The Empire Strikes Back 30 - East and West

During the truces with European rulers, Konstantinos had waged a campaign against Egypt, waging war against vassals who had rebelled against the Egyptian king. He eventually conquered enough that he could usurp the kingdom, and once he had granted it to one of the new vassals he had set in place, everyone was willing to swear fealty.

The Egyptian campaign won, he began a campaign against Jerusalem. This one would likely take longer, as the vassals of the king displayed no rebellious tendencies.

When his truce with the Germans expired, he immediately fought a war for the duchy of Susa.

That complete, he turned his gaze west.

This was Toulouse. Of old it was an Imperial territory, though it was later overrun by barbarians of all stripes. After being conquered by the Franks, it was made part of the duchy of Aquitaine. After years of Frankish infighting, the Carolingian Franks reconquered it, and Charlemagne organized it as part of the kingdom of Aquitaine. While the Frankish authority faded, leaving the Capet dynasty merely kings of France, Toulouse still swore allegiance to them. It stayed loyal through civil wars, Muslim invasions, everything (though some of the coast fell under English rule in the early 13th century). Finally, in 1310, Konstantinos declared war on France to regain it for the Empire.

It was one of the riskier wars fought by the Empire in quite awhile. The King of France sent a massive army (nearly as large as the collected forces of the Emperor) to break the initial sieges. The Scholai Palatinae gathered in order to withstand this army, the last ten thousand arriving by boat after the battle had begun. The gathered Scholai Palatinae were able to smash the French forces in what was a decisive battle, and the rest of the war was just sieging and winning foregone battles.

After the king of France surrendered, Konstantinos again tried to take advantage of the duke of Provence rebelling against his liege in order to declare a war on the duke for the duchy.

During this war it was discovered that Gerasimos of Perre, the King of Croatia, was trying to fabricate a claim on the Empire. Furious, Konstantinos sent men to arrest him. But Gerasimos escaped and began a rebellion.

Unfortunately for him, 27000 of the Scholai Palatinae were idly sitting out the war for Provence. They were sent by sea to Croatia, where they quickly put down the rebellion.

Both wars won, Konstantinos again looked to the western sea. He noticed that the old king of France, the one to whom he had a truce, had died…

This was Iberia. Long a territory of the Empire, it had fallen to wave after wave of barbarian invasion. Eventually, it was overrun by Muslims, with just a small Christian foothold in the north remaining. But the christian kingdoms pushed back, regaining most of northern Iberia by 1066. From then on, there was a constantly shifting series of wars and alliances among Christian and Muslim kingdoms. A few times, it looked as if the Muslims would control the entire peninsula. In the late 12th century, an eastern Iberian Muslim kingdom even conquered much of Aquitania from France, though two Christian kingdoms held the western half on Iberia at that time. Those Christian kingdoms fought and critically weakened the Muslim kingdom, but themselves fell to civil war, which allowed other Muslims to conquer much of the Christian lands. In the latter half of the 13th century, France had its revenge, pouring over the Pyrenees and conquering a significant amount of north-eastern Iberia. The christian Kingdom of Leon slowly regained power, and by the time that Konstantinos declared war on the powers in Iberia (France; Seville, during a rebellion from Leon; Leon itself; and the Almoravid Sultanate) for the Mediterranean coast, Leon held the majority of the peninsula. France held the lands north of the Ebro, as well as the duchy of Galacia in the northwest, and inconsequential Muslim kingdoms held the remaining territory.

By the time those wars were complete, Konstantinos’ truce with Jerusalem had expired.

After the war for Ascalon was complete, he was again able to usurp the kingdom, and the duck of Oltrejourdain agreed to swear fealty to Konstantinos. The duke of Jerusalem (formerly the king) would not so agree.

With the Jerusalem campaign again waiting for a truce to end, Konstantinos fought a series of minor wars whenever a truce expired. Though he waged fewer than expected.

When two simultaneous civil wars broke out in France, the opportunity was to great to miss. Konstantinos, an honest man, was unsure, but his wife, heir, and advisors were proud, and longed to see the Empire restored to its full glory. He yielded to their pressure, and began declaring war on the various rebels.

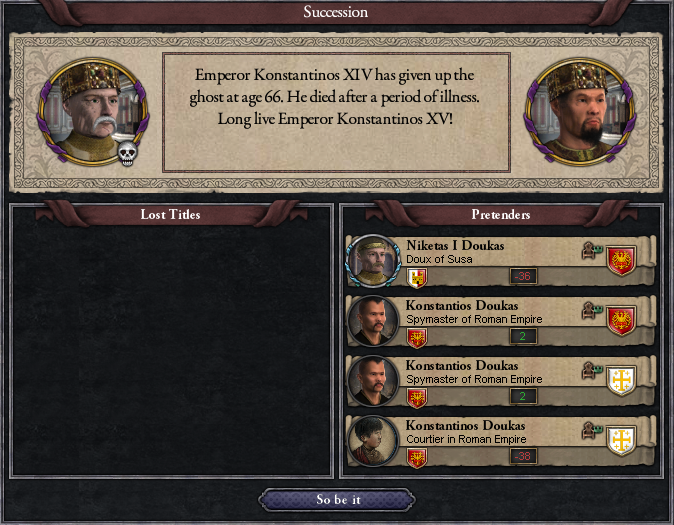

The wars were successful, but before the last of them was fully concluded, Konstantinos XIV died, succeeded by his oldest son, Konstantinos XV.