The Empire Strikes Back 23 - The Donation of Constantine

Konstantinos had reclaimed the whole of the Empire. It was enough to fulfill any man’s pride, even his. But now his advisors had sent a scholar to him. They claimed this scholar had news of great import, but that he tended to speak long. Konstantinos steeled himself.

“My liege, as you will recall, the Empire is of great age. It had had a great many civil wars, even discounting those during the era in which is was a republic. It was these civil wars which led to the division into East and West Empires.”

“Yes, yes, and the West fell to barbarians. Now only the East remains, therefore we are simply the Empire.”

“Quite true, my liege. But there are some who claim that via translatio imperii, they are the successors of the West Empire. They style themselves the Holy Roman Empire.”

“Fah! Germans! They are none of those three. All civilized men know it!”

“Agreed, your majesty. Those within the Empire know the folly of those that claim to compare. But many outside the Empire ascribe to their views. After all, the former Patriarch of Rome, the Pope, supposedly granted the West Empire to the Germans, having inherited it from the Donation of Constantine.”

“A document that is surely a forgery!”

“My liege, that is why am here today. I have evidences that could prove that it is false, to the satisfaction of all, both within the Empire and without. But I need access to more records, stored in the archives of the Duchy of Genoa.”

“Proved false? That would be…hmm… You shall have access to all my archives in Genoa.”

“My liege, I fear I shall also need access to archives in Nice, still held by the French.”

“Very well, scholar. You shall have access to the archives in Nice.”

When the war had been won, Konstantinos spent some time letting the Scholai Palatinae recover their strength. Eventually, Konstantinos demanded a report from the scholar.

“My liege, I have found several sets of correspondences mentioning the false Donation. With the letters written by the other members of these relationships, I could know the name of the forger and where he lived.”

“And where would these letters be?”

“In Tunis, my Lord.”

“Where in Tunis?”

“All over the duchy, I am afraid.”

“Hrmph. Prepare your desert clothing, scholar.”

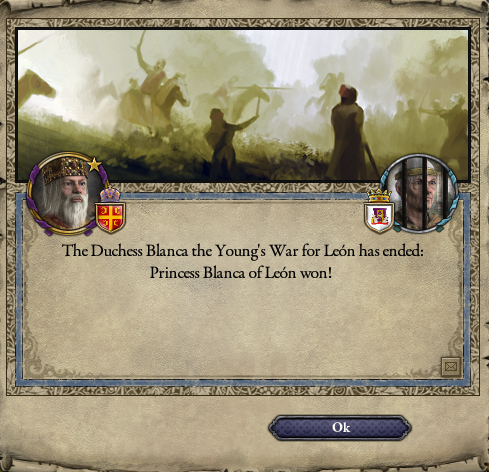

The war for Tunis was swiftly won, but a few baronies were pledged to other local rulers. Two more short wars were fought for them. During the latter, Konstaninos received a request for aid from his daughter in law, the Duchess of Leon. He had married his heir to her when she was Queen of Leon, and apparently she had lost the title at some point. But now she was warring to reclaim it. Konsantinos sent the Scholai Palatinae and many levies. But the King of Leon did not submit easily. After over two years the war was finally won.

As the troops were being shipped home, the scholar met Konstantinos on the fleet.

“Have you a name scholar?”

“Yes, my Lord. And not just a name, but an exact house where he lived. And it’s known kept his records there.”

“Excellent! Where is it?”

“Venice.”

“Hahaha! Scholar, you have given me excuses to entirely take control the trade of the Sea. To Venice!”

The city of Venice fell swiftly. The Scholai Palatinae could barely be restrained from sacking every bit of the city that had destroyed the former retinues of the Empire. But the house with the records was kept safe.

“My liege, I have it! The complete tale of how the Donation of Constantine was forged. I have written a report, with extensive references, for you.”

“Advisers! Have you examined this report?” demanded Konstaninos. When they confirmed that they had, and it was accurate and unassailable (if boring), he continued. “Have copies made and sent throughout the lands of the West Empire.”

And then he smiled sardonically. “And send copies to the Germans. And the Pope.”

He turned back to the scholar. “Well done, scholar. For this, you shall be greatly rewarded. What is your name?”

“Kaisarios, my Lord.”

“Well then. Doge Kaisarios of Venice, your name will be forever remembered within the Empire!”

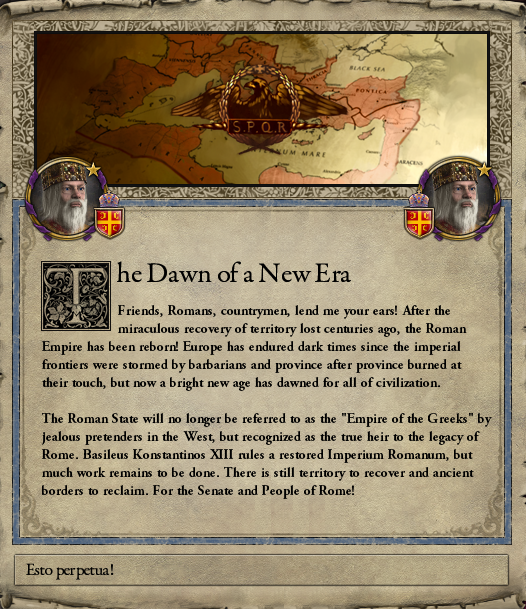

And in late 1233, the report was sent throughout the land. It made little practical difference in most locations that had long been lost to barbarians. But all now recognized the Empire as the Empire, and not just the empire of the Greeks.

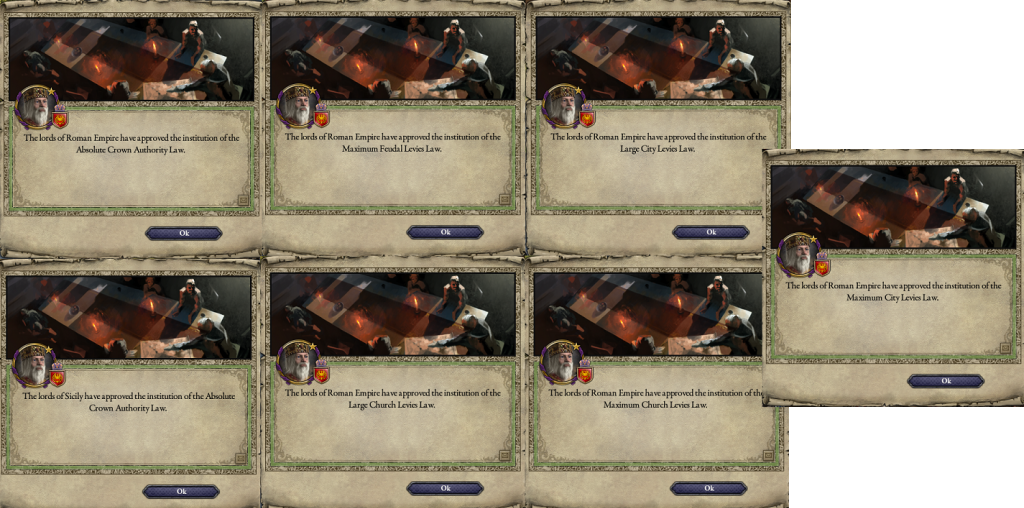

Having fulfilled all that his ambition and pride could desire, Konstantinos spent the rest of his days improving his demesne, tightening his control of the Empire, and receiving reports of the ravages of the Mongols.

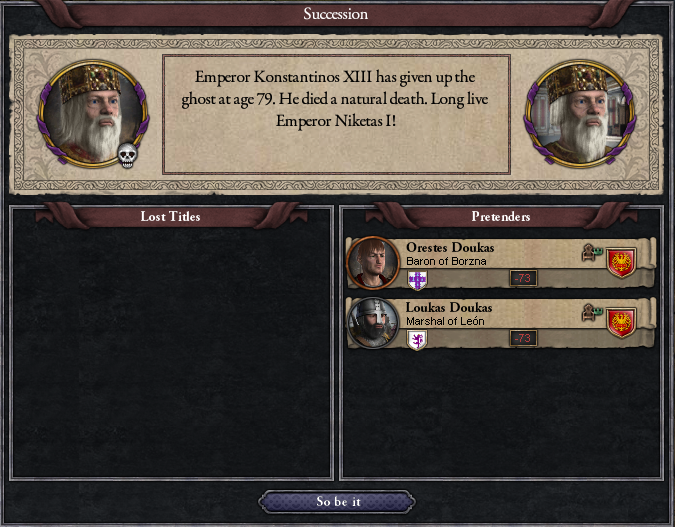

Finally, on the ninth of May, 1260, he died of old age. He was succeeded by his third (and only living) son, Niketas.