The Empire Strikes Back 64 - The Fall of the Papacy

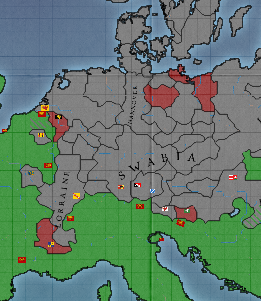

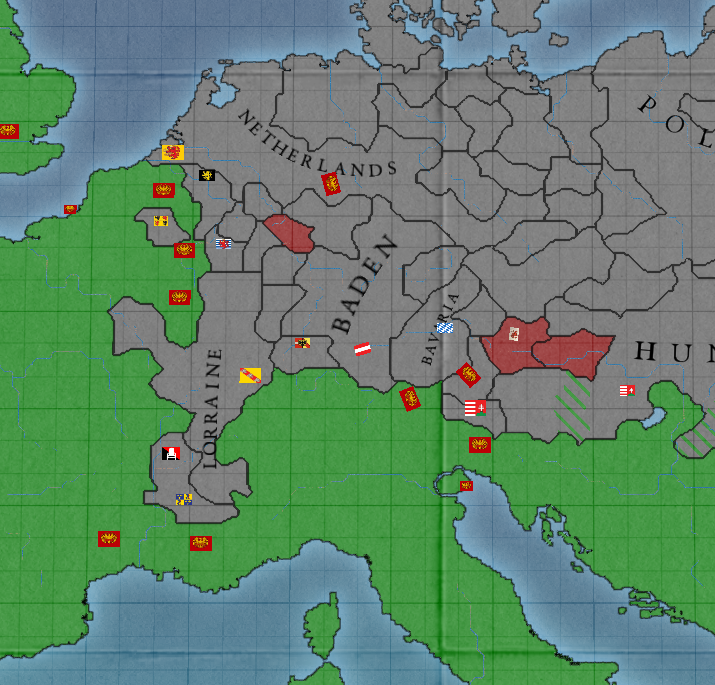

Konstantinos began the 17th century by continuing the wars of religion. On the 20th of February, 1600, he declared war on Styria. Their allies joined them, of course, though converting them to Orthodoxy before the war would have been a better defense.

In the midst of this war, a colony was founded in Banten, on the island of Java. Konstantinos commissioned the Imperial East India company to transport and sell the spices that would surely be flowing from this colony.

Styria agreed to a peace after IV. Legio stormed and captured Kärnten. Their other allies took a little longer to agree to a white peace.

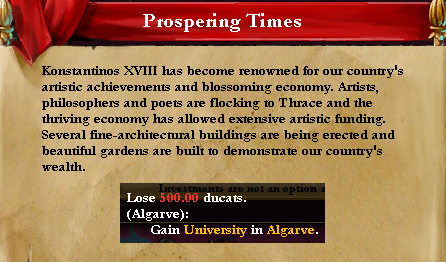

Despite the near-constant wars, so many artists, philosophers, and poets were in Thrace that it was becoming hard to find new patrons. Konstantinos gave the more adventurous ones the funds to start a new university in Algarve. In the coming years, many more groups would request funds to start new universities. Konstantinos funded the ones that picked more practical locations.

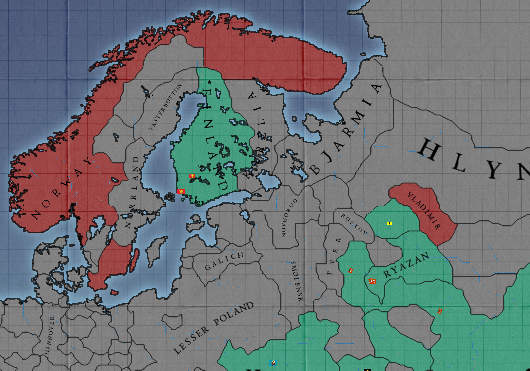

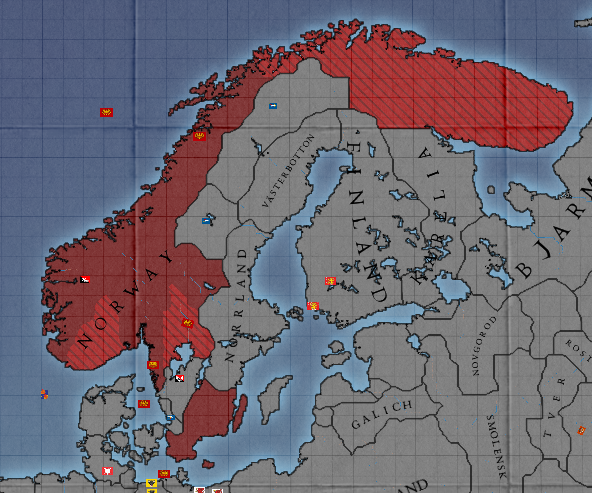

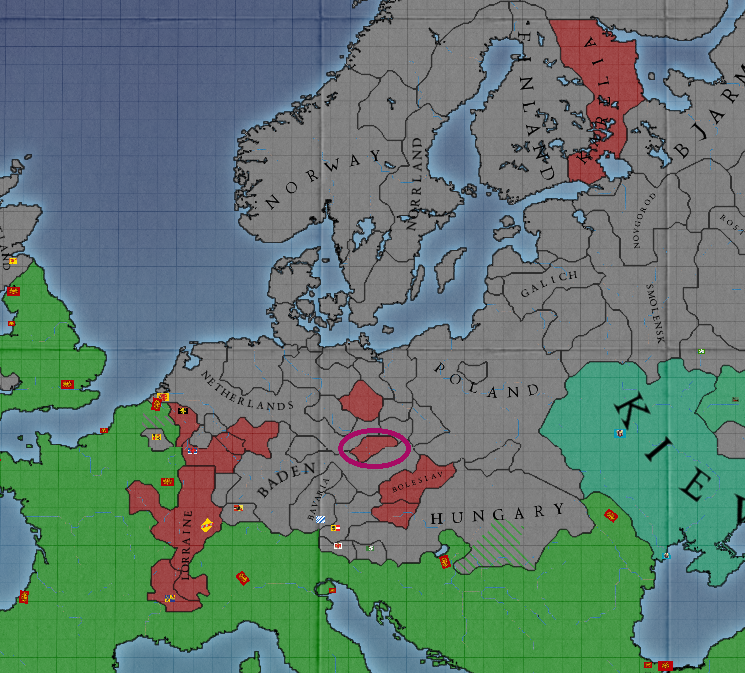

While XIX. Legio marched east to help Khiva in a war against Tibet, Konstantinos declared war on the largest Protestant nation in existence: Norway.

Displaying a lack of sensibility to the Emperor’s desires, the members of Vouli took the time during the war to request that Konstantinos provide an opposition to the English colonies in North America with a new Imperial colony. He remained focused on the war. Despite being outnumbered, XI. Legio attacked the Norwegian army.

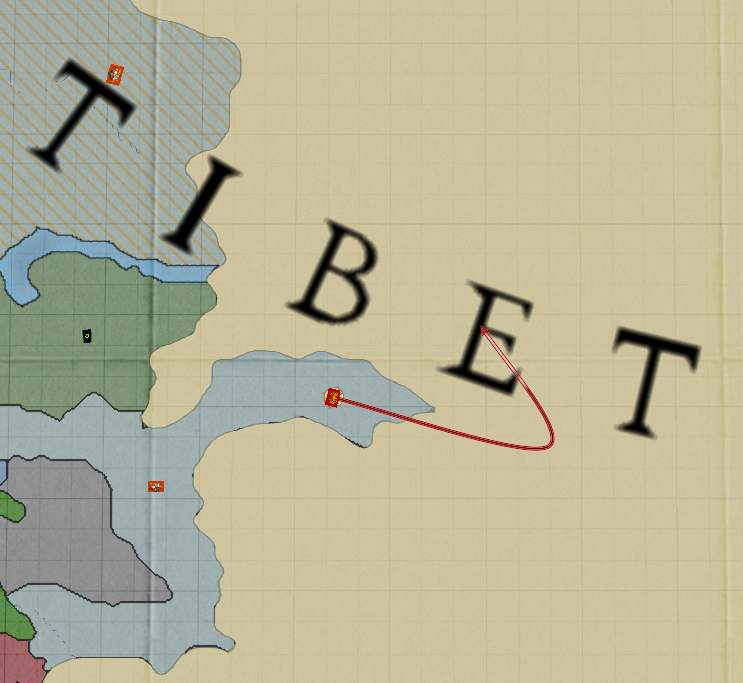

Meanwhile, XIX. Legio explored the Tibetan lands, hoping they did not run into any Manchu armies (Manchu having joined the war in the east in Tibet’s defense).

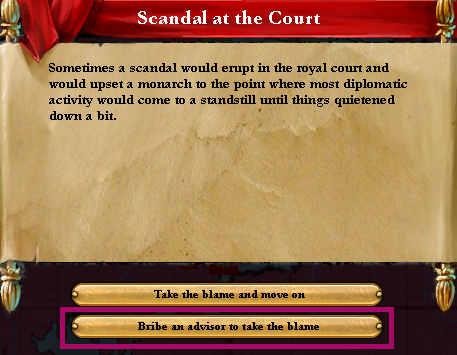

When the Delaware colony failed, accusations flew. Many claimed that Konstantinos let it fail on purpose. As evidence, they pointed out his lack of effort to colonize North America at all. Before matters got too out of hand, Konstantinos was able to produce the ministers whose ineptitude had allowed the colony to fail. That he had bribed them to confess remained a secret for now.

Vouli decided a North American colony was not worth the effort, and instead asked Konstantinos to recover an Imperial province in Hungary. Again, Konstantinos ignored the request.

Meanwhile, by the end of 1602, Norway had agreed to become Orthodox again.

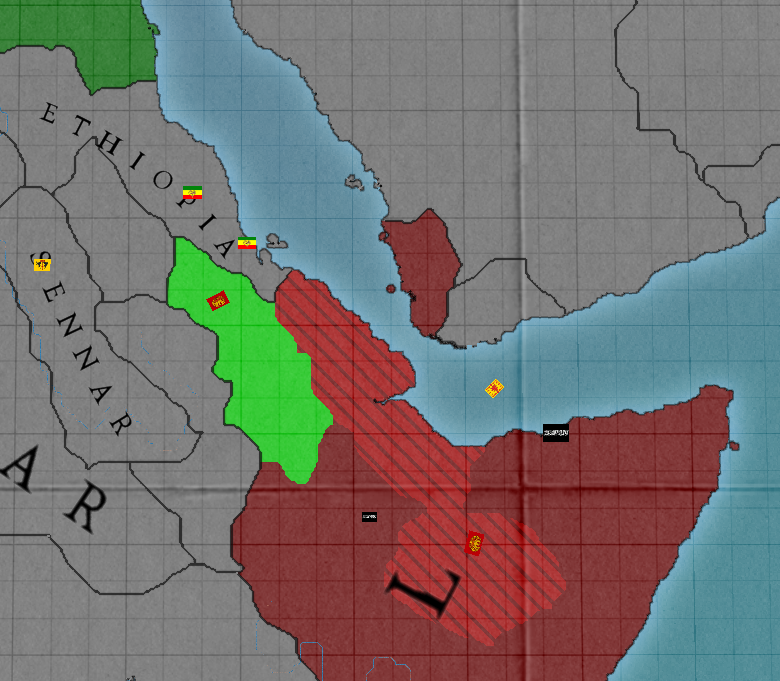

The following war against an inconsequential Baltic power drew in Adal. It took time for three legions to march to eastern Africa, but in March of 1605 XII, XIV, and XX Legio forced Adal to give territory to Ethiopia.

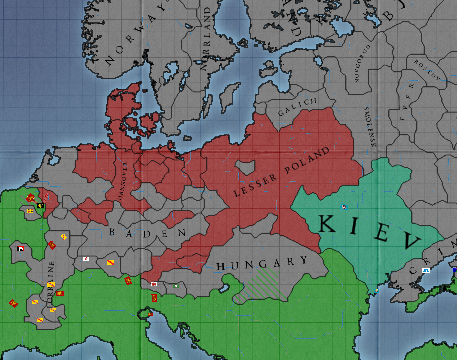

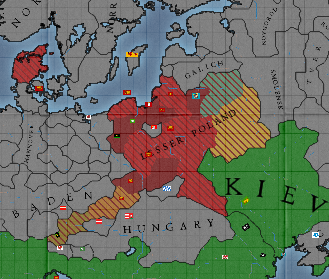

At the beginning of 1606, the Empire again went to war, this time against Meckelemburg, a Catholic nation. Most of the northern German nations rose to its defense and Lesser Poland eagerly joined the war.

Before 1607, all but Lesser Poland had been forced to the negotiating table. For Lesser Poland’s efforts, they were stripped of their outer territories in September of 1608. As recompense, Konstantinos would later declare them the Kingdom of Poland, no longer the Lesser.

While the nations freed were initially exuberant, they grew worried when the Empire broke all treaties with them. They may have been relieved when there was no immediate attack. Unbeknownst to them, this was because Konstantinos had received word of the powerful effect of artillery in war, and was taking the time to ensure the legions were equipped with plenty.

Meanwhile, the Empire had developed closer ties with the Cherokee. They were suffering from a terrible plague. When they requested aid, Konstantinos sent healers, led by the most compassionate priests he could find. It was little wonder when the Cherokee leaders turned to the true faith, again demonstrating that a pagan was merely waiting to hear of Christ (a belief dating to the Il-Khanate’s and Golden Horde’s wholesale conversions centuries before).

After just a year of peace had passed, the Empire began wars against the newly freed nations, also forcing them to Orthodox practice. They would have fallen easily, but for their allies. Those allies were punished: broken up, humiliated, or even absorbed. The absorbed ones were given in pieces to friendly states, unlikely to arise again.

As this war finished, the Inca sent word, asking for healers and missionaries to be sent to them. There had apparently been good word from the Cherokee.

It was 1615 before the Imperial diplomats had specified all the border changes from the last war. Once that was done, Konstantinos declared a war on the last nation supporting the Reformed church. Many allies defended them, as always, and many allies fell, as always.

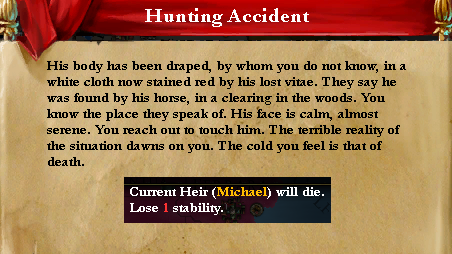

Shortly thereafter, Reformed zealots — believing they had nothing to lose — attacked Michael Doukas while he was hunting. They killed him, mutilating his body, and leaving it prominently displayed. The shock of their actions reverberated throughout the Empire. Konstantinos was even more convinced he must remove all heresy.

Just before 1620, the last political support for Protestantism was removed, though Protestant communities remained in Köblenz and Slesvig.

Early the next year he began one of the last wars against the Papists.

The Inca had been most impressed by the Imperial customs mentioned by the priests that had traveled to help. An exchange of diplomats a nobles began between them and the Empire.

The next Papist war brought a resurgent Golden Horde to the fight against the Empire. The Golden Horde was broken apart again and forced to concede again that they were no longer a significant power in the world.

The penultimate war against the Papists was a minor thing.

During the war, the Cherokee recovered enough from their religious confusion to take a hint from the Inca and request closer Imperial ties.

Finally, in December of 1625, Emperor Konstantinos began the final war against the Papacy. No-one came to the Pope’s defense, and he himself was trapped be rebels who controlled his small territory. XXI. Legio found an army from the Netherlands at the gate and helped them gain entry. The Pope was forced to surrender his lands to the Dutch, and would after that point wander between the few Catholic enclaves not yet stamped out by their rulers.

Konstantinos commissioned a monument to mark this final victory. And then he made a decision whose ramifications were unprecedented since the time of Diocletian.