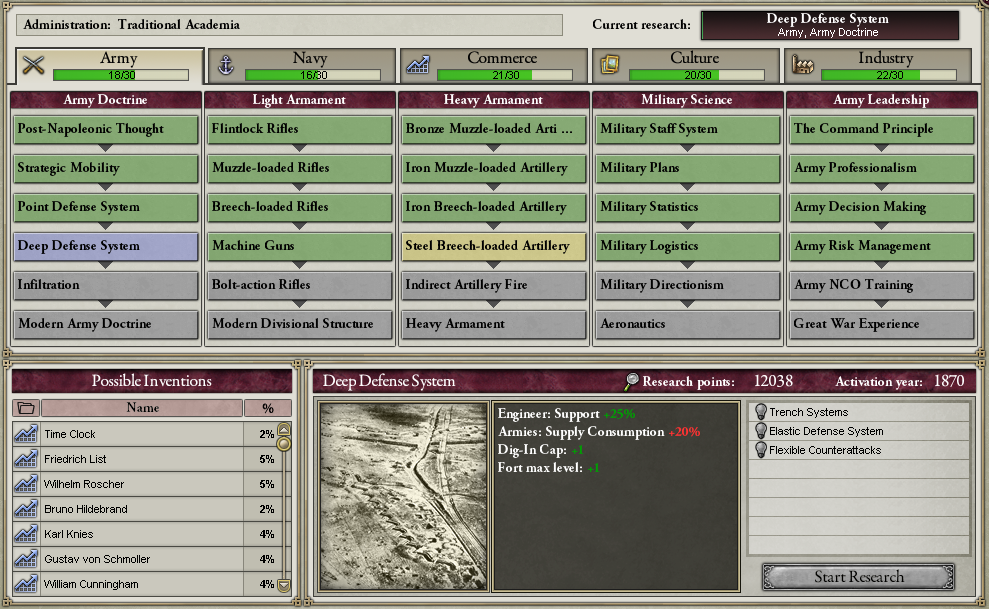

With the founding of the School of Business, We instructed the legions to implement some ideas they had been sharing: that of having several layers of defense in order to better stop the enemy.

Meanwhile, Japan declared war on Korea to reconquer Pyongyang, and asked Us to assist them. We would have preferred to see a fully independent Korea, but it was clear that they would lose regardless, so We agreed in order to keep Our alliance with Japan. Soon enough, Japan asked Us to witness the signing of their peace treaty.

The news that We had been agitating for the handover of Sulu from Hedjaz inspired another communist revolt in March of 1893.

While this one was more easily put down, before it was finished off, Jacobins were inspired by Austria’s creation of a radical democracy and rose up. They had somehow not noticed that Austria was too weak to fend off Scandinavia and was about to be annexed.

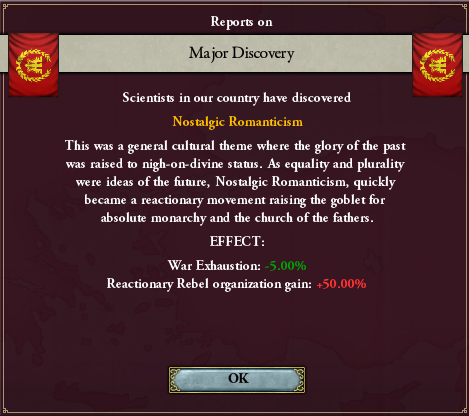

This led the more reactionary elements of the Empire to wistfully reminisce about the times before all these rebellions, likewise failing to notice an important detail: all of the rebellions in the past.

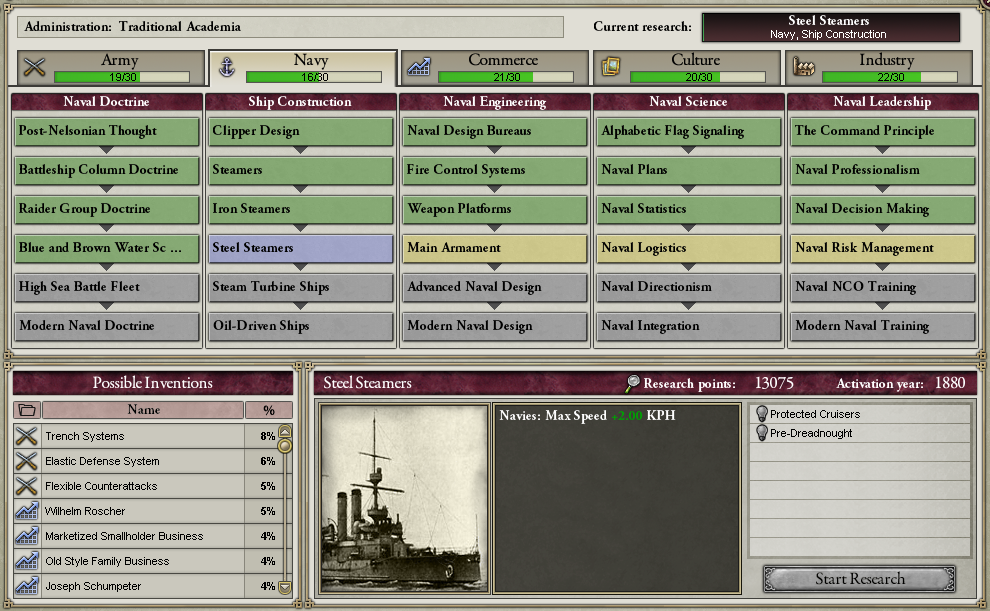

Nevertheless, the rebellion was eventually put down, and the legions developed their systems of deep defenses. We then asked the admiralty to design more modern ships taking advantage of the Empire’s growing stock of high-quality metals.

In February, We declared war on Hedjaz for the last of the Philippine islands. While the land war was perfectly typical, the war on the seas proved that the admiralty was no longer prepared to fight a modern war.

Within days of that battle, however, Hedjaz surrendered and We accepted the peace.

Shortly after the war, the general plans for new ships were ready, though specific designs were still being worked out.

With the end of the war, there had been enough improvement in the economy, and enough money saved, that We began cutting tax rates.

Meanwhile, a citizen began organizing a modern form of the ancient Olympics. We happily agreed to help organize the first Olympics.

In late November 1894, more communist rebels rose up, but it seemed few were willing to use such means any longer. They were defeated just yesterday.

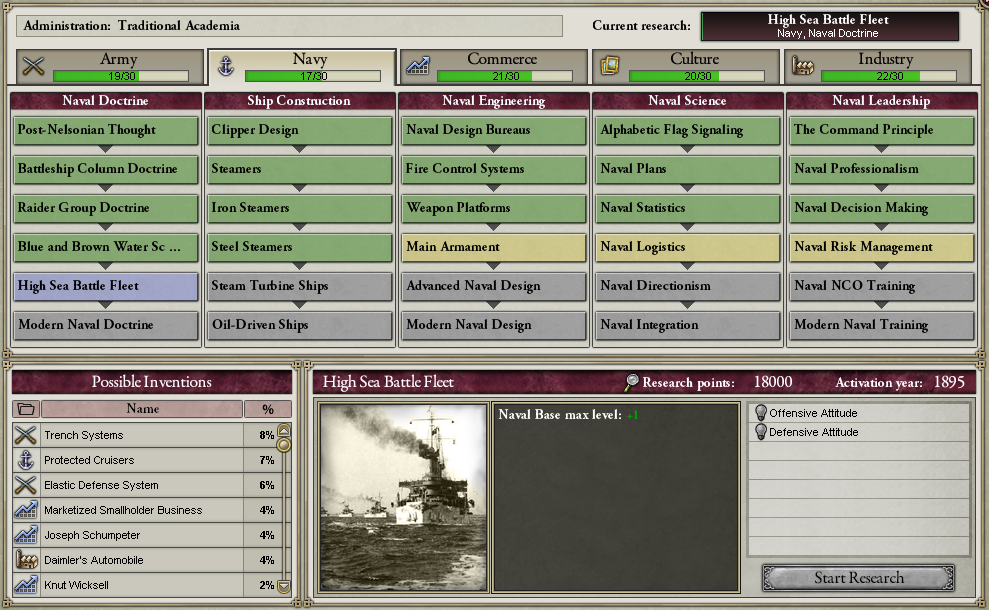

And this morning, We tasked the admiralty with creating the capability to support modern fleets that would not lose as in the last war.

Senators' Replies

Progress moves further onward, especially with the new flying machines we have developed.

Now, as for the Secret Police. Before you jump to conclusions and shout that I am oppressing the common people, allow me to explain. The secret police is controlled by the most senior members of the Ministry of Security, not just me, who make up the Security Council. Any action that the Secret Police takes must first be approved by a majority of these Security Council members to prevent abuse of power. The Empress appoints these members, not me. The Security Council is evenly divided into groups of conservatives, liberals, and socialists so that each group gains representation and no single group may use the Secret Police for its own agenda.

In the imperial edict establishing the Secret Police, several limitations have been put on the Secret Police (which can be extended or revoked by the Empress alone at will). First, the Secret Police may not be used to crack down on peaceful protests without a credible reason. Second, the Secret Police must have a credible reason to arrest a person. Personal motives do not count as credible reasons. Third, the Secret Police was created to prevent future militant uprisings against the State and shall primarily focus on that goal. So the Secret Police, for example, is obliged to find and capture Markos Angelos but is forbidden from arresting citizens without a credible reason such as evidence of an imminent rebellion. Fourth, senators are immune from investigation by the Secret Police but are not immune to investigation by regular police forces.I assure you, the Secret Police is not an extension of my personal power but merely a necessity to maintain order in the Empire. We must be prepared to sacrifice a few liberties in favor of stability. The Secret Police will weaken if not prevent the formation of rebellions while trying to prevent abuses of the common people. If I find out that any member of the Secret Police has been abusing their power to mistreat citizens, he will be dismissed from service immediately.

-Doukas

Communists! How dare they rise up against the Empress’ magnanimity! We will crush them with impunity! As long as militant Communists exist, we will hunt them down and destroy down just as like how we hunted down the Cult! Also, the fact that a minor nation was able to crush our Imperial Fleet is worrying. We must modernize before a major naval power engages us and destroys our fleet!

- Senator Palaiologos

Perhaps we could make use of our new flying machines in order to assist our troops and fleets in the future? Think about it: the aeroplanes can provide reconnaissance and possibly drop bombs on our enemy well before they even reach our lines or our ships! As long as we maintain a monopoly on them victory in battle is assured.

- Senator Doukas

Senators I will not comment on the secret police, I feel that discussing this group outside of the Security Council would not be in the best interests of the nation.

I can only implore the Senate and the Empress to look to provide more political and social support to the people to help us reduce the threat from hotheads within our ranks causing these issue.

More importantly for an empire as far fung as our own how is it possible that we have allowed our fleet to be reduced to such a state, is there any response from the Naval Office?

- Senator Gray

Greetings Senators! I have returned from Australia and I am pleased to report its industrialization is going along swimmingly. Now, to subjects you may be concerned about. The ministry of Armaments more than ecstatic to begin working on new warships for the Imperial fleet, particularly these “Pre-Dreadnoughts” and “Dreadnoughts”. Secondly, I wish my ministry had known sooner about the developments of these “telephones”; while they are amazing feats of modern engineering, we believe the military should have had access to it first before the civilian population, seeing as now not only can rebels and terror cells interact instantly, but that we cannot communicate faster and more reliably with ourselves than they can. Finally, I am very content on the formation of the secret police, I believe it will bring overall great peace and destroy dissidents before it even begins. The Ministry of Armaments fully supports the secret police and hopes to work together with them in the future to support the security of the empire.

- Senator Magnus Kvensson

Determining Positions

Senators, thank you for your replies. We are glad of the organization Senator Doukas developed for the Secret Police. We would not wish them to become a tool of tyranny. And We agree at the need to modernize the navy. If any Senators have concrete proposals for how to do so, We would hear them.

As well, We wish to reconsider the policy of automatically renewing governorships and ministries. We do not wish them to be as the old feudal offices. So We shall open all governorships and ministries to all Senators, barring Thracia, which remains under the governorship of the royal family. Therefore, these are the governorships available:

(North) Africa

Armenia

Asia

Britannia

Dalmatia

Egypt

Georgia

Guayana

Macedonia

Mauretania

Naples

Palestine

Raetia

Sicily

Syria

Aquitaine (Aquitaine peoples)

Australia

Azerbaijan (Azerbaijani peoples)

Belgium (Flemish and Walloon peoples)

Brittany (Breton peoples)

Burgundy (Burgundian peoples)

Catalonia (Andalucian peoples)

France (Cosmopotitaine peoples)

Italy (Italian peoples)

Java (Javan peoples)

New Zealand

Philippines (Filipino peoples)

South Africa

Spain (Castilian and Andalusian peoples)

Wales (Welsh peoples)

Which regions would the Senators prefer to govern? If there are conflicting desires, We shall make the necessary decisions. And these are the available ministries:

Foreign minister

Armament minister

Minister of security

Minister of intelligence

Chief of Staff

Chief of the Army

Chief of the Navy

Again, if there are conflicting desires, We shall make the necessary decisions.

Senators' Requests

I wish to continue serving as governor of Italy, for it is my home and my people. I will gladly continue as Minister of Intelligence if required, but Foreign Minister would be a preferable alternative.

- Senator Leonardo Favero

I would like to resume the governorship of Britannia.

- Senator Palaiologos

I wish to continue my serving as Minister of Security. I would be fine with governing Macedonia, but Palestine would also be acceptable.

- Senator Doukas

I rely on you Empress to choose. I can resume my work as governor of (North) Africa, or move to governorships that are more in need of being represented by Senator in Senate.

- Senator Alexandros Damaskinos

Alexios says, “the fortunes of House Angelos are invested in Thessaloniki, so I would wish to continue my father’s legacy in Macedonia. I trust that we have not offended the Basilissa such that she would pass us over for another house.” He looks pointedly at Michael Doukas.

Regarding the Angeloi’s desire to continue their governorship of Macedonia, I have no objections, and I shall humbly retract my request to become governor of Macedonia. I am now in favor of becoming governor of either Palestine or Syria.

- Senator Doukas

I ask if the Empress might consider consolidating some of the governorship’s of the Indonesia, Australasia and Pacific Island territories into one larger governorship of Oceania Major. Baring the Philippines of course. I also ask that I be the Governor of this new provence, but if that cannot be achieved, then I ask for my former position as governor of Australia.

- Senator Kvensson

After seeking a plebiscite in Brittany, the people have endorsed my continued governship if it pleases your majesty.

I am happy to maintain my role as COS, however if another senator feels that this position would suit them better I will reliquish the role to maintain balance and order in the Senate.

- Senator Gray

((private))

Loukia Este-Ravenna’s Diary

12 September.How good they all are to me. I quite love that dear Dr. Von Habsburg. I wonder why he was so anxious about these flowers. He positively frightened me, he was so fierce. And yet he must have been right, for I feel comfort from them already. Somehow, I do not dread being alone tonight, and I can go to sleep without fear. I shall not mind any flapping outside the window. Oh, the terrible struggle that I have had against sleep so often of late, the pain of sleeplessness, or the pain of the fear of sleep, and with such unknown horrors as it has for me! How blessed are some people, whose lives have no fears, no dreads, to whom sleep is a blessing that comes nightly, and brings nothing but sweet dreams. Well, here I am tonight, hoping for sleep, and lying like Ophelia in the play, with’virgin crants and maiden strewments.’ I never liked garlic before, but tonight it is delightful! There is peace in its smell. I feel sleep coming already. Goodnight, everybody.

Dr. Stavridis’s Diary

13 September.Called and found Van Helsing, as usual, up to time. The carriage ordered from the hotel was waiting. The Professor took his bag, which he always brings with him now.

Let all be put down exactly. Von Habsburg and I arrived at eight o’clock. It was a lovely morning. The bright sunshine and all the fresh feeling of early autumn seemed like the completion of nature’s annual work. The leaves were turning to all kinds of beautiful colors, but had not yet begun to drop from the trees. When we entered we met Mrs. Este-Ravenna coming out of the morning room. She is always an early riser. She greeted us warmly and said,

“You will be glad to know that Loukia is better. The dear child is still asleep. I looked into her room and saw her, but did not go in, lest I should disturb her.” The Professor smiled, and looked quite jubilant. He rubbed his hands together, and said, “Aha! Ich zhought Ich had diagnosed zhe case. Mein treatment ist vorking.”

To which she replied, “You must not take all the credit to yourself, doctor. Lucy’s state this morning is due in part to me.”

“How do du mean, ma’am?” asked the Professor.

“Well, I was anxious about the dear child in the night, and went into her room. She was sleeping soundly, so soundly that even my coming did not wake her. But the room was awfully stuffy. There were a lot of those horrible, strongsmelling flowers about everywhere, and she had actually a bunch of them round her neck. I feared that the heavy odor would be too much for the dear child in her weak state, so I took them all away and opened a bit of the window to let in a little fresh air. You will be pleased with her, I am sure.”

She moved off into her boudoir, where she usually breakfasted early. As she had spoken, I watched the Professor’s face, and saw it turn ashen gray. He had been able to retain his self-command whilst the poor lady was present, for he knew her state and how mischievous a shock would be. He actually smiled on her as he held open the door for her to pass into her room. But the instant she had disappeared he pulled me, suddenly and forcibly, into the dining room and closed the door.

Then, for the first time in my life, I saw Von Habsburg break down. He raised his hands over his head in a sort of mute despair, and then beat his palms together in a helpless way. Finally he sat down on a chair, and putting his hands before his face, began to sob, with loud, dry sobs that seemed to come from the very racking of his heart. He began to put effort on his Greek, to eliminate the German influences in his speech.

Then he raised his arms again, as though appealing to the whole universe. “Gott! Gott! Gott!” he said. “Vhat have ve done, vhat has zhis poor zhing done, zhat ve are so sore beset? Ist zhere fate amongst us still, send down from the pagan world of old, that such things must be, and in such way? This poor mother, all unknowing, and all for the best as she think, does such thing as lose her daughter body and soul, and we must not tell her, we must not even warn her, or she die, then both die. Oh, how we are beset! How are all the powers of the devils against us!”

Suddenly he jumped to his feet. “Come,” he said.”come, we must see and act. Devils or no devils, or all the devils at once, it matters not. We must fight him all the same.” He went to the hall door for his bag, and together we went up to Loukia’s room.

Once again I drew up the blind, whilst Von Habsburg went towards the bed. This time he did not start as he looked on the poor face with the same awful, waxen pallor as before. He wore a look of stern sadness and infinite pity.

“As I expected,” he murmured, with that hissing inspiration of his which meant so much. Without a word he went and locked the door, and then began to set out on the little table the instruments for yet another operation of transfusion of blood. I had long ago recognized the necessity, and begun to take off my coat, but he stopped me with a warning hand. “No!” he said. “Today you must operate. I shall provide. You are weakened already.” As he spoke he took off his coat and rolled up his shirtsleeve.

Again the operation. Again the narcotic. Again some return of color to the ashy cheeks, and the regular breathing of healthy sleep. This time I watched whilst Von Habsburg recruited himself and rested.

Presently he took an opportunity of telling Mrs. Este-Ravenna that she must not remove anything from Loukia’s room without consulting him. That the flowers were of medicinal value, and that the breathing of their odor was a part of the system of cure. Then he took over the care of the case himself, saying that he would watch this night and the next, and would send me word when to come.

After another hour Loukia waked from her sleep, fresh and bright and seemingly not much the worse for her terrible ordeal.

What does it all mean? I am beginning to wonder if my long habit of life amongst the insane is beginning to tell upon my own brain.Loukia Este-Ravenna’s Diary

17 September.Four days and nights of peace. I am getting so strong again that I hardly know myself. It is as if I had passed through some long nightmare, and had just awakened to see the beautiful sunshine and feel the fresh air of the morning around me. I have a dim half remembrance of long, anxious times of waiting and fearing, darkness in which there was not even the pain of hope to make present distress more poignant. And then long spells of oblivion, and the rising back to life as a diver coming up through a great press of water. Since, however, Dr. Von Habsburg has been with me, all this bad dreaming seems to have passed away. The noises that used to frighten me out of my wits, the flapping against the windows, the distant voices which seemed so close to me, the harsh sounds that came from I know not where and commanded me to do I know not what, have all ceased. I go to bed now without any fear of sleep. I do not even try to keep awake. I have grown quite fond of the garlic, and a boxful arrives for me every day Tonight Dr. Von Habsburg is going away, as he has to be for a day in Vienna. But I need not be watched. I am well enough to be left alone.

Thank God for Mother’s sake, and dear Michael’s, and for all our friends who have been so kind! I shall not even feel the change, for last night Dr. Von Habsburg slept in his chair a lot of the time. I found him asleep twice when I awoke. But I did not fear to go to sleep again, although the boughs or bats or something flapped almost angrily against the window panes.The Mall Gazette, 18 September.

THE ESCAPED WOLF PERILOUS ADVENTURE OF OUR INTERVIEWERINTERVIEW WITH THE KEEPER IN THE ZOOLOGICAL GARDENS

After many inquiries and almost as many refusals, and perpetually using the words ‘MALL GAZETTE ‘ as a sort of talisman, I managed to find the keeper of the section of the Zoological Gardens in which the wolf department is included. Thomas Bilder, an immigrant from Britannia, lives in one of the cottages in the enclosure behind the elephant house, and was just sitting down to his tea when I found him. Thomas and his wife are hospitable folk, elderly, and without children, and if the specimen I enjoyed of their hospitality be of the average kind, their lives must be pretty comfortable. The keeper would not enter on what he called business until the supper was over, and we were all satisfied. Then when the table was cleared, and he had lit his pipe, he said,“Now, Sir, you can go on and arsk me what you want. You’ll excoose me refoosin’ to talk of perfeshunal subjucts afore meals. I gives the wolves and the jackals and the hyenas in all our section their tea afore I begins to arsk them questions.”

“How do you mean, ask them questions?” I queried, wishful to get him into a talkative humor.

” ‘Ittin’ of them over the ‘ead with a pole is one way. Scratchin’ of their ears in another, when gents as is flush wants a bit of a show-orf to their gals. I don’t so much mind the fust, the ‘ittin of the pole part afore I chucks in their dinner, but I waits till they’ve ‘ad their sherry and kawffee, so to speak,afore I tries on with the ear scratchin’. Mind you,” he added philosophically, “there’s a deal of the same nature in us as in them theer animiles. Here’s you a-comin’ and arskin’ of me questions about my business, and I that grump-like that only for your bloomin’ ‘arf-quid I’d ‘a’ seen you blowed fust ‘fore I’d answer. Not even when you arsked me sarcastic like if I’d like you to arsk the Superintendent if you might arsk me questions. Without offence did I tell yer to go to ‘ell?”

“You did.”

“An’ when you said you’d report me for usin’ obscene language that was ‘ittin’ me over the ‘ead. But the ‘arfquid made that all right. I weren’t a-goin’ to fight, so I waited for the food, and did with my ‘owl as the wolves and lions and tigers does. But, lor’ love yer ‘art, now that the old ‘ooman has stuck a chunk of her tea-cake in me, an’ rinsed me out with her bloomin’ old teapot, and I’ve lit hup, you may scratch my ears for all you’re worth, and won’t even get a growl out of me. Drive along with your questions. I know what yer a-comin’ at, that ‘ere escaped wolf.”

“Exactly. I want you to give me your view of it. Just tell me how it happened, and when I know the facts I’ll get you to say what you consider was the cause of it, and how you think the whole affair will end.”

“All right, guv’nor. This ‘ere is about the ‘ole story. That’ere wolf what we called Bersicker was one of three gray ones that came from Norway to Jamrach’s, which we bought off him four years ago. He was a nice well-behaved wolf, that never gave no trouble to talk of. I’m more surprised at ‘im for wantin’ to get out nor any other animile in the place. But, there, you can’t trust wolves no more nor women.”

“Don’t you mind him, Sir!” broke in Mrs. Tom, with a cheery laugh. “ ‘E’s got mindin’ the animiles so long that blest if he ain’t like a old wolf ‘isself! But there ain’t no ‘arm in ‘im.”

“Well, Sir, it was about two hours after feedin’ yesterday when I first hear my disturbance. I was makin’ up a litter in the monkey house for a young puma which is ill. But when I heard the yelpin’ and ‘owlin’ I kem away straight. There was Bersicker a-tearin’ like a mad thing at the bars as if he wanted to get out. There wasn’t much people about that day, and close at hand was only one man, a tall, thin chap, with a ‘ook nose and a pointed beard, with a few white hairs runnin’ through it. He had a ‘ard, cold look and red eyes, and I took a sort of mislike to him, for it seemed as if it was ‘im as they was hirritated at. He ‘ad white kid gloves on ‘is ‘ands, and he pointed out the animiles to me and says, ‘Keeper, these wolves seem upset at something.’

“‘Maybe it’s you,’ says I, for I did not like the airs as he give ‘isself. He didn’t get angry, as I ‘oped he would, but he smiled a kind of insolent smile, with a mouth full of white, sharp teeth. ‘Oh no, they wouldn’t like me,’ ‘e says.

” ‘Ow yes, they would,’ says I, a-imitatin’of him.’They always like a bone or two to clean their teeth on about tea time, which you ‘as a bagful.’

“Well, it was a odd thing, but when the animiles see us a-talkin’ they lay down, and when I went over to Bersicker he let me stroke his ears same as ever. That there man kem over, and blessed but if he didn’t put in his hand and stroke the old wolf’s ears too!

” ‘Tyke care,’ says I. ‘Bersicker is quick.’

” ‘Never mind,’ he says. I’m used to ‘em!’

” ‘Are you in the business yourself?”I says, tyking off my ‘at, for a man what trades in wolves, anceterer, is a good friend to keepers.

” ‘Nom’ says he, ‘not exactly in the business, but I ‘ave made pets of several.’ and with that he lifts his ‘at as perlite as a lord, and walks away. Old Bersicker kep’ a-lookin’ arter ‘im till ‘e was out of sight, and then went and lay down in a corner and wouldn’t come hout the ‘ole hevening. Well, larst night, so soon as the moon was hup, the wolves here all began a-‘owling. There warn’t nothing for them to ‘owl at. There warn’t no one near, except some one that was evidently a-callin’ a dog somewheres out back of the gardings in the Park road. Once or twice I went out to see that all was right, and it was, and then the ‘owling stopped. Just before twelve o’clock I just took a look round afore turnin’ in, an’, bust me, but when I kem opposite to old Bersicker’s cage I see the rails broken and twisted about and the cage empty. And that’s all I know for certing.”

“Did any one else see anything?”

“One of our gard’ners was a-comin’ ‘ome about that time from a ‘armony, when he sees a big gray dog comin’ out through the garding ‘edges. At least, so he says, but I don’t give much for it myself, for if he did ‘e never said a word about it to his missis when ‘e got ‘ome, and it was only after the escape of the wolf was made known, and we had been up all night a-huntin’ of the Park for Bersicker, that he remembered seein’ anything. My own belief was that the ‘armony ‘ad got into his ‘ead.”

“Now, Mr. Bilder, can you account in any way for the escape of the wolf?”

“Well, Sir,”he said, with a suspicious sort of modesty, “I think I can, but I don’t know as ‘ow you’d be satisfied with the theory.”

“Certainly I shall. If a man like you, who knows the animals from experience, can’t hazard a good guess at any rate, who is even to try?”

“well then, Sir, I accounts for it this way. It seems to me that ‘ere wolf escaped–simply because he wanted to get out.”

From the hearty way that both Thomas and his wife laughed at the joke I could see that it had done service before, and that the whole explanation was simply an elaborate sell. I couldn’t cope in badinage with the worthy Thomas, but I thought I knew a surer way to his heart, so I said,”Now, Mr. Bilder, we’ll consider that first half-sovereign worked off, and this brother of his is waiting to be claimed when you’ve told me what you think will happen.”

“Right y’are, Sir,” he said briskly. “Ye’ll excoose me, I know, for a-chaffin’ of ye, but the old woman her winked at me, which was as much as telling me to go on.”

“Well, I never!” said the old lady.

“My opinion is this. That ‘ere wolf is a’idin’ of, somewheres. The gard’ner wot didn’t remember said he was a-gallopin’ northward faster than a horse could go, but I don’t believe him, for, yer see, Sir, wolves don’t gallop no more nor dogs does, they not bein’ built that way. Wolves is fine things in a storybook, and I dessay when they gets in packs and does be chivyin’ somethin’ that’s more afeared than they is they can make a devil of a noise and chop it up, whatever it is. But, Lor’ bless you, in real life a wolf is only a low creature, not half so clever or bold as a good dog, and not half a quarter so much fight in ‘im. This one ain’t been used to fightin’ or even to providin’ for hisself, and more like he’s somewhere round the Park a’hidin’ an’ a’shiverin’ of, and if he thinks at all, wonderin’ where he is to get his breakfast from. Or maybe he’s got down some area and is in a coal cellar. My eye, won’t some cook get a rum start when she sees his green eyes a-shinin’ at her out of the dark! If he can’t get food he’s bound to look for it, and mayhap he may chance to light on a butcher’s shop in time. If he doesn’t, and some nursemaid goes out walkin’ or orf with a soldier, leavin’ of the hinfant in the perambulator–well, then I shouldn’t be surprised if the census is one babby the less. That’s all.”

I was handing him the half-sovereign, when something came bobbing up against the window, and Mr. Bilder’s face doubled its natural length with surprise.

“God bless me!” he said. “If there ain’t old Bersicker come back by ‘isself!”

He went to the door and opened it, a most unnecessary proceeding it seemed to me. I have always thought that a wild animal never looks so well as when some obstacle of pronounced durability is between us. A personal experience has intensified rather than diminished that idea.

After all, however, there is nothing like custom, for neither Bilder nor his wife thought any more of the wolf than I should of a dog. The animal itself was a peaceful and well-behaved as that father of all picture-wolves, Red Riding Hood’s quondam friend, whilst moving her confidence in masquerade.

The whole scene was a unutterable mixture of comedy and pathos. The wicked wolf that for a half a day had paralyzed London and set all the children in town shivering in their shoes, was there in a sort of penitent mood, and was received and petted like a sort of vulpine prodigal son. Old Bilder examined him all over with most tender solicitude, and when he had finished with his penitent said,

“There, I knew the poor old chap would get into some kind of trouble. Didn’t I say it all along? Here’s his head all cut and full of broken glass. ‘E’s been a-gettin’ over some bloomin’ wall or other. It’s a shyme that people are allowed to top their walls with broken bottles. This ‘ere’s what comes of it. Come along, Bersicker.”

He took the wolf and locked him up in a cage, with a piece of meat that satisfied, in quantity at any rate, the elementary conditions of the fatted calf, and went off to report.

I came off too, to report the only exclusive information that is given today regarding the strange escapade at the Zoo.

Dr. Stavridis’s Diary

17 September.I was engaged after dinner in my study posting up my books, which, through press of other work and the many visits to Loukia, had fallen sadly into arrear. Suddenly the door was burst open, and in rushed my patient, with his face distorted with passion. I was thunderstruck, for such a thing as a patient getting of his own accord into the Superintendent’s study is almost unknown.

Without an instant’s notice he made straight at me. He had a dinner knife in his hand, and as I saw he was dangerous, I tried to keep the table between us. He was too quick and too strong for me, however, for before I could get my balance he had struck at me and cut my left wrist rather severely.

Before he could strike again, however, I got in my right hand and he was sprawling on his back on the floor. My wrist bled freely, and quite a little pool trickled on to the carpet. I saw that my friend was not intent on further effort, and occupied myself binding up my wrist, keeping a wary eye on the prostrate figure all the time. When the attendants rushed in, and we turned our attention to him, his employment positively sickened me. He was lying on his belly on the floor licking up, like a dog, the blood which had fallen from my wounded wrist. He was easily secured, and to my surprise, went with the attendants quite placidly, simply repeating over and over again, “The blood is the life! The blood is the life!”

I cannot afford to lose blood just at present. I have lost too much of late for my physical good, and then the prolonged strain of Loukia’s illness and its horrible phases is telling on me. I am over excited and weary, and I need rest, rest, rest. Happily Von Habsburg has not summoned me, so I need not forego my sleep. Tonight I could not well do without it.Telegram, Von Habsburg, Vienna, to Stavridis, Thessalonika

(delivered late by twenty-two hours.)

7 September.

Do not fail to be at Loukia’s tonight. If not watching all the time, frequently visit and see that flowers are as placed, very important, do not fail. Shall be with you as soon as possible after arrival.Dr. Stavridis’s Dieary

18 September.Just off train to Constantinople. The arrival of Von Habsburg’s telegram filled me with dismay. A whole night lost, and I know by bitter experience what may happen in a night. Of course it is possible that all may be well, but what may have happened? Surely there is some horrible doom hanging over us that every possible accident should thwart us in all we try to do. I shall take this cylinder with me, and then I can complete my entry on Loukia’s phonograph.

Memorandum left by Loukia Este-Ravenna

17 September, Night.I write this and leave it to be seen, so that no one may by any chance get into trouble through me. This is an exact record of what took place tonight. I feel I am dying of weakness, and have barely strength to write, but it must be done if I die in the doing.