The Empire Strikes Back 48 - The End of an Era

By January 1433, Konstantios was ready for a campaign in the Alps. He began by declaring war on Upper Burgundy for Schwyz. The usual assortment joined in defense.

The Empire fought in Wales, in the Netherlands, in Smolensk, and in the Alps. Denmark’s alpine provinces were captured, and Konstantios took advantage of the opportunity to take control of the ones in Helvetia.

As other belligerents fell, the Swiss in Zurich revolted from Austria, forming an independent duchy. Konstantios was pleased to have an easier war ahead.

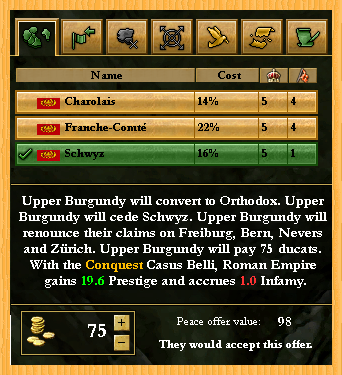

In March of 1436, the fortress of Schwyz fell after a long and bitter three year siege. Upper Burgundy had long been clamoring for peace, and now it was given them.

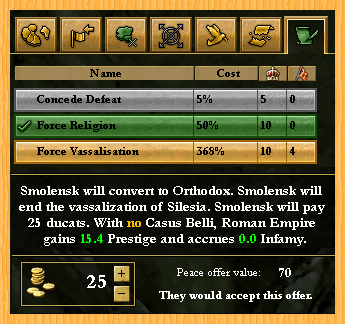

With nothing more to fight for in this war, Konstantios made peace with Smolensk, in such a way that the Pope would be further weakened.

By October, he was again prepared for war.

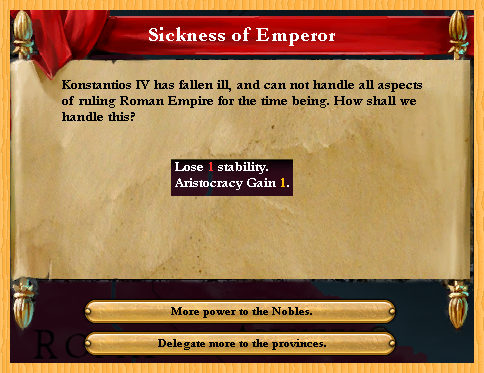

The constant wars had not allowed Konstantios to focus on ruling the Empire. The aristocrats took advantage of the opportunity to ensure that family influence was important for securing a position in the growing Imperial Bureaucracy.

The war was initially fought in northern Italy and in Croatia. But the Themas swept away all attackers. Bavaria inexplicably offered a white peace before they saw much action. Denmark soon followed suit. And while Hungary did not offer a peace, they accepted one.

In August, Konstantios finally held a coming of age party for his son. The party was the talk of Christendom, all other courts emulating the clothing, the dances, the foods in the feast.

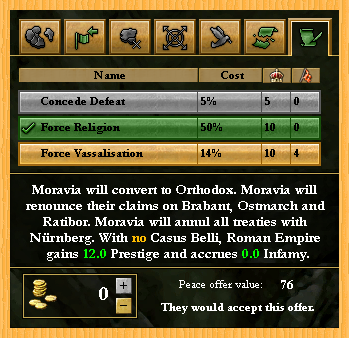

During the party, Konstantios declared that he would give Moravia a gentle peace. Surely they did not consider it gentle, but they remained independent. Of course, it was not Konstantios being magnanimous, but him recognizing that his reputation was becoming quite dark. Annexing Moravia was sure to stir up too much trouble.

Schwyz was not so fortunate. It was a vassal of Bavaria, and Konstantios knew it would be a great deal of trouble to start a new war with a better casus belli.

In February 1438, Bern fell to Thema Lombardia, and Nürnburg was annexed.

Konstantios forced a few minor states to convert to orthodox Christianity before he accepted a peace from Greater Poland. The war was finished.

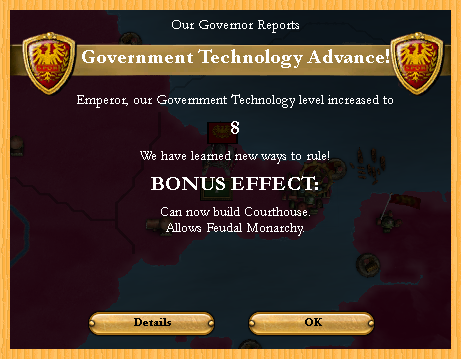

In 1440, there had been enough graduates from Imperial universities that Konstantios could start establishing secular courthouses throughout the Empire. Control of legal matters could be slowly wrested away from the church and local nobles.

While Konstantios prepared for the next war, Prince Konstantios went hunting. Though he was an expert horseman, he was found beside his horse, his neck broken. Again, the heir to the Empire had died before his time.

Konstantios suffered a deep grief at the loss of a third son. When he recovered, he was a much more cynical man, brimming with anger. He took this anger out on Tirol.

When St Gallen fell, Tirol was quick to surrender. But knowing there was a long truce with Moravia, Konstantios purposefully drug out the war, so to force many lesser states to stop worshiping the Pope.

While Konstantios took out his rage on those who would dare defend Tirol, his brother was able to convince the court to name a niece as heir. This was not ideal, but did ensure a Doukas would remain on the throne.

When the truce with Moravia was passed, Konstantios again attacked. Moravia was soon overcome, though the nations that came to its defense fought for much longer.

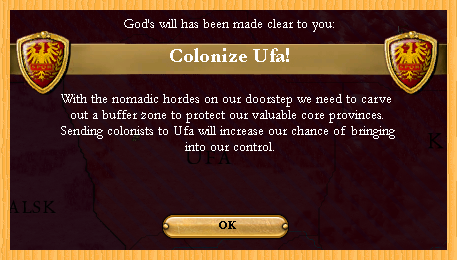

The brighter of the noble families saw the opportunity in becoming Imperial administrators. They pushed for the institution of Imperial administration in Timurid lands.

Meanwhile Konstantios felt that he had accomplished enough for one life. When he went to sleep, he never woke back up.