The Empire Strikes Back 65 - The Particularist Revolt

The Imperial colonies had grown greatly in just a few years. This was largely due to the locals. Where the peoples of the Empire expected to “bring civilization to the natives”, the natives proved to be more canny and clever than the incoming settlers. They took advantage of the Imperial technology, adopted Greek as a trade language, and reorganized their localities on their terms. The connection to trans-Atlantic trade was a major boon for them. As was the political organization from the Empire. Those settlers who had dreams of rulership were mostly disappointed. A few rose to prominence, but there was little aristocracy in the colonies. Or at least, the aristocracy was not so formally defined.

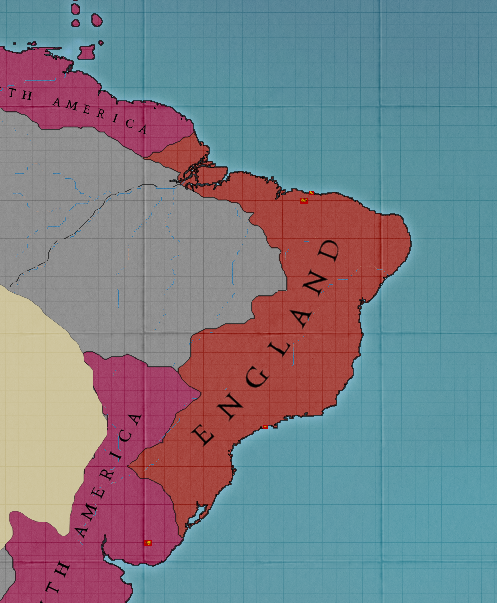

The English colonies were different. The Anglo-Saxons had spent centuries caught between the anvil of Scotland and the hammer of the Empire. When they had the opportunity to leave and form new homes, they remembered their ancestors of a millennia before and took to the sea. The natives in the lands that they occupied swiftly became a lower class. And the English were ravenous for new land.

The political boundaries between the Roman colonies and the English colonies was ill-defined, and the English took advantage of this to keep spreading. Konstantinos sympathized with their desire for a homeland, and so he gave them an offer. Accept the locals as equals, and the entire Brazilian region would go to England.

The English were well pleased with this offer. They might not be able to simply expel the Brazilians from a given area of land, but there was so much land that there would not be a need. They agreed.

For the aristocracy of the Empire, this was too much to bear. They had suffered under the Emperors’ slow centralization of power, they had been taxed, they had seen merchants be given more and more rights, their requests to the Emperor had been ignored for decades, and now territory was just given away? This was intolerable! It would not stand!

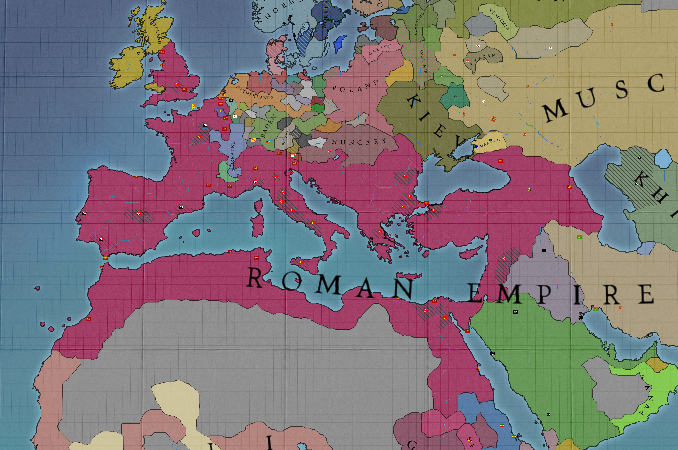

The revolt was sudden and severe. The revolutionaries raised the Empire’s flag over their one million troops1 as a sign of opposition, the Emperor’s flag being much more well known for centuries. The most significant cities were immediately under their control, the only exceptions being ones hosting various legions.

Konstantinos’ reply was just as strong. He declared himself the absolute ruler of the whole Empire. Justice would be by his agents, taxation by his agents, all administrative work by his agents. Nobles would not be allowed to field their own armies. Nobles would no longer be much more than significant landholders. Of course, this would be a legal fiction of sorts, just as the nobles’ former rights of justice, taxation, and administration in their lands had been a fiction. Imperial agents had long been assigned to the different provinces and directed the power of Constantinople into local affairs. Once the revolt was ended, local powers would soon be at work directing the local powers to their own ends. But the legal framework had now been set.

Gallia was defended by II Legio, XIX Legio, XXI Legio, and XXI Legio as a result of the religious wars in the Germanies. The rebels there did not last long.

Lombardia was defended by VII Legio, XIV Legio, XVI Legio, XVIII Legio, and XX Legio, also placed due to the wars of religion.

Britannia was defended by IV Legio and XVII Legio, long resting after the wars with Scotland and England.

Iberia, Egypt, Syria, and the Imperial heartland were undefended as the revolt began.

The Lombardian campaign slowly pushed their opponents south, towards the morass of revolutionaries along the peninsula.

The Gallian campaign defeated the rebel armies, but found that an army of Norman patriots had traveled to try to carve out an independent nation.

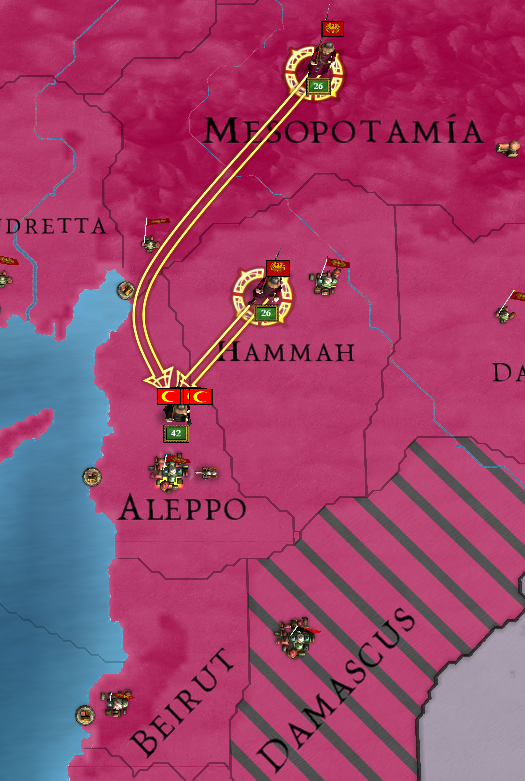

In Syria, I Legio and IX Legio made their move.

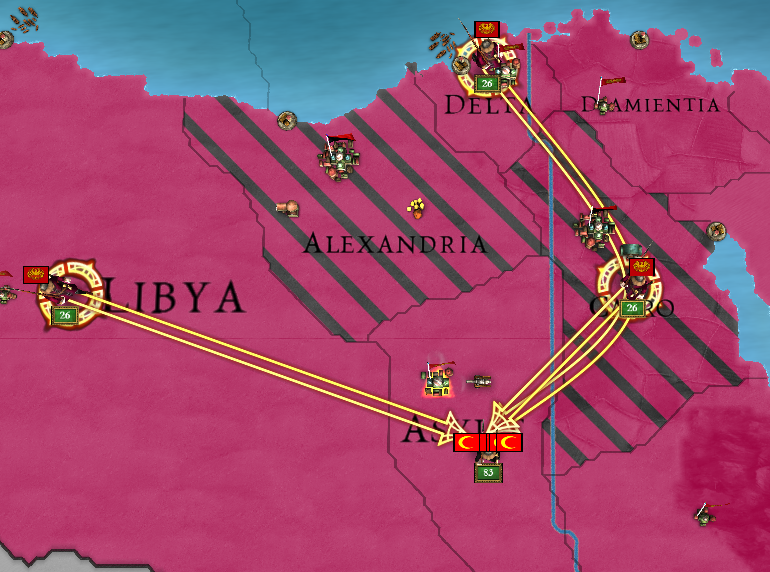

In Egypt III Legio, X Legio, and XV Legio did the same.

The Britannian campaign subsided to a siege of Oxford by XVII Legio, while IV Legio shipped off for Iberia.

The opening move of the Syrian campaign was a resounding defeat.

Meanwhile, three legions made a bold stroke into central Italy while two sought to bring Liguria and Mantua back under control.

As the Egyptian and Syrian campaigns diminished to sieges, III Legio and IX Legio were transported to Anatolia to attempt to bring matters under control there.

In turn, IV Legio, XXI Legio, and XXII Legio began their work in Iberia.

When the rebels on the Italian peninsula inexplicably began to move south, the Legion took advantage of the opportunity to push the boundaries of the war.

The war continued everywhere, but slowly tightening for the rebels. In Iberia, XXI Legio got too eager for battle, racing ahead of their IV Legio and XXII Legio. Their eagerness saw them all captured at Lisboa. The complete capture of the celebrating rebels in Lisboa two days later was scarce comfort, as too few soldiers could be found to reform the lost legion.

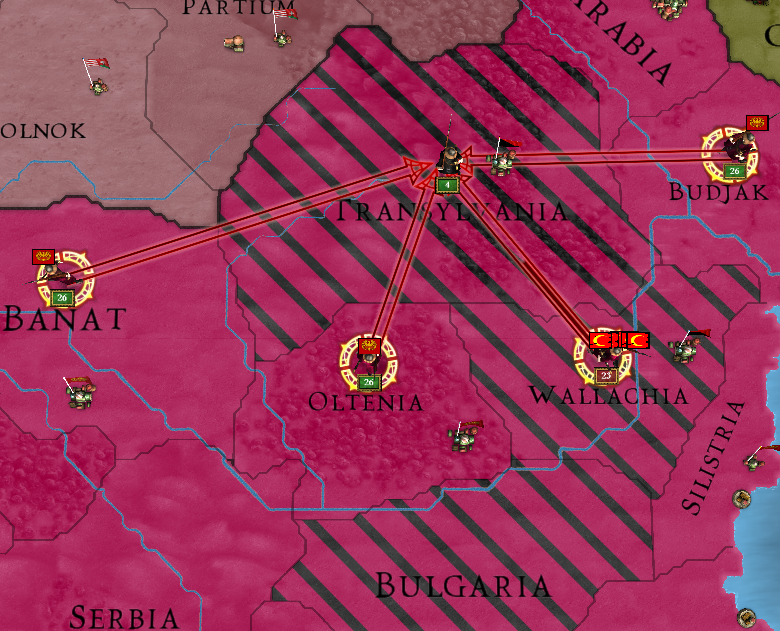

The rebels in Dacia were more clever than most. When four legions moved to attack them, the rebels quickly moved to attack one first, before the others could change their course. Thanks to Pavlos Diasorenos’ clever tactics, III Legio was able to withstand a force twice their number. The legions all moved to intercept the rebels in Transylvania.

By 1629, only the Sicilian and Greek regions had rebel troops remaining. The legions continued to press forward.

VIII Legio was lost as the Sicilian campaign moved to the island of Sicily. And then III Legio was lost in the Greek campaign.

But the legions continued to press the rebel armies, and finally in June of 1630 no rebel armies remained. Only the city of Palermo resisted the Konstantinos’ will, and VII Legio had brought them to desperation by siege. They held out until September.

The revolt had lasted four and a half years. A short time from a historical perspective. But a long time to live through. And for the estimated one million Imperial soldiers lost in battle or the uncounted numbers of the rebel forces, it was far too short a time to live and to die.2 But now the peoples of the Empire could begin to rebuild what had been lost.