The Empire Strikes Back 60 - The Holy

Before launching the war for Portugal, Konstantios took advantage of his steadily improving government to convince people to found new colonies.

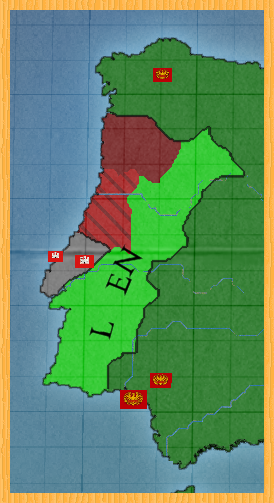

Despite having a great many powerful allies, León faced the Empire alone. Before the end of the year, they had been completely defeated. They were forced to give up their eastern provinces in exchange for peace.

During the war, Konstantios’ third son Markos got into a fight with his father. Konstantios wished Marcos to help govern one of the colonies, but Markos wished to work as an artist. Konstantios threatened to disown him, and Markos left Constantinople during the night. Konstantios mourned the loss, and was distressed that the fight had been so disruptive to relationships in the Empire.

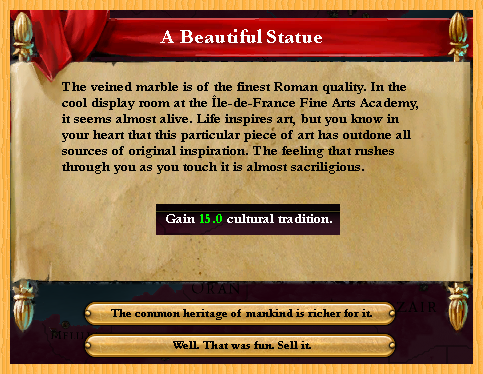

Months later, Konstantios had word of Markos in Île-de-France. He traveled there himself to reconcile himself to his son. When he arrived at the art academy, he found Markos had created a magnificent statue, the likes of which had not been created for over a thousand years. Father and son were reconciled, and Konstantios’ praise inspired others to excel where they might.

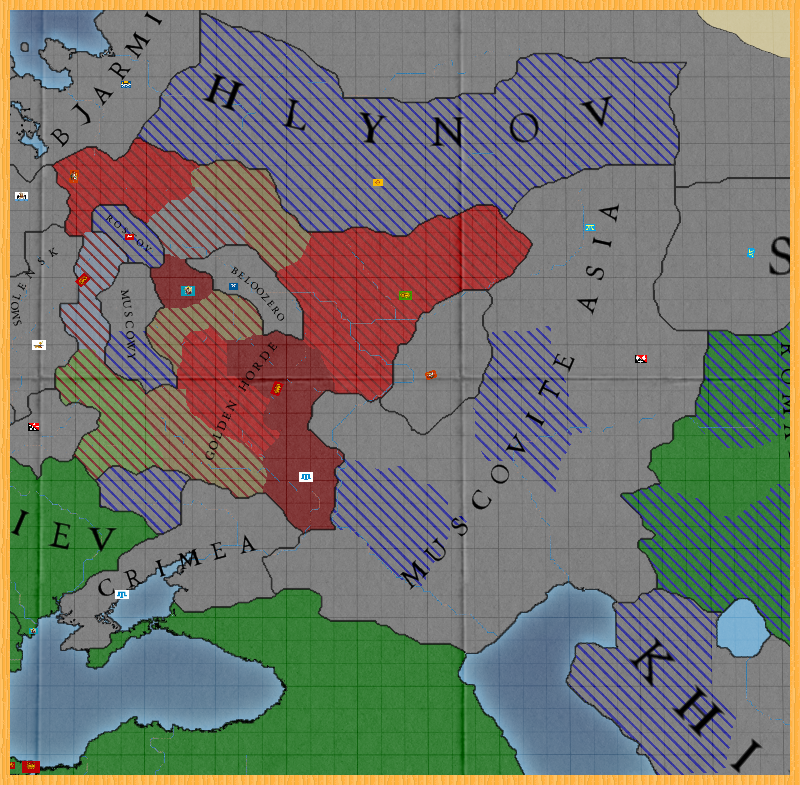

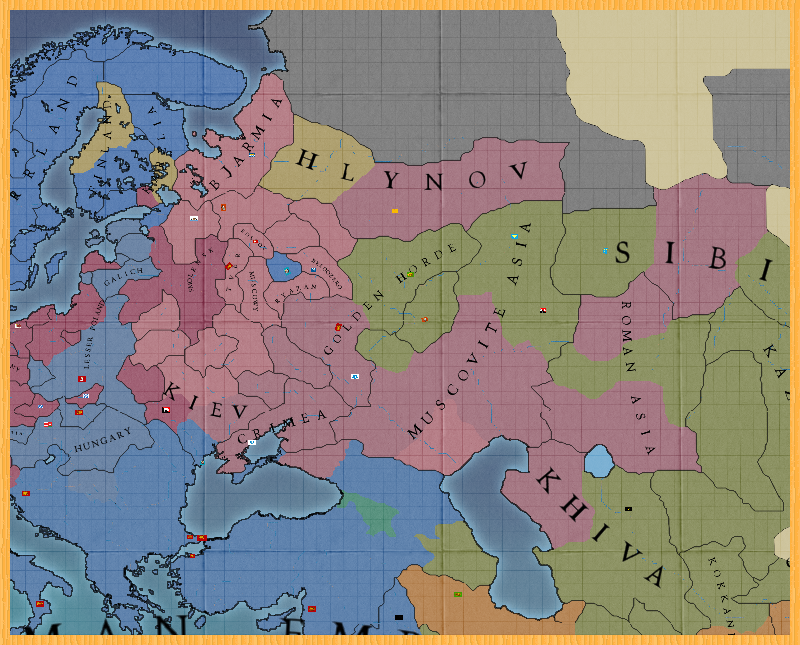

Konstantios had not changed too much, though. He declared war on the Golden Horde, ostensibly to help his allies, but really to continue punishing them for claiming to be an Empire. While their armies were no match for the Legions, their large wooded territory took a long time to occupy. But they were defeated, and forced to release most of their lands, and give up nearly all of their claims to far away lands they once owned.

With this defeat, the Golden Horde’s cultural hegemony over much of Europe and Asia was broken. Where once many had striven to emphasize the parts of their culture most similar to the Golden Horde, now they strove to emphasize the parts that were different. Even in the lands they still held, the people distinguished themselves from their leaders.

After this war, Konstantios sought to make founding colonies even more promising: the first thousand people to found a new city would be granted titles of nobility to go with the lands they claimed in the area.

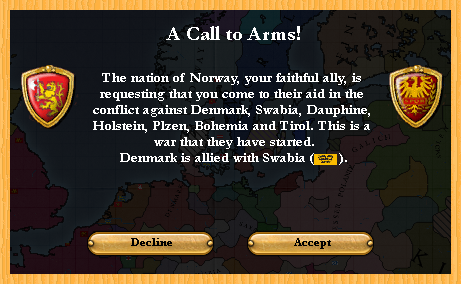

Before Konstantios could resume efforts in Portugal, Norway again asked for assistance. This time in a war of aggression against Denmark. Konstantios was pleased to see Denmark taken down yet further, so he agreed to help.

The Legions did the bulk of the fighting, but there was nothing to negotiate for that the Empire wanted. One by one Denmark’s allies were removed from the war. Finally, Norway forced them to surrender. Most impressive was how Norway forced Denmark to release Holstein, as Norway had conquered Holstein in the war. The small nation moved south as a result of the war, to Norway’s benefit and Denmark’s loss.

While that war was being fought, Konstantios began another war against Castelo Branco. Castelo Branco had pounced upon the weakened León and completely conquered them. This opportunism might have served them well, if they had not been in lands the Empire sought to recover.

They fell within a year, and while they were yet too strong to completely absorb, they were left destitute.

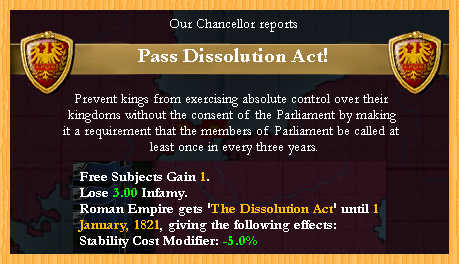

Now, the Empire was governed by administrators assigned by the Emperor. But during the middle ages, local nobles had gained much power, until the Empire could be compared to the feudal kingdoms of the rest of Europe. These nobles would often petition the Emperor when they had a specific desire, and it was a reality that the ones nearer to Constantinople had the ability to petition the Emperor more. Konstantios felt overwhelmed and distracted by these requests, so he streamlined the process. He would assign a regional Kyvernítis (governor) to handle local needs. For petitions that could not be addressed by the Kyvernítis, the nobles could pick a representative who would meet at a regular Oloméleia tis Boules (Session of Parliament) in Constantinople. Konstatios promised to call a Oloméleia at least once every three years, and if he did not, he would sacrifice the tax income owed to Constantinople. 1562 was truly a monumental year for the Empire.

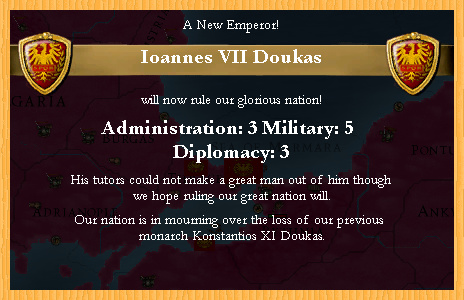

Three years later, Konstantios XI died in bed. He would be known as ‘The Holy’ for his efforts in protecting the faith. On 17 December 1565, Ioannes VII took the throne.

Theodoros, his much more skilled younger brother, was declared Heir the same day.