The Empire Strikes Back 67 - The War of Three Emperors

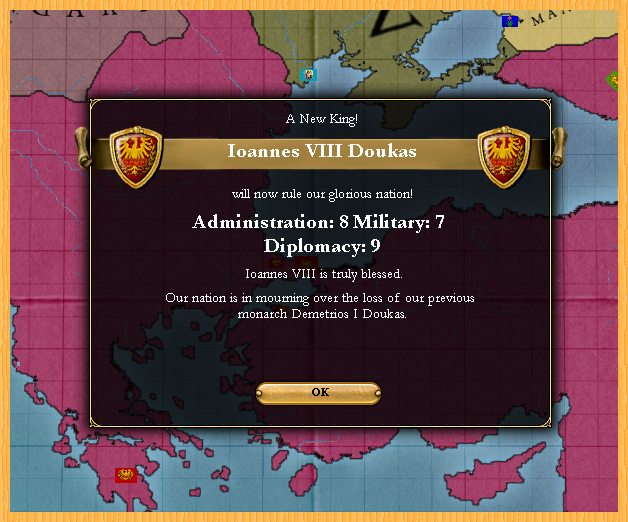

Demetrios I was the son of and successor to Konstantinos the Zealous. He was excellent at war, skilled at diplomacy, and good at administration. His son Ioannes, who promised to be even more skilled, was appointed heir.

Demetrios garnered good will among the nobles when he reestablished parliament. He insisted on appointing the members, but the nobles took this as a sign that they would again have some form of power. They did not see it for the trap it was. However, Demetrios had inherited three wars along with the Empire. His plans to neuter the nobles would have to wait. And wait they did. For he died on March 7th of 1639, Emperor for less than two years.

Ioannes took his place. He was skilled at military matters, a genius at administration and diplomacy, but young and inexperienced. He announced his younger brother Demetrios as heir, and focused on the wars.

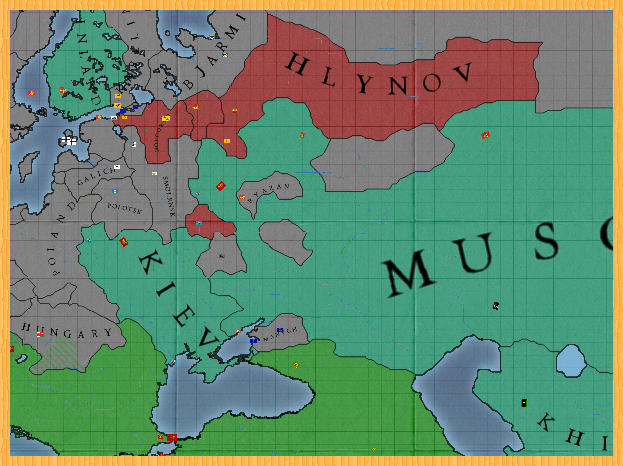

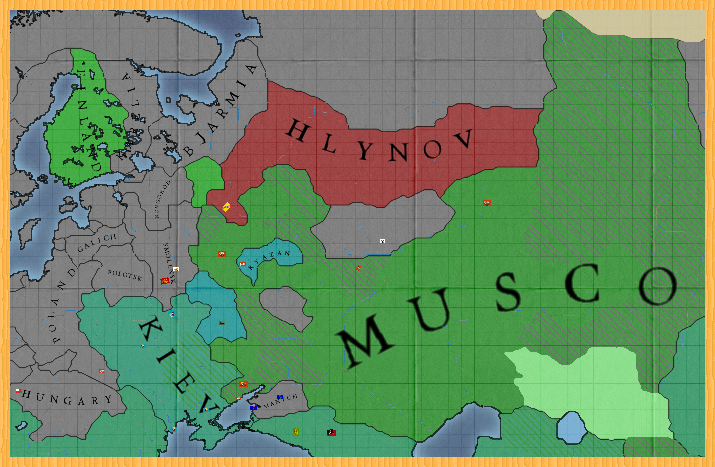

The war in the north had slowly wound in favor of Muscowy. With the Legions’ help, they were able to capture the main cities of the different nations opposing them and force them to surrender, typically with harsh terms. By the time Ioannes came to rule, the war was half over or more.

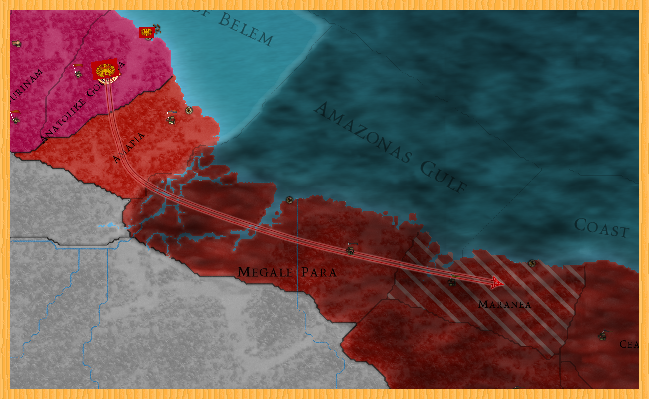

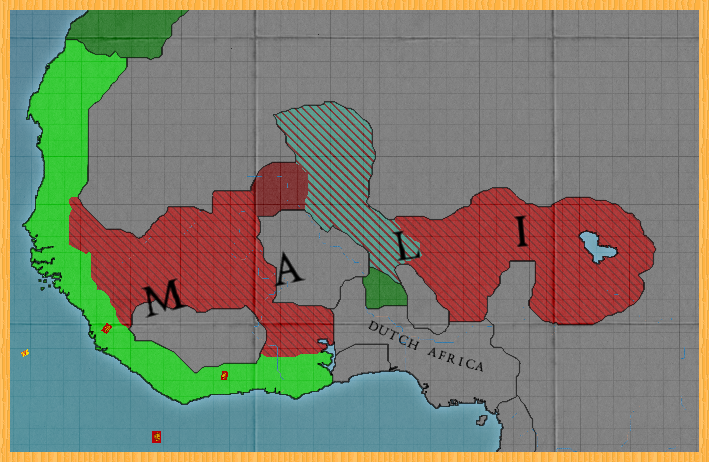

The war against Mali worked more slowly. There were rumors of an army yet unkilled by the Legions, so they did not dare to spread out to besiege the land, and so little territory was just captured. But the Empire was sure to win eventually.

In February of 1640, a routine correspondence with England mentioned that Maranea had been captured by Mali. It was clear that the missing Malinese army was in that region, so XII Legio moved to hunt them down.

By the end of the year, all in the north but Hlynov had surrendered, and even that country was fully occupied. Ioannes made peace with them and left them to Muscowy’s mercies.

While the Mali war still raged, Ioannes implemented reforms of the Imperial mint. The silver stavraton coin was to be replaced by the gold líras. A sample of the minted líras would be stored every year. If the currency was questioned, it could be compared to a standard measure stored by the Emperor. And if the líras at question disagreed with the measure the master of the mint would be punished most severely: castrated, half-hung, and quartered. Thus, the currency could be trusted to not be debased.

And finally in early 1642, Mali was fully defeated. They were forced to give up their coast, their overseas trade now handled by Imperial merchants. Sufficient garrisons were created to keep trade flowing. As well, their central land was returned to a descendant of the Songhai ruling class.

The war, while lasting only five years, was later called the war of three Emperors. While this could have and should have been a satirical reference to the quick succession at this point in time, it became propaganda of the danger and strength of Muslims.